This story is part of our “Hey, City Hall! It’s us, Kensington” series. Do you have a question for Philly government? Our journalists are here to bring your questions to City Hall on your behalf. Just fill out this form, and we’ll get straight to work.

On March 15, the New Kensington Community Development Corporation (NKCDC) tweeted a thread of clarifications about the opioid settlement.

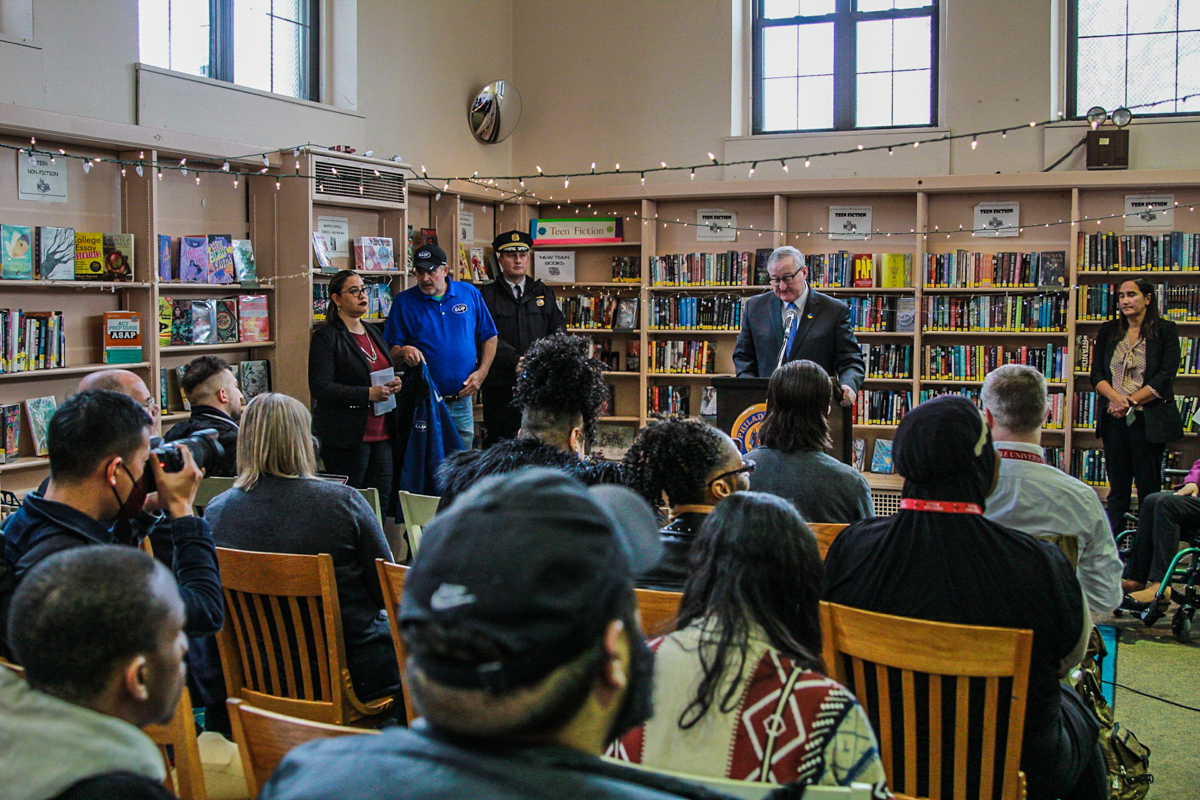

The clarifications came more than two months after a City press conference, where Philly officials announced the City would spend $7.5 million from the national opioid settlement on what they described as the “Kensington Health & Wellness Corridors master planning effort.”

“The planning framework at kensingtonplan.org represents a growing movement of community members and organizations, not a new city initiative,” the thread said. “While the City has said it will take cues from these planning efforts, it is not paying for the planning.”

According to Lowell Brown, the communications manager at NKCDC, the opioid settlement funds are not paying for Impact Services and NKCDC’s ongoing Health and Wellness Corridors projects or the new neighborhood planning process.

Instead, a majority of the settlement funds will go to housing initiatives like rental assistance and home repairs, Brown wrote in an email on March 3. For those housing initiatives, Brown said there will be an application process for homeowners and renters.

The leftover settlement funds allocated to improving neighborhood parks and schools will be open to community input, Brown said. Further details about how and where the money will be spent have not been announced.

Read more: Community organizing inspires Kensington Health & Wellness Corridors to improve public health

Community concerns over Kensington opioid settlement plans

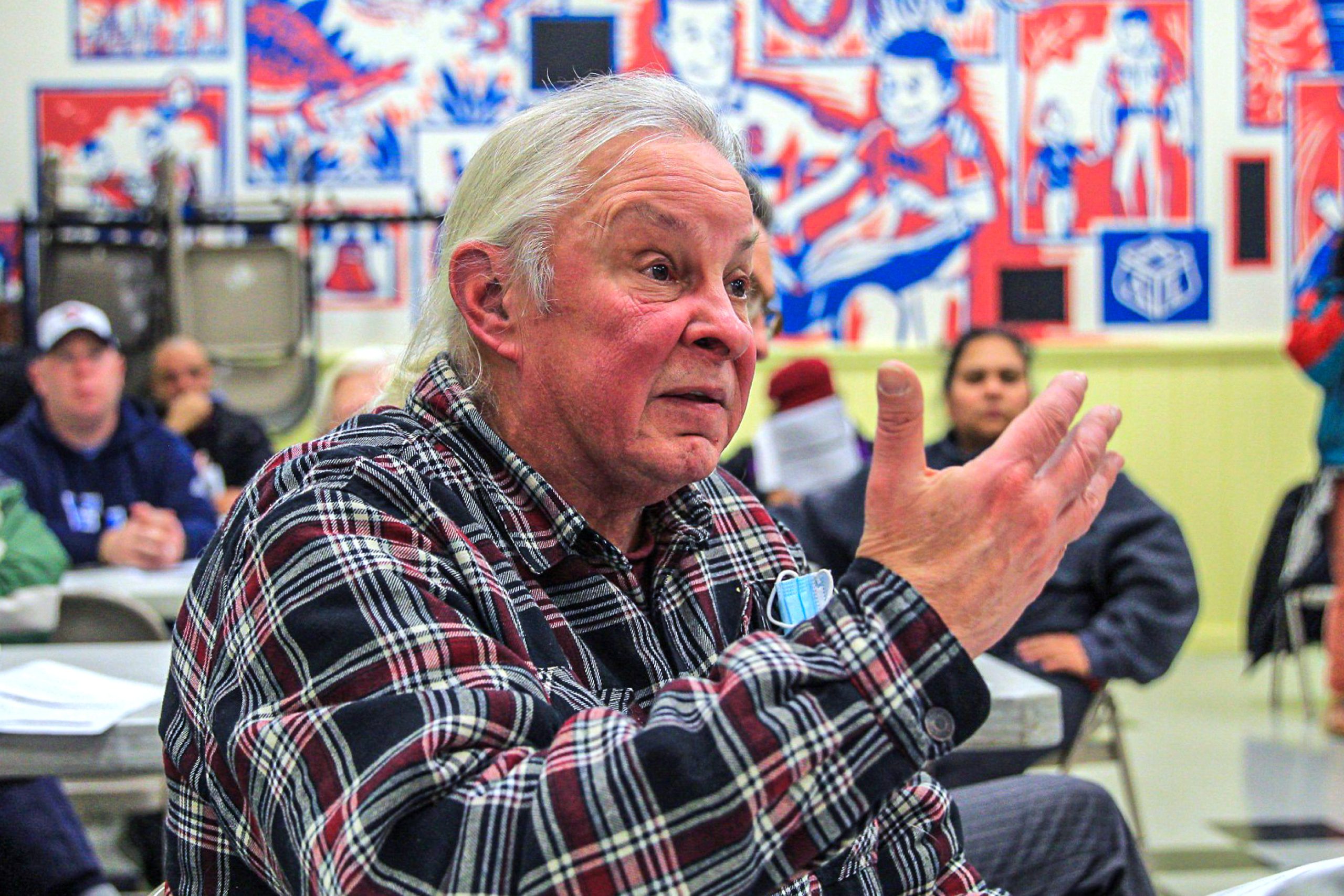

Since the City’s January press conference, the community’s confusion and skepticism over where the $7.5 million is going has been growing. Many of those concerns were aired during a Jan. 18 Kensington Independent Civic Association (KICA) meeting at the Harrowgate Police Athletic League.

The purpose of the January KICA meeting was to answer residents’ questions about the settlement funding, including the $7.5 million.

The meeting hosted several City officials, including Noelle Foizen, the director of the City’s Opioid Response Unit (ORU). Councilmembers Jim Harrity (At-Large) and Quetzy Lozada (District 7) were also in attendance.

“It’s not focused on the drug-addicted, the housing situation, [or] the trash all over the place,” said Angel Cruz, a longtime Kensington resident and former PA state representative, at the meeting. “We’re gonna get neglected, we’re gonna get short-handed if we don’t sit and be part of voicing how the money is spent in our community.”

Some residents voiced concerns that the money would not fund drug prevention programs or restore community assets in need of repairs, like McPherson Square Library. Others had concerns about the funding’s oversight, and how the money would help support current residents.

“On my block for instance, of the fourteen houses, nine of them have emptied out, then the drug dealers and addicts are taking over the houses” said Alfred Klosterman, a Harrowgate resident. “Do you recognize that this [plan] doesn’t really mean anything about that aspect of things?”

In response, Foizen emphasized that the opioid settlement funding is part of a wider approach to the opioid crisis’ impact on the neighborhood.

“This is just what we’re doing with the settlement,” Foizen said. “This is not everything that we’re doing across the board.”

According to Foizen, the ORU is an interagency effort that engages 35 city departments through four strategy groups, one of which is focused on public safety. Foizen said the public safety group is working on a drug market intervention.

“There is an effort right now to try to figure out a drug market intervention that is not just going to displace and push it somewhere else,” Foizen said. “It’s actually going to break it up and end it.”

However, residents emphasized concerns over the effectiveness of those efforts. Specifically, they demanded to know when the City would enforce the policies that are already in place to resolve issues related to drug sales and use.

“You know doggone right well you ain’t gonna see fifty corners open up in South Philly, so why is it tolerated here in Kensington?” said Darlene Burton, another community member. “What I can’t understand [is] we’re not asking y’all to invent anything new, we’re just asking y’all to enforce the already existing laws. You can literally see a cop, a dealer, and a addict standing side by side, like nothing.”

So, where did the $7.5 million come from?

The $7.5 million that the City announced it would spend in Kensington came from the national opioid settlement.

The settlement was the result of a four-year legal battle called the National Prescription Opiate Litigation. The litigation included a consolidation of over 200 lawsuits spanning from 2007-2021.

The party that initiated the litigation was the Plaintiff’s Executive Committee (PEC), which represents over 3,000 U.S. communities impacted by the opioid overdose crisis.

The defendants included pharmaceutical distributors AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson, plus pharmaceutical manufacturer Johnson & Johnson.

The litigation settlement required the defendants to provide $26 billion for the opioid settlement fund due to their role in the opioid crisis. Money from the settlement fund is distributed to each state based on a mathematical formula that calculates the opioid crisis’ impact.

Each state controls how to distribute the funding allocated to it. Each of their individual, publicly reported plans are available here. Pennsylvania received more than $1 billion. The state posted its plans for the funds here.

According to the City, Philadelphia will receive $200 million over the next 18 years. Of that funding, the City is receiving $20 million for 2023.

At the City’s Jan. 5 press conference, they announced their plans to spend the first year on seven initiatives:

- Kensington Wellness Corridors Investments ($7.5 million)

- Overdose Prevention & Community Healing Fund ($3.5 million per year)

- Citywide outreach and engagement ($2.75 million)

- Overdose response ($1.25 million)

- Treatment initiatives ($4 million)

- Housing for people experiencing homelessness ($3.7 million)

- Alternatives to incarceration ($250,000)

On the day of the press conference, the handouts the City provided said the “Kensington Wellness Corridors Investments” would include:

Support for residents

Targeted funding to help Kensington residents maintain their homes and quell gentrification. Support to keep people in their homes with repairs, rent relief, foreclosure support, etc.

Support for parks

Grants for Friends groups to identify investments toward maintaining parks as safe, drug-free spaces for youth.

Support for schools

Schools within the planning target area will receive funding. Site improvements on playgrounds; fencing, gates, cameras. Sign-on bonus for hard-to-hire staff, etc.

Which groups have taken ownership of the $7.5 million project?

There are three primary groups involved in the announcement and messaging around the $7.5 million for Kensington:

- The City, via the Mayor’s Office and Managing Director’s Office (including the ORU)

- Impact Services

- NKCDC

According to Brown, NKCDC’s Executive Director Bill McKinney and Impact Services’ CEO Casey O’Donnell met with the Managing Director’s Office in April 2022. During that meeting, McKinney and O’Donnell asked the City to support a community-driven planning process using the progress of the nonprofits’ Health & Wellness Corridors as evidence.

The nonprofits’ Health & Wellness Corridors are made up of anchor projects and supportive programs. The anchor projects include a series of pre-existing investments and coordination efforts around six community-prioritized properties for community resources, legal services, social gatherings, and housing in order to impact the health outcomes of Kensington residents. Meanwhile, the supportive projects are intended to improve the environment between these locations.

In December 2022, NKCDC learned that the City was planning to invest some of the opioid settlement funding in Kensington, Brown wrote in an email to Kensington Voice on March 6.

Then at the January press conference, Mayor Jim Kenney announced the $7.5 million “Kensington Health & Wellness Corridors master planning effort” funding. McKinney (from NKCDC) also talked about the $7.5 million spending and the planning process.

“Hopefully, these specific investments will help those suffering from addiction, from being unsheltered, will help families and children who have suffered for the crime of living here, will help our schools and parks so that we have the same things that everyone else in this room wants for themselves and their families,” McKinney said during the press conference.

McKinney added that “these resources will also add to a process begun by the community a couple of years ago. … and through this community-driven process, we will finally have an actual plan for Kensington.”

The handouts the City provided during the press conference sent people directly to the “Planning Kensington Together” website at kensingtonplan.org, which is managed by Impact Services and NKCDC. The website launched the day of the press conference and featured the Health & Wellness Corridors as the first phase of the planning process. It also invited community members and stakeholders to sign up to help plan Kensington’s future.

Since then, the website has changed. As of Feb. 13, the corridors’ projects, like the Kensington Empowerment Hub, are mentioned as an example of a “collaborative and resident-driven process.”

The Kensington planning process is described on the website as a “growing group … outlining the structure for community-driven, strengths-based, trauma-informed development in Kensington north of Lehigh Avenue.” According to Brown, there is no name for that process.

That group of residents and neighborhood groups will set neighborhood priorities, engage politicians, leverage infrastructure projects, and then put all the information together into a master plan, Brown said.

Here is a link to their planning timeline.

The community organizing that led to the $7.5 million investment

It’s been nearly two years since hundreds of Kensington residents protested the City’s temporary closure of Somerset Station.

“There have been a lot of different activities over the past couple of years, and I always point to the closing of Somerset Station,” said McKinney in an interview on Jan. 20. “It’s a moment when residents came together and said, ‘That ain’t gonna happen.’”

According to McKinney, SEPTA sped up its proposed timeline following the March 2021 protest. They addressed the safety and quality of life concerns that led to the initial closure. Two weeks later, the Market-Frankford Line station was open again.

The concerns that manifested themselves through these protests however, are nothing new. Neighborhood health and wellness has been a longtime concern for residents, especially when it comes to Kensington’s kids.

The summer following the March 2021 SEPTA protest, dozens of Kensington community members marched through Clearfield and D streets to a public City Council hearing at Lewis Elkin Elementary.

For three hours, residents and community advocates offered emotional testimonies about why they felt prior City interventions had failed. Among those interventions were the Philadelphia Resilience Project and the Opioid Response Unit. They also discussed the City’s response to the 2020 Restorative Investment Plan for Kensington Residents.

After that hearing, a large group of Kensington residents, community organizations, and other stakeholders came together to draft a letter to Mayor Kenney, McKinney said.

In that letter, published in February 2022, the group detailed their concerns about neighborhood safety and wellness. They made six recommendations to Mayor Kenney:

- Eliminate Kensington as a destination for narcotics use and support the reunification processes for those from outside of the area.

- Parks and Rec Centers should be immediately designated and enforced as safe spaces for children and families.

- Sanitation and usability of public spaces (sidewalks and parks) in Kensington should be given priority.

- Establish a concise reporting mechanism (i.e. dashboard) to demonstrate progress on implementation of actions listed above.

- Provide housing for all.

- Provide treatment for all.

According to ORU’s Foizen in an interview on Jan. 18, those recommendations resulted in the City having weekly meetings to discuss Kensington. Foizen said the City also regularly meets with community leaders. She said those meetings, in addition to the letter’s recommendations, helped inform decisions about opioid settlement spending in Kensington.

However, in the year since that letter was published, the concerns that led to those recommendations have persisted.

Throughout 2022, concerns about quality of life impacted several places and programs that promote health and wellness among kids, including McVeigh Recreation Center and Playstreets.

Relatedly, twice last spring and summer, the Free Library’s Lillian Marrero branch was forced to close after someone stole parts from the library’s HVAC system two times in under two months.

Most recently in December, residents circulated a petition pushing the City for repairs and renovations at McPherson Square Library, where a youth after-school program is held.

McPherson was forced to close its basement due to contaminated park runoff entering its walls. According to library workers, human waste from the park runoff was entering the building. After a several-week closure, the basement reopened on Feb. 17 following some temporary repairs.

What is the neighborhood planning process?

Now building off previous efforts and hoping to deal with current issues, NKCDC and Impact Services are urging community members to work together again. They hope residents will use the same energy they have in the past to shape the neighborhood’s plan for the development of Kensington north of Lehigh Avenue.

“What we’re asking of people is a commitment to work together and to center community-centered, trauma-informed, comprehensive approaches to things,” McKinney said.

The planning process is made up of five parts:

POCKETS

Identify and bring together existing and emerging neighborhood groups to identify their specific needs, desires and vision for the community, and share them across all the groups. We will have a goal of supporting at least 20 pockets with a template for the engagement process so that all groups produce similar materials at the end.

PRIORITIES

Support pockets in collecting and organizing priorities for their group, similar to a point-by-point list presented to the Mayor a year ago. These community lists will serve as a starting point for a series of forums over the next year and inform the major areas to focus the planning process.

POLITICS

Host a series of five candidate forums, each of which will be sponsored and facilitated by the pairing of a local community development corporation (HACE, NKCDC, Impact) and the surrounding civic organizations or active “pocket” groups. Each will focus on the issues that are most relevant to the sponsoring groups.

PROPERTIES/PROJECTS

Leverage infrastructure—buildings, open space, etc.—that is currently under development to move projects, programs, and community priorities forward.

PLANNING

Pull together leadership and materials from community groups, and combine needs and desires into a comprehensive neighborhood plan that has mechanisms for ongoing engagement and repetition of these steps.

Can I join the planning process?

To get involved in the neighborhood planning process as an individual, civic association, community group, or community organization, visit www.kensingtonplan.org/join-in and sign up. You can also get involved through the following neighborhood groups or “planning pockets” that have already signed up:

- East Kensington Neighbors Association

- Fab Youth Philly

- Gloria Casarez Elementary School

- Harrowgate Civic Association

- Impact Services

- Kensington Neighborhood Association

- New Kensington Community Development Corporation

- Save Our Neighborhoods (SON)

- Somerset Neighbors for Better Living

You can view their planning timeline over the next few months here.

Although NKCDC and Impact Services are overseeing the process, McKinney emphasized that its future belongs to Kensington residents.

“We’re just serving as a vehicle to say, ‘Come to the table,’” he said.

Meanwhile, stakeholders like the City and special interest groups can take a backseat by pledging their support and providing expertise and investments. To sign up or see the full list of supporters, click here.

The City’s Opioid Response Unit is one of those supporters. It formed in early 2020 following a series of interventions addressing the overdose epidemic, including the Mayor’s Opioid Task Force (2016) and the Resilience Project (2018).

According to Foizen, the City plans to contribute to the planning process in the same way as other stakeholders.

“We do not in any way own this planning effort,” Foizen said. “We’re just gonna have a seat at the table just like any other community member.”

Editors: Jillian Bauer-Reese, Siani Colón, Zari Tarazona Designer: Zari Tarazona

This content is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit www.everyvoice-everyvote.org. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.