City officials cleared two Port Richmond encampments near Interstate 95 on Friday, where at least 20 people had been living along Allegheny and Westmoreland avenues.

The Office of Homeless Services (OHS) connected 10 people to services, while four declined assistance, according to city spokesperson Sherylle Linton Jones. The city declined to share details on the housing, treatment programs, or other services offered.

People living in the encampments estimated over 20 people were living there. The city declined to share its full count of people.

According to Jones, the action was part of an expedited encampment resolution. Jones said the city issued notice of the resolution on Nov. 4 and began offering service connections. City policy generally requires 30 days’ notice for people who have been living in an encampment for at least 30 days. But Jones said PennDOT deemed the areas as “hazardous,” which she said justifies an expedited sweep under the city’s resolution policy.

The city defines a hazardous encampment as one that “threatens the health and safety of the individuals residing therein and/or the individuals residing in and/or visiting the community where the encampment is located," according to its “encampment resolution” policy.

PennDOT has “jurisdiction” over the property, according to Jones. PennDOT spokesperson Robyn Briggs said the agency identified “combustible materials located at the site – under I-95 – which are at a higher risk of fire during the current dry weather conditions.”

“In light of our concerns about the potential fire risk, PennDOT reached out to the City, which led to relocations last week,” Briggs said.

Jones said the city’s reasoning for clearing the encampment was “to connect people living outdoors with, as needed, shelter, treatment or other homeless services.” She also said the combustible materials at the encampments posed health and safety risks to "not only residents, but to transportation infrastructure, PennDOT property and staff, and commuters.”

Kevin and Carolyn, who requested their last names be withheld for privacy reasons, said they had been living in the Allegheny Avenue encampment for about a year until they were ordered to move on Friday. By 11 a.m., they were pushing three shopping carts of their belongings on the street, hoping to find a shelter that would allow them to stay together as a couple.

Carolyn spoke with Project HOME staff for over 30 minutes as they called local shelters. No shelter could accommodate her and Kevin together, she said. She gave her phone number to a Project HOME staff member who said something might eventually open up.

Limited space for couples has been a barrier to accessing temporary housing according to advocates and unhoused people in Kensington.

Carolyn was evicted from her house just before the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) established an eviction moratorium in September 2020. Kevin, who served in Afghanistan from 2008 to 2012, said he started using drugs after he returned home due to high anxiety.

Outreach workers visited the encampment Thursday night and gave them duffel bags for their belongings but offered no shelter options, according to Kevin.

“No shelter or nothing,” he said.

John Spencer was one of at least six people sitting outside of the barricaded area after being displaced Friday. He was waiting under the I-95 overpass on Allegheny Avenue.

“It’s messed up what the mayor is doing to all of us,” Spencer said, adding that city officials are forcing them back into the neighborhood’s residential blocks, which he had been trying to avoid.

Both encampments had been set back from the sidewalks, hidden behind fences and shrubbery.

“The people that live in the houses, they don't want us there,” Spencer said. “They're basically putting us all out in the open… We got nowhere to go.”

Another man tried to retrieve his items that were stored at one of the encampments on Friday morning. He told Kensington Voice that his two backpacks were beyond the police barricades, but he was not allowed to enter the area to get his things.

Crystal, who currently lives at the shelter at 21st Street and Girard Avenue but had been using the encampment as refuge, said OHS staff woke her up early Friday morning to offer her help.

“They just asked, ‘What do you need? Whatever we need we can get you. What do you need us to do?’” said Crystal, who requested her last name be withheld for privacy reasons.

She said she feels like the city isn’t fully prepared to support the people they are displacing or moving into shelters. She added that people need easier access to medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD).

“I see what they’re trying to do, but they’re just not there yet,” Crystal said.

The city has operated the shelter at 21st and Girard in Fairmount since 2022, but recently expanded it to serve people with substance use disorder. Some Fairmount residents have been pushing back against the shelter, and Philadelphia City Council voted to prevent the city from extending its lease beyond 2025.

Friday’s encampment clearing follows an August sweep that displaced about 30 people who had also been living along I-95 in encampments closer to Girard Avenue.

A 2023 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association suggests that long-term health outcomes for people experiencing homelessness are worse when they are continuously involuntarily displaced compared to when they are not displaced at all.

David Peery, Executive Director of the Miami Coalition to Advance Racial Equity and co-author on the study, said homeless encampment sweeps compound unhoused peoples’ trauma and suffering and lead to increased hospitalizations, overdoses and deaths.

“Involuntary displacement of people experiencing homelessness may substantially increase drug-related morbidity and mortality,” the study says.

The researchers suggested connecting people to safe and affordable long-term housing and supportive services could mitigate those harms. One study author said solutions should include street medicine, medical outreach, substance use treatment, and harm reduction services.

The National Homelessness Law Center (NHLC) claimed the August sweep was unconstitutional, partly because it violated the city’s encampment resolution policy. Some people said they had been living in the encampment for years, and were given six days notice to leave, instead of the required 30 days.

The city’s encampment policy outlines procedures for clearing encampments, including the “disposal or storage” of personal items removed and “outreach and engagement of individuals to ensure connections to services.”

According to the policy, the city is required to “offer alternative locations for individuals or identify available housing for encampment occupants” and to store personal belongings for a minimum of 30 days.

The city declined to share how many peoples’ belongings were placed in storage during Friday’s cleanup. Kensington Voice witnessed one person placing their items in a bin with Encampment Resolution Team (ERT) staff.

Encampment resolution flyers were posted on Nov. 8, according to a flyer at the scene, though some people said they saw flyers posted on Tuesday night.

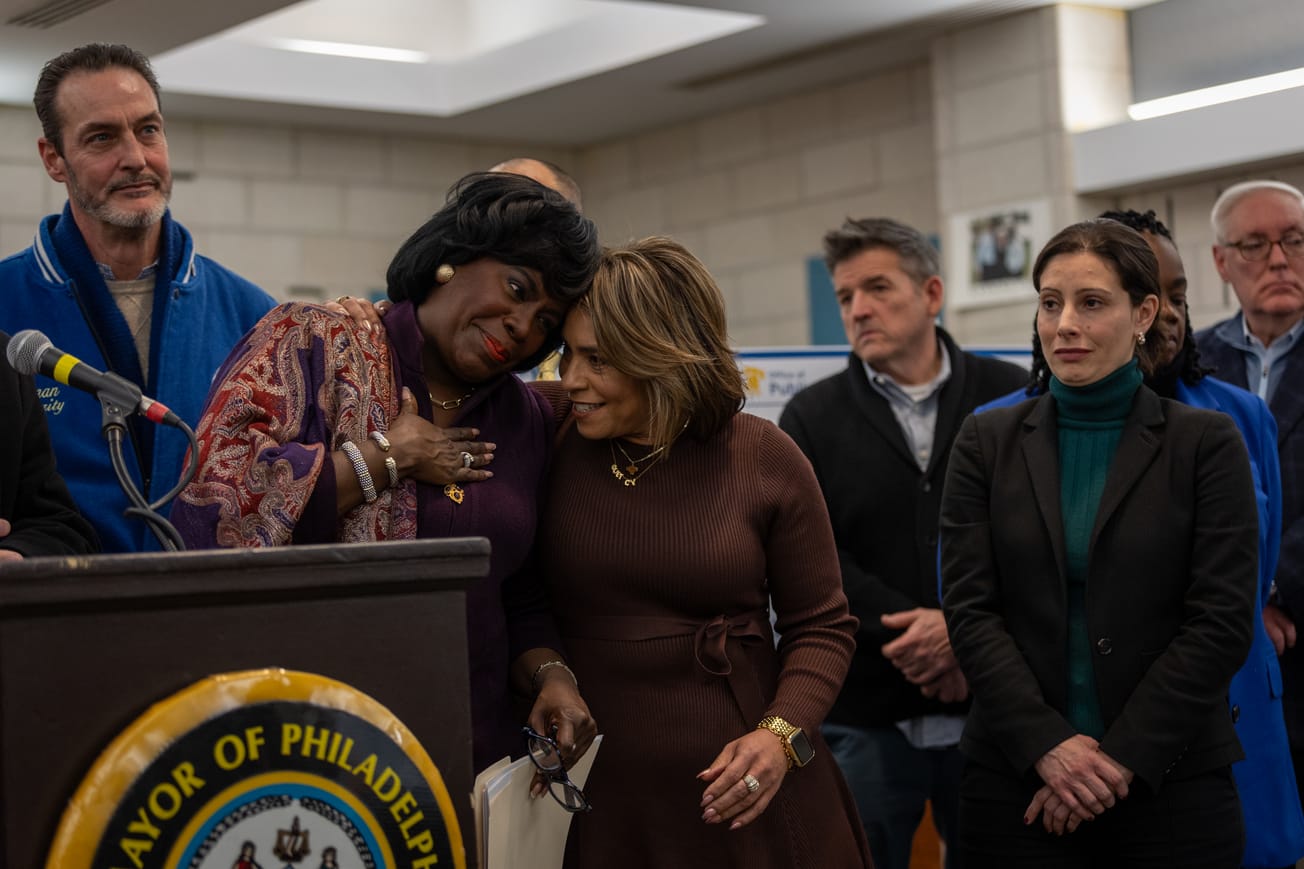

Multiple city leaders and staff were on site during the clearing, including Chief Public Safety Director Adam Geer, Deputy Police Commissioner Pedro Rosario, 24th District Police Captain Christopher Bullick, Neftali Ramos, the Kensington coordinator for Mayor Cherelle Parker’s office, and Marnie Aument-Loughrey, who works under Ramos.

The city’s Encampment Resolution Team (ERT), staff from One Day at a Time (ODAAT) and Project HOME, and police officers from the East Division Service Detail were also there.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.