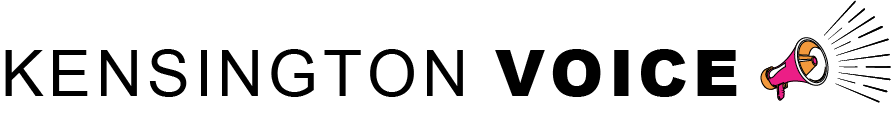

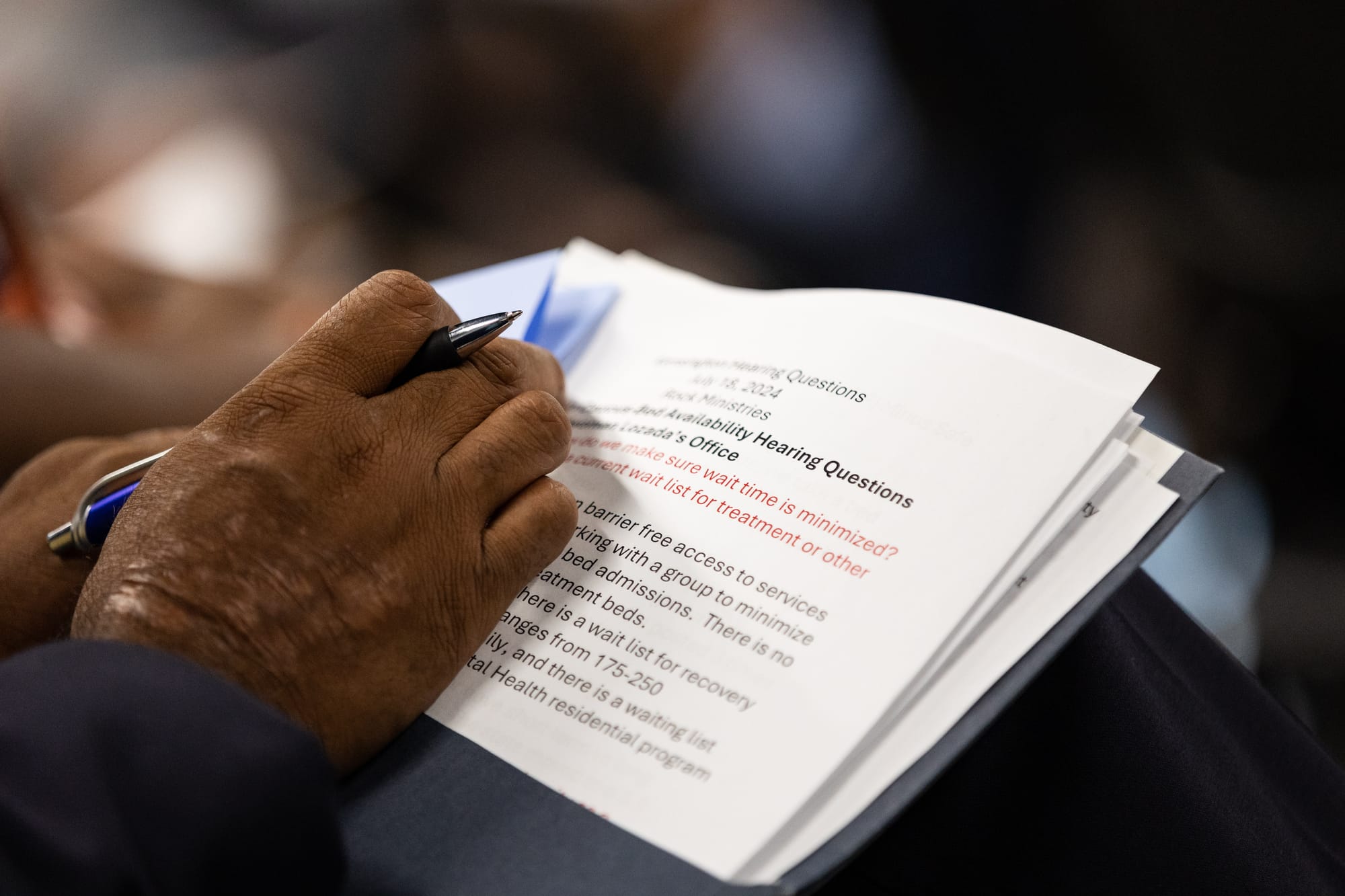

During a six-hour City Council committee hearing at Rock Ministries on Thursday, addiction experts testified about treatment barriers complicated by an increasingly complex drug supply that has disproportionately impacted Kensington.

Local health experts emphasized system-wide challenges, ranging from 16-hour assessment wait times to a lack of coordination among service providers, shortages of medically monitored treatment beds, and insurance policy limitations.

They also encouraged the city to support resources that would reduce barriers to treatment access, such as harm reduction programs and facilities that treat couples, LGBTQ people, parents, and non-English speakers.

Several healthcare workers named Prevention Point, which has recently faced funding cuts and community pushback for providing medical services without the proper zoning permit.

“People who interact with syringe service programs and other harm reduction organizations are five times more likely to enter treatment than those who don’t,” said Dr. Maggie Lowenstein, research director at Penn Medicine’s Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy. “I think that’s because these types of programs are often the only places where patients feel welcome and safe.”

Some highlighted potential solutions for streamlining treatment services, including a centralized online dashboard with real-time treatment bed data. Others suggested creating a single phone line that street outreach workers can call to find open beds.

Outreach workers do not want to get “shuffled around” like they do now, according to Deja Gilbert, president and CEO of addiction treatment provider Gaudenzia.

“It has to be minutes,” Gilbert said. “It cannot take three hours to figure out who has a bed because that individual is back on the street – they are not coming back with you.”

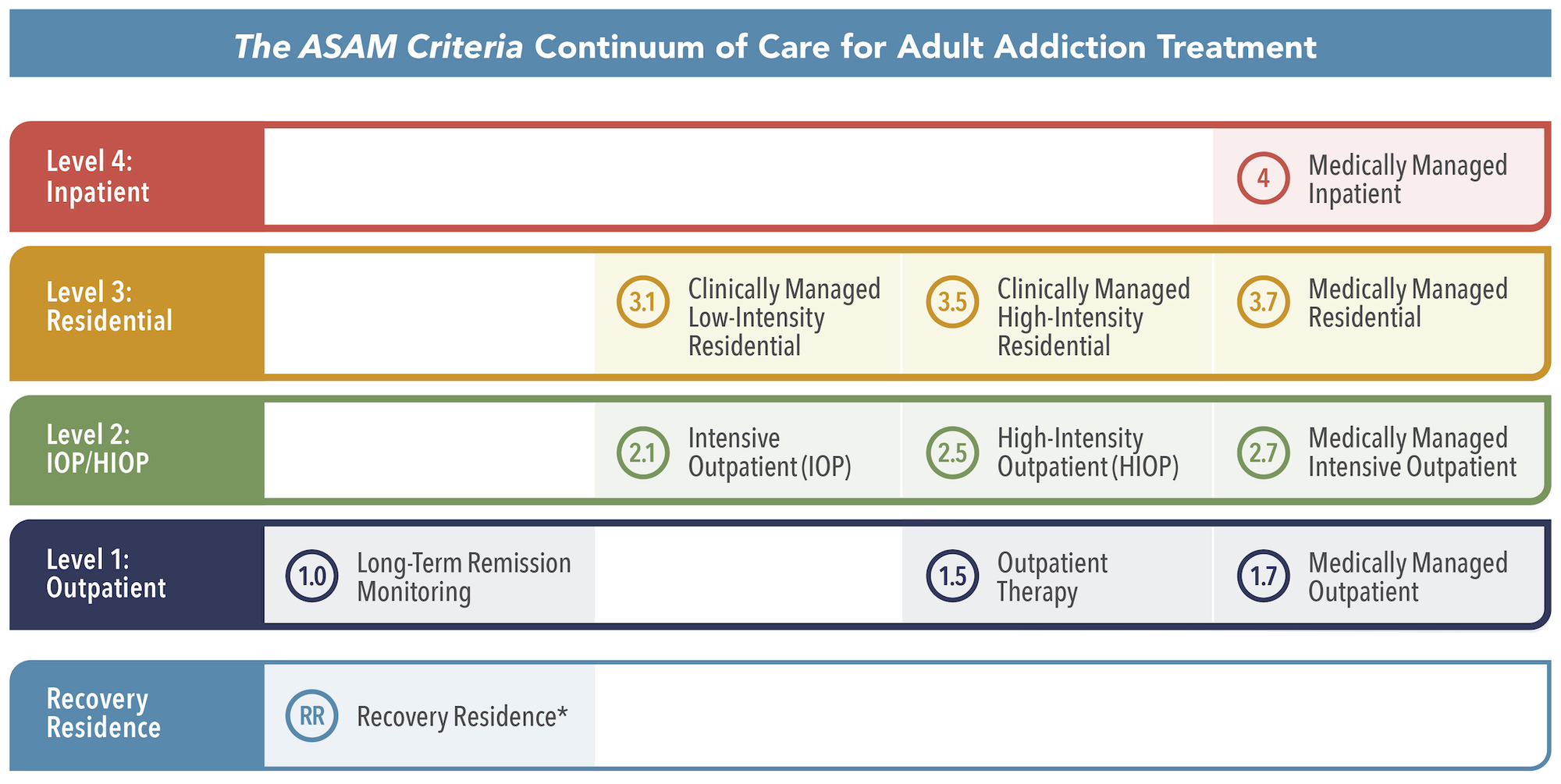

Levels of care

Most of the hearing centered around the four “levels of care,” a set of care standards developed by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) for addiction treatment placement, service, and transfer of patients.

According to Amanda David, interim deputy commissioner for the city's Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual DisAbility Services (DBHIDS), the city’s providers use ASAM’s model to determine what level of care a person requires and refer them to a treatment provider that can offer a treatment bed with that level of care.

Andrew Devos, chief operations officer at DBHIDS partner Community Behavioral Health, said the ASAM levels of care are represented by a score from 1.0 to 4.0, with 1.0 being the lowest level of care required and 4.0 being the highest.

Devos described a 3.5 as “your typical rehab” for people without significant medical problems, a 3.7 as someone who requires “high psych and/or a high medical team,” and a level 4 as someone with chronic medical conditions.

“They’re going to need 24/7 nursing,” Devos said.

Pennsylvania requires providers to use the ASAM levels of care system to collect Medicaid for substance misuse treatment, he said.

Increasingly complicated needs

Dr. Philip Durney, a hospitalist and clinical assistant professor with Jefferson Health, also stressed how the “dynamic drug supply” has increased the complexity of patients’ needs and the level of care they require.

Between acute withdrawal syndrome requiring medically supervised withdrawal management and treatment for medical complications – such as xylazine-induced skin ulcers – patients are increasingly challenging for healthcare facilities to manage, Durney said.

“Our patients are suffering from severe complications of drug use that often require prolonged treatment interventions, like weeks of intravenous antibiotics for infection control, aggressive wound care management, and rehabilitation from amputations and spinal cord injuries that have rendered them unable to move or function,” said Durney. “Most inpatient substance use treatment facilities that offer rehab beds are unable to support these patients’ ongoing medical needs.”

While Gilbert testified that Gaudenzia had an average of 28% of beds available daily in the last fiscal year, others detailed their challenges with finding treatment centers that can provide people with the required level of care.

“Not every provider has the exact same level of care,” said Natasha Lundy, the mobile police-assisted diversion (PAD) director for Merakey. “Eagleville has a level 4 that can handle acute medical care; Kirkbride can’t handle that in their facility.”

Open treatment beds

As of Thursday, the city’s network had 121 open treatment beds. Of those, 77 were level 3.5, 30 were level 3.7, and 15 were level 4.0, David said.

There were 828 people experiencing homelessness in Kensington during the city’s last point-in-time count on May 15, which accounted for over 63% of the city’s 1,303 unhoused population that day, according to David. She said a majority of the people living unhoused in Kensington have a substance use disorder but the city’s count does not include which level of treatment each person would require.

“By my layman’s diagnosis of looking at them and interacting with them, they’re all 3.7 to 4.0,” said Jim Harrity, at-large council member. “So why are we even messing around with the other stuff? Let’s make them all 3.7 to 4.0 and be done with it and get everybody into treatment.”

Devos suggested discussing the idea with the Pennsylvania Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs, which is responsible for licensing treatment facilities in Pennsylvania.

City Council’s Special Committee on Kensington organized the hearing, chaired by District 7 Councilwoman Quetcy Lozada, joined by Kensington caucus members Mark Squilla (District 1), Mike Driscoll (District 6), and Harrity (at-large), plus council members Curtis Jones, Jr. (District 4) and Nina Ahmad (at-large).

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.