This story was originally published by The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom covering gun violence in America. Sign up for its newsletters here.

Five seconds. Six shots. A hundred steps back.

On August 14, Officer Mark Dial and his partner were on patrol in Kensington when they spotted Eddie Irizarry, 27, and followed him onto Willard Street, where he was driving the wrong way. The officers parked, got out of their marked police car, and five seconds later, Dial fired six bullets at Irizarry, video evidence shows.

Initially, a Philadelphia Police Department spokesperson misstated how and why Irizarry had been killed. Before the video footage from a neighbor surfaced, the spokesperson erroneously said that Irizarry, a native of Puerto Rico who didn’t speak English, had gotten out of his car and lunged at the officer with a knife before being shot. Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw corrected the record a day later.

Attorney Shaka Johnson, who has been hired by Irizarry’s family, said Irizarry had never been in trouble and supported himself working as a handyman mechanic. The lawyer said he was holding a knife in his right hand by his right knee when he was shot.

The killing has become the latest flashpoint in the strained relationship between cops and Philadelphians. Its aftermath — including the changing, and, at times, wrong police narrative — has resulted in what many believe to be a test for how city officials police the police.

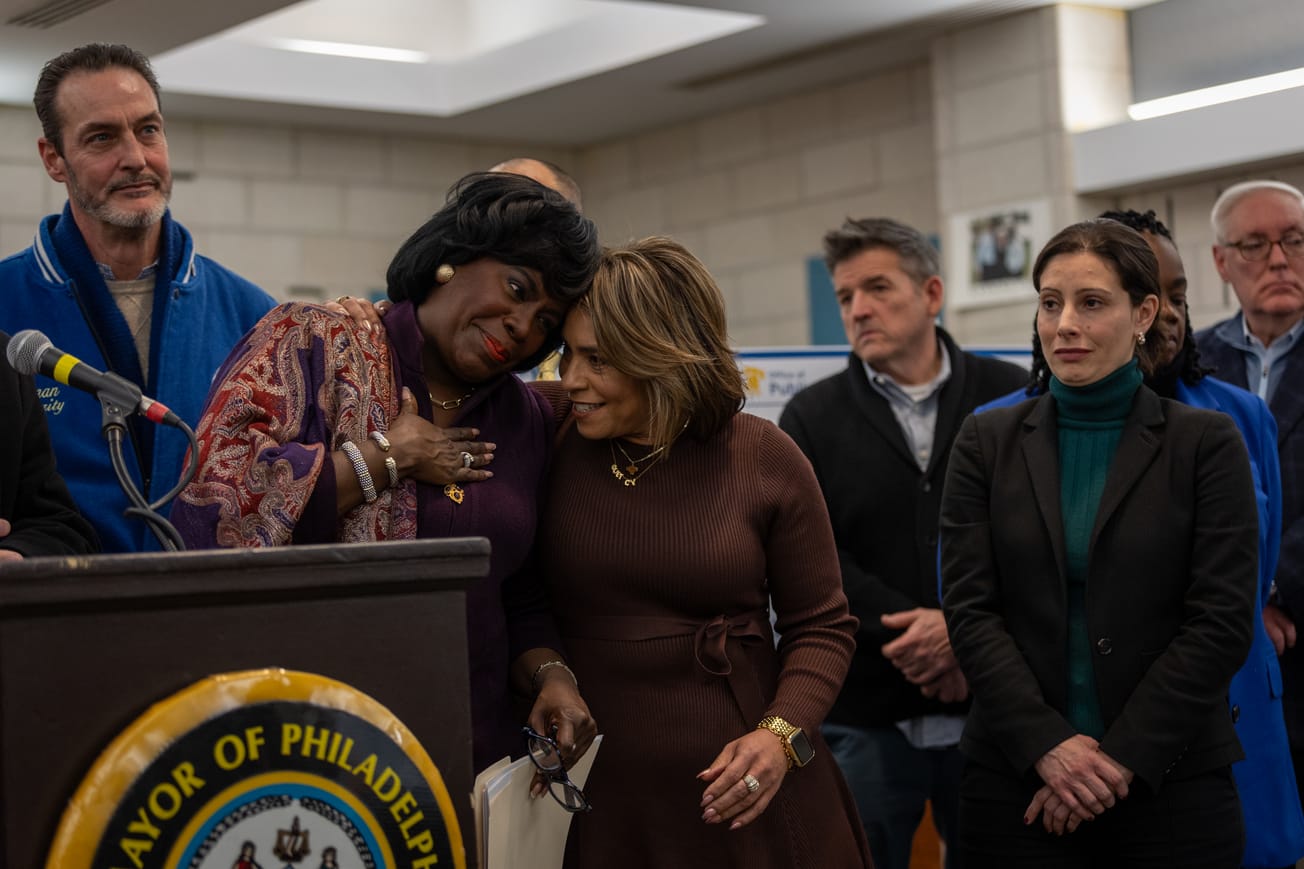

“It feels like when we take fifty steps forward, sometimes we’re taking a hundred steps back,” a beleaguered Outlaw said at an August 23 news conference. There, she announced that she would fire Dial, a five-year veteran, for failing to cooperate with the investigation and refusing to obey orders from a superior officer.

In the days and weeks after Irizarry’s killing, his family and community members demanded Dial’s firing, arrest, and the release of police body-worn camera video. By September 8, when District Attorney Larry Krasner charged Dial with murder and related counts, all of those demands had been met. But for many, the strong sentiment of distrust expressed after the shooting remains.

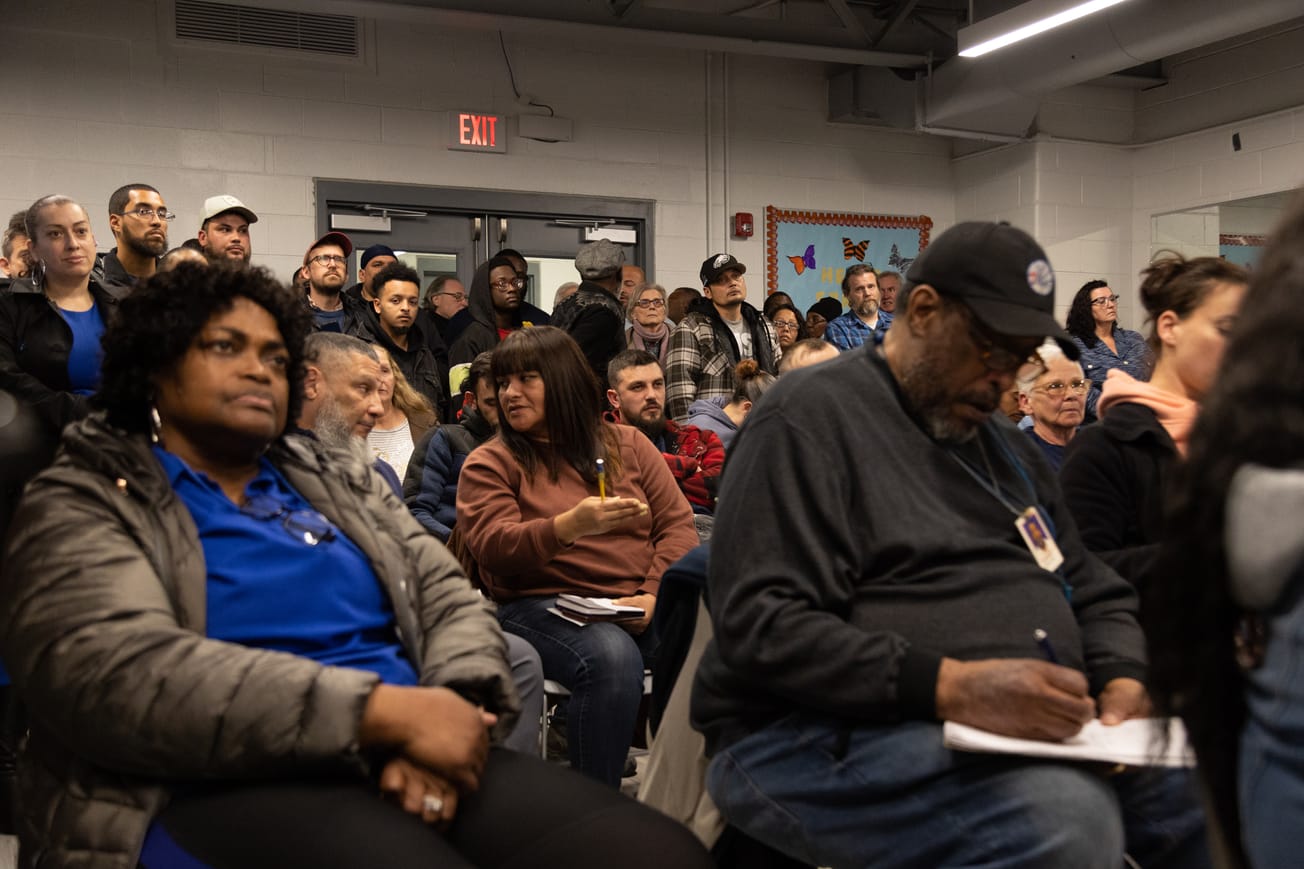

In late August, a crowd marched from Taller Puertorriqueño, an arts and culture center, to the location where Irizarry died, then to the nearby district police station where Dial was stationed. Every step of the way, they called for systemic Police Department reforms. “When that officer got out of that car, it was five seconds before Eddie was killed. Five seconds. Let me explain something to you. No amount of training, no amount of Tasers, would have changed that,” Abolitionist Law Center Executive Director Robert Saleem Holbrook told the group. “That officer got out of that car with the intent to kill.”

“We want more structural changes as a community because if not…we’re going to be in the same place, not just next year, this could be tomorrow. This literally could be tonight,” Holbrook said.

Maria Cruz, Irizarry’s aunt, stood on the porch of her home and gazed at the marchers when they stopped to pray and leave flowers at an altar, near where he died.

“I have a lot of cops in my family. I have nothing against the police, nothing at all. But we know that was unbelievable,” she said of the shooting. “If he was anybody else who shot Eddie he would already be in jail. He made a mistake. There were a lot of things he could have done, a stun gun, pepper spray. He didn’t even let him get out of the car.”

Cheri Honkala, a longtime community and anti-poverty advocate, said: “People are deathly afraid of the police here, especially if you’re a young man. Anybody that’s driving, I don’t care who they are, if they get pulled over, they go into a panic attack.”

A history of distrust, a precarious moment

The killing comes at a precarious time in Philadelphia’s drive to end its gun violence crisis, which has claimed 1,700 lives since 2020. Homicides are down 20 percent from this time last year, while still remaining much higher than they had been in pre-pandemic years.

Police officials have credited the drop in part to the redeployment of additional officers in gun-violence hotspots, including Kensington, where Irizarry was killed. City officials have also attributed it to the ending of pandemic restrictions that limited the public’s access to social services, a decline in gun sales, and the city’s launching of a handful of anti-violence grassroots programs.

These strategies, along with a new effort by Krasner and Sheriff Rochelle Bilal to arrest more homicide fugitives, rely on establishing buy-in and receiving help from the public. But for that to work, and for police to garner witness accounts when trying to solve killings, the public has to trust law enforcement.

“We are realistic enough to know that we cannot read the minds of the public,” Krasner said. “But what we can do is try to control our own decision making.”

With public calls for Dial’s arrest swirling, Outlaw, the first Black woman to lead the 6,000-officer city police force, announced her resignation about two weeks later, saying she was stepping away from the department she’s led since 2020 to take a job with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Her departure leaves the future of Philadelphia’s relationship with law enforcement in the hands of the city’s next mayor.

Voters will go to the polls to elect a new mayor in less than two months, a race in which public safety has been among the leading issues. Both candidates, Democrat Cherelle Parker, the frontrunner, and Republican David Oh, have embraced the Police Department and praised Outlaw after news of her resignation broke. Neither has made a public statement about the killing of Eddie Irizarry. A spokesperson for Parker said she did not have all the facts and therefore would not comment. Oh’s campaign did not respond to a Trace email.

Outlaw is leaving a department that, for decades, many in the city’s Black and brown communities have viewed as an unwelcome occupying army. A 2015 federal Justice Department review of the force found that police shootings were rising while crime was falling, and that the force had inadequate training and lacked transparency. The review also found that 80 percent of people shot by police between 2007 and 2014 were Black, 45 percent of them were unarmed.

Under Outlaw’s leadership, police fatally shot 17 people, a slight increase from the 14 people killed in 2016 through 2019. Citizen complaints accusing officers of using excessive force and other violations have fluctuated little from 2018 through last year, with more than 600 complaints filed in each of those years.

While the killing of Irizarry sparked outrage and protests, there have been no reports of street violence nor clashes with the police, unlike the mayhem that swept pockets of the city in 2020 following the police killings of George Floyd in Minnesota and Walter Wallace, a father of nine who Philadelphia police killed after he approached two officers holding a knife while he experienced a mental health episode.

Krasner, for the second time in as many years, had to weigh whether a terminated officer’s fatal fire is a crime or a justified action. Since taking office in January 2018, Krasner has charged four cops for on-duty fatal shootings.

“We can survive a whole lot of things, but you can’t kill one of our babies and not have justice,” Honkala said.

'It’s in every minor interaction’

Some have begun assessing how the relationship between cops and citizens can improve in the wake of Irizarry’s killing and the department’s botched response.

“The Police Department and the city of Philadelphia now have an opportunity to build bridges and make changes so that the community knows that they can trust and rely on the police department,” said Anthony Erace, interim executive director of the Citizens Police Oversight Commission.

The commission, which investigates and monitors the Police Department and makes recommendations to the city and department, viewed body camera video from Dial and his partner, and called for Dial’s firing a day before Outlaw announced his termination.

While police killings make headline news, Erace said, microaggressions are also a factor in people’s perceptions of police.

“It’s not really big shooting incidents like this that destroys relationships,” Erace said. “It’s in every minor interaction that an officer has with a resident. Asking for directions and getting a rude response; calling for help and help comes four hours later. Those are the things that cause relationships to go bad and stay bad, and they’re exacerbated by incidents like this shooting.”

Honkala worries for the safety of her 20-year-old autistic son and for her 8-year-old foster son, who is Black. Her worries extend to the impoverished Kensington community, where Irizarry was killed, and the center of Philadelphia’s opioid epidemic. “There isn’t the same kind of due process here that would happen in Mt. Airy or on the Main Line or in Center City,” she said. “Here, particularly if you’re a man of color, they just shoot. You’re fair game.”

“Police relations with the community have improved through the years, considerably. Unfortunately, this incident, and the way the commissioner has handled it, has eroded some of that trust,” said state Representative Danilo Burgos, in whose district the shooting took place. Burgos, who’s been in office since 2018 and a civic leader for more than 35 years, said Dial needs to be held accountable.

Johnson, the Irizarry family’s attorney, said his clients are prepared to fight for justice. “They are devout Catholic supporters of law enforcement. They would have never thought that they would be in this kind of situation, whatsoever,” said Johnson, a former police officer who secured a $2.5 million settlement from the city for the family of Walter Wallace. “They thought that this kind of thing was reserved for certain people and places — not for them.”

Johnson, like many others, bristles that the officer who killed Irizarry was not fired for killing him. “He was terminated for policy violations, not for a reason that this family could feel vindicated by,” said Johnson, who sees parallels in the killings of Irizarry and Wallace, who was Black. “He wasn’t terminated for a reason that would make the community feel like the police are policing their own.”