Content warning: This story includes descriptions of sexual assault, including sexual violence against women and children.

At about 5 p.m. on Friday, a former Kensington police officer who sexually assaulted vulnerable women and prepubescent children while working in at least two North Philly police districts watched as court clerks drew up his Megan’s Law paperwork.

The prosecution’s explanation that Patrick Heron, 54, is now required by law to register as a lifetime sex offender marked the end of an unexpectedly dramatic, hours-long hearing in a mostly empty courtroom at the criminal justice center on Filbert Street.

Heron, who worked as a police officer for the Philadelphia Police Department (PPD) for 24 years before retiring in 2019, wore a dark green prison jumpsuit and thick aviator glasses. There was nobody there to support him.

Heron’s face was pale, and his knuckles were white as his thumbs tightly gripped the courtroom table. His eyes nervously darted around the room as others made small talk while the court’s staff waited on the printer.

Just two hours earlier, Heron refused to take a plea deal for 17 to 40 years despite facing over 200 sex crime charges for which prosecutors had an overwhelming amount of photo and video evidence that connected him to at least 48 female victims.

The offer, prosecutors said, was an attempt to avoid a jury trial that would cause Heron’s victims additional trauma.

“It is unconscionable that a 10-year-old runaway who is then contacted by a police officer who then assaults her – that we are going to put her through going to trial,” said Lyandra Retacco, the assistant district attorney leading Heron’s case and supervisor of the District Attorney Office’s Special Investigations Unit (SIU).

Retacco also stressed to the judge that a critical logistical challenge of Heron’s case going to trial would be responsibly handling the sensitive nature of the prosecution’s evidence. Much of their evidence included photos and videos – “trophies,” – Retacco said, of women and children “in various states of undress while he was in a police car.”

At the start of the hearing, Anthony List, the second attorney to represent Heron in this case, requested that the judge withdraw him from the case due to Heron’s unwillingness to accept the prosecution’s initial offer.

“We’re not in a very good position to go to trial,” List said.

However, after Retacco reiterated the severity of the 200-plus charges against Heron and the large amount and weight of their evidence – including a prison phone call recording in which Heron allegedly threatened to kill a witness – Heron was more receptive to taking a plea offer.

“All I need to do is get out of here so I can kill one of these witnesses so the case will go away,” Heron allegedly said in the prison call recording.

Additionally, prosecutors shared that if Heron officially rejected the offer – “which expires today,” Retacco said, they would likely pursue additional charges, for which the last time they did the math, he could face up to 1,300 years in prison.

“It spans an enormous period of time… it is one of the most alarming cases I have ever seen,” Retacco said on Friday. “Most of the charges do not merge – there are literally thousands of years of charges.”

“It will likely be a historic sentence in this building,” Retacco added.

Heron’s final plea agreement

The 17-to-40-year offer Heron was initially given followed his September 18 court appearance, during which prosecutors sought permission to combine all of the charges against him into one trial.

By the end of last month’s hearing, where Retacco’s team shared a fraction of the photo and video they said they collected of Heron sexually assaulting women and children while on duty in his patrol car, the judge agreed that there was a pattern of conduct that required the cases' consolidation.

All of Heron’s arrests and subsequent charges, prosecutors said, stemmed from a conflict at Austin Meehan Middle School, where his daughter was a student. He was first arrested in April 2022, and by June 2023, his charges ballooned from three to over 200.

In court on Friday, upon hearing the prosecution’s final pleas for Heron to accept their offer, he turned to his attorney and asked him what to do.

“If they give me 10, I’ll do 10,” Heron whispered to List.

After a last-ditch negotiation that involved a flurry of private phone calls to Heron’s identified victims, the prosecution gave their final offer – 15 to 40 years.

“I won’t go any lower,” Retacco said. “I think that’s a gift he doesn’t deserve.”

Finally, Heron accepted the second offer, pleading guilty to the following:

- 2 counts of Unlawful Contact with a Minor

- 2 counts of Sexual Abuse of Children

- Involuntary Deviate Sexual Intercourse

- Official Oppression

- Kidnapping of a Minor

- Indecent Assault

- Forgery

- Stalking

Those charges were connected to a total of five criminal cases against Heron.

Heron’s “well-chosen” victims

During Heron’s tenure with the PPD, he worked for the 23rd, 24th, 25th, and 39th Districts, according to a PPD spokesperson. He began working for the 23rd District in 1995, the 24th District in 1997, the 39th District in 2001, and the 25th District from 2010 until his retirement.

While Heron was on the police force, he targeted vulnerable women and girls who would be less likely to report a sexual assault, prosecutors said. Those victims included unhoused women, runaway children, and children in police custody. Most of the dozens of victims connected to Heron’s charges remain unidentified “Jane Does.”

“Several of them were trafficked women who were in the throes of their addiction, who were engaging in acts of prostitution in and around Philadelphia turning to Mr. Heron as an authority figure, as a police officer in uniform in a police car,” Retacco said at a Monday press conference. “On at least one occasion, we can confirm that he in fact threatened arrest of a woman in exchange for sexual acts. In other words, ‘If you perform these sexual acts, I won’t arrest you.’”

According to Retacco, Heron would not only victimize sex-trafficked women and children, but also attempt to bring children into the sex trafficking industry.

“He would ask these children if they had ever thought about doing sex acts for money and if they would like to try and start with him for practice,” Retacco said during Friday’s hearing.

In at least one of those cases, Retacco said Heron threatened one of the children he victimized with arrest by his “buddies in the 7th” District. She said his victims were “well-chosen” for their vulnerability.

“We believe there are more victims – we know there are more victims,” Retacco said during Monday’s press conference. “Many of the trafficked women in the videos that we’ve recovered remain unidentified.”

Heron’s power: Force, fraud, and coercion

In 2010, Susan Brotherton, a Temple University social work professor who previously worked for the Salvation Army as the director of Philadelphia social service ministries, helped start the New Day to Stop Trafficking Program drop-in center on Kensington Avenue.

The idea for the center came from a collaborative community response to Antonio Rodriguez, known as “the Kensington Strangler,” Brotherton said, who sexually assaulted and murdered at least three women who were involved in the sex trade between November and December 2010 in Kensington.

Various groups, including the youth-serving organization Covenant House, were involved in creating the respite, which serves women and nonbinary individuals exploited by the sex industry, Brotherton said.

“With [Heron], look at the power that he could wield, not only as an officer, but even as a man on the Ave.,” said Brotherton, in a phone interview with Kensington Voice. “He could easily, easily groom some folks and persuade them that he could protect them or incarcerate them – it could go either way.”

Except for situations involving minors, in which any engagement in commercial sex is considered sex trafficking, the federal definition of sex trafficking makes clear that for it to occur, three things need to happen: force, fraud, and coercion. Sex trafficking perpetrators look for very specific red flags when choosing their victims, Brotherton said.

“Clear vulnerability, sometimes something that can make someone an ‘other’ – perhaps not speaking the language fully, can make people a little bit more vulnerable,” said Brotherton. “Think about things that happen in people’s homes – living around violence… poor families – moms sometimes have to work a couple of jobs, and dads do, too, which then leaves the kids home alone.”

According to Heather LaRocca, New Day’s director, in addition to the vulnerabilities Brotherton mentioned, addiction is also a risk factor.

“In Kensington, we see a lot of exploitation related to substances,” LaRocca said during a phone interview. “If someone has an addiction, it’s very easy to control that person, so we've seen traffickers really utilize the addiction as a method of controlling access to the substances.”

In 2022, New Day’s drop-in center served over 900 unique individuals, averaging between 40 and 80 per day, according to LaRocca. While each individual’s story is unique, she said there are still patterns of victimization.

“The amount of domestic violence, sexual assault, and trafficking that the women that we serve experience is endless and intense,” LaRocca said. “And it’s oftentimes started from very young that they’ve experienced that.”

In recent years, New Day has grown to offer programs and services beyond the drop-in center, such as housing, mobile case management, and police-assisted diversion (PAD). New Day’s PAD program, which started in 2018, engages people who have been arrested for low-level offenses, screened, and diverted to their social service programs.

Still, LaRocca noted one challenge of the PAD program is that it is not necessarily pre-arrest, but pre-arraignment. That means the clients referred to them are often referred after they’ve been arrested by police officers.

However, she said that one of their goals is to increase social referrals made by police, which are referrals unrelated to arrests. Those, she said, account for most of the referrals they now receive through the PAD program.

“The current system that exists is that police are currently interacting with individuals for these reasons, like prostitution, petty theft, and all these things that might be related to substance use,” LaRocca said. “So the way I’ve approached our relationship with police is if I can get in the room, if I can have that moment with a client who’s vulnerable who needs support, I will take that opportunity.”

Still, LaRocca recognizes the complications that arise with police partnerships due to the differences in how they view the same individuals.

“It obviously is a tricky relationship when you’re partnering with the police force arresting who we see as often victims, or at the very least vulnerable folks who’ve been exploited,” LaRocca added.

Brotherton noted similar challenges.

“When cops are raised to chase the bad guys, that's the way they see the issue,” Brotherton said.

Heron’s history of police misconduct

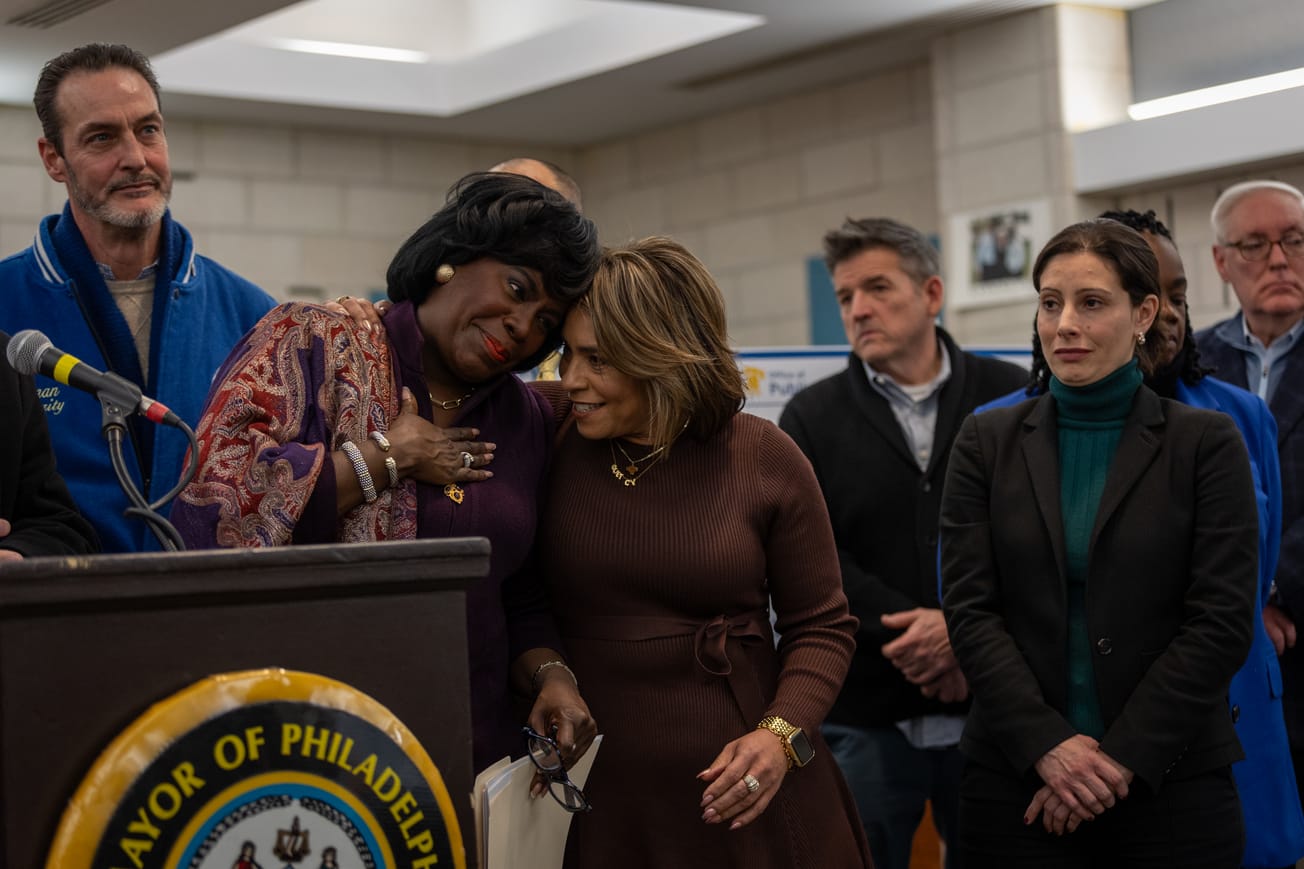

During Monday’s press conference, Retacco said that the PPD is going to conduct an internal review to determine how something like this could happen over such an extended period of time.

According to the PPD’s Internal Affairs records, Heron received at least 12 complaints between 1996 and 2016. Five of those complaints were for physical abuse, four were for harassment, two for lack of service, and one for departmental violations.

In one case, Heron was reprimanded, and in three others, he was suspended for three, five, and 12 days total. Otherwise, the PPD exonerated him or identified the complaints as unfounded.

The PPD could not be reached for comment.

Sammy Caiola contributed to this story.

Additional resources

For people with information about this case

Victims and witnesses who may have more information about this case are urged to contact the DA Office's Special Investigations Unit at 215–686–9608 or DAO_SIU@phila.gov. The Victim Services Unit can be reached directly at 215-686-8027 or DA.VictimServices@phila.gov.

For victims of sexual violence

The WOAR Philadelphia Center Against Sexual Violence is available 24/7, 365 days per year, free of charge. The services are entirely confidential to ensure all have a safe place to turn to for help and healing. Just call their hotline at 215-985-3333. Resources for victims of sexual assault are also available through the the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 800-656-4673 and the National Sexual Violence Resources Center.

For those who suspect child abuse

In Pennsylvania, the toll-free ChildLine hotline is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week at 1-800-932-0313. Mandated reporters can file a report electronically.

For victims and survivors of sex trafficking

Salvation Army's New Day to Stop Trafficking program offers drop-in services, housing, mobile case management, police-assisted diversion, and hotline help for those engaged in the sex trade in Philadelphia. Their drop-in center is located on Kensington Avenue between Hart Lane and Cambria Street. Their 24/7 human trafficking hotline is 267- 838-5866.

This story was edited by Siani Colón. Email Siani at siani@kensingtonvoice.com.