Conwell Middle School will no longer close, Philly school district says

The decision to spare the two schools from proposed closures comes after nearly a month of intense community pushback against the district’s sweeping facilities plan.

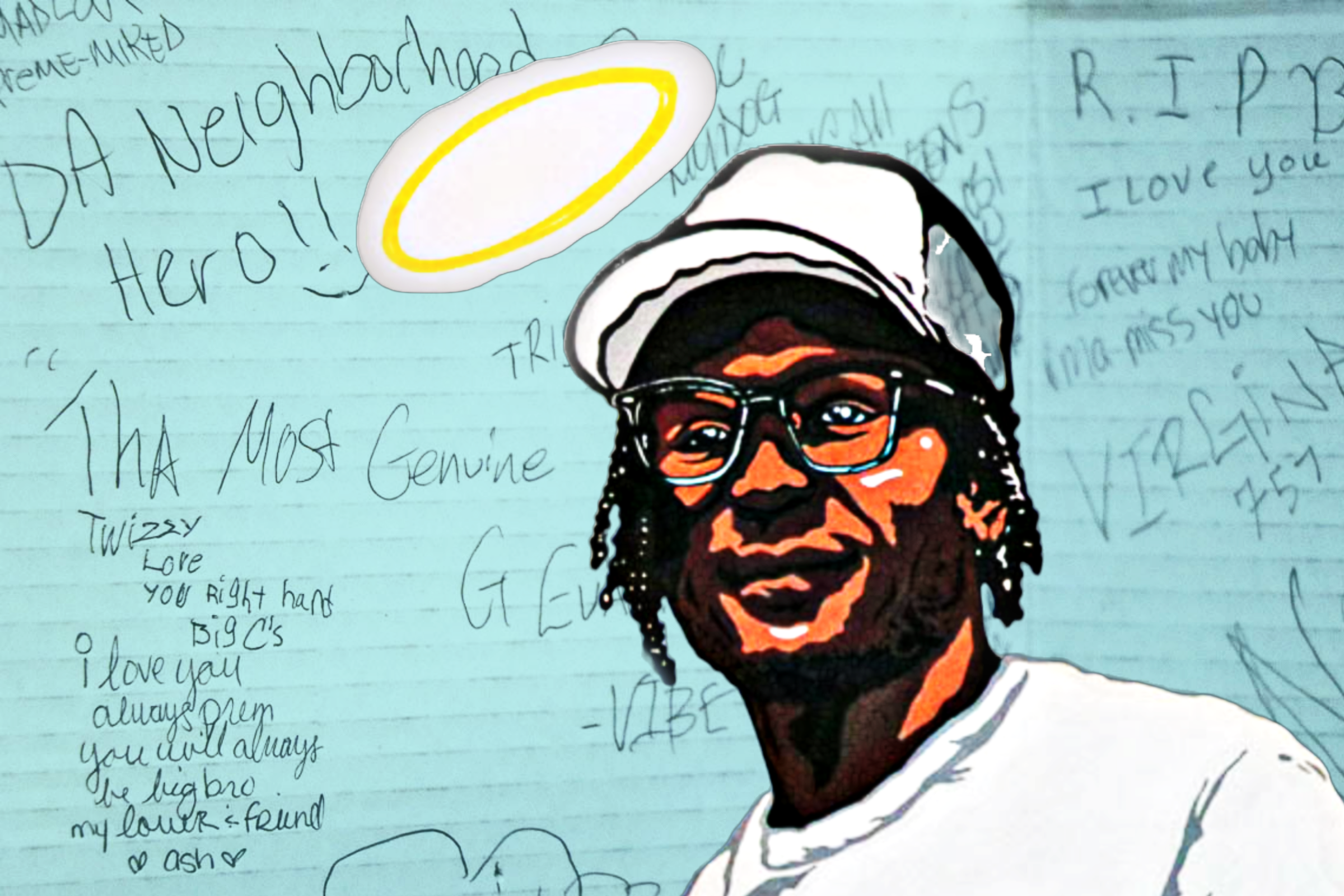

In one of his final conversations, Randolph "Primo" White told a friend, "When I die, people are gonna remember me because of all the good deeds that I’ve done; they gonna remember me in these streets – how I was.”

On Wednesday, hundreds of people gathered at Compagnola Funeral Home on North 5th Street to celebrate the life of Kensington anti-violence leader and youth advocate Randolph White, known by family as “Randy” and most others as “Primo” or “Preme.”

White, who played a central role in building up the creative hub and pro-youth organization Ride Free at Allegheny Avenue and Emerald Street, died in a motorcycle accident on July 22. He was 44 years old.

At the service, many wore black-and-white clothing embroidered or printed with images of White in his thick black-framed glasses and messages like “L4P” (Live for Preme) and “Long Live Preme.” Loved ones filled the guestbook with entries like "ride free forever" and gratitude for White's kindness and positive impact on their lives.

There was also an open microphone for tributes through spoken word, poetry, and song. Footprints by T.O.K. played between testimonies.

Friends and family remembered White as “well-manifested,” with "high-vibration energy" and how he "danced crazy" and "would make sure everybody knew he was from Brooklyn – everybody."

They also described White’s work feeding and clothing the neighborhood, and connecting community members with job certifications and employment, especially those at risk for gun violence and selling drugs.

“He was the calm to a lot of people’s storm – at a time, a storm of his own,” shared White’s friend Charlie McKnight, during the service.

White was buried, as longtime friend Kimberely Johns described, “fly from head to toe,” in his signature jewelry at Greenmount Cemetery on North Front Street.

During the burial, White’s uncle Jeffrey Young, who raised White following his mother’s death, placed Young’s Marine Corps hat on his casket. White admired how the marines positively impacted Young’s life, an opportunity White himself could not pursue due to his eventual criminal record, Young said.

“Today is one of the saddest days of my life,” Young later shared through tears. “A person I gave the best of me – not the bad part, but the best of me – seeing him go so young.”

After the burial, over 100 people attended a reception with food and music at Ride Free, located on the basement level at Impact Services. There, friends and family continued to laugh and cry over their favorite stories about White.

Marcel Brown, one of White’s colleagues at Ride Free, shared that even the closest corner store owner knew the date of White’s funeral service. He said the owner brought it up – “Wednesday, right?” – the last time Brown was in the store.

“You can’t keep up with people’s deaths around this jawn,” Brown said. “Papi probably seen them bury 20 young bouls across the street from his store… – so many deaths for him to have been on top of Preme’s burial being Wednesday.”

Nonetheless, the owner told Brown that White was at the store dancing just before he died. He said, “he always looked good – always looked sharp.”

"I said, 'That's Preme,'" Brown said, laughing. "When the Papi store know who you is, that means something."

While there were plenty of stories that captured White’s goofy and outgoing personality, by the end of the day, another clear theme emerged.

It was clear that White is proof of the transformation that can occur when systems are in place to provide positive life opportunities and individuals find it within themselves to pursue them over more accessible options, like selling drugs in the open-air drug market engulfing the neighborhood.

White was born in 1978 at Brookdale Hospital in Brooklyn, New York. His mother died before his first birthday (and her 25th) due to diabetes complications. Doctors amputated one of her legs shortly after White was born. From there, her health rapidly declined.

“His mother said, ‘I’m going to leave you something from me,’ and she left him,” said Young, who, with one of White’s aunts, took White into their home.

“For him to grow up to be the man that he was, he had to go through certain things,” Young said. “He had to go to jail.”

Young and one of White’s aunts took care of White while he was incarcerated. But by the time White was released – Young estimates between three and five years later – his aunt had died. Young was living in North Carolina.

Eventually, after White got off parole in New York, he moved to Philadelphia.

"I seen his transitions through life," said Johns, who met White around 2014, during the service. "I seen him from trapping, to cleaning streets, to impacting the community, to making a whole impact on everybody's life that's here today."

White eventually connected with Impact, a nonprofit that provides various housing, workforce development, and re-entry services. In late 2020, he joined their staff, which Young believes transformed White’s life.

“They was willing to take a chance on him – ‘I’m gonna give you an opportunity to do this and do this, and I’m going to see what you do,’” Young said. “And he showed them, and he even amazed himself.”

Impact then connected White with Luis ‘Lou’ Cruz , the founder of Ride Free, and in early 2022, he joined the Ride Free team – their first employee other than Cruz.

During that time, Young said that White would call him up, bursting with energy and excitement about the work he was doing “for a nonprofit” around the neighborhood.

“He was an outreach person where he was for the community – he was on the street,” Young said. “Boots on the ground.”

In those roles, White proved himself as a uniquely credible messenger for those employed in the drug market and others at risk for getting recruited.

Natasha Santiago said she met White while they were both working on the street. White was sweeping for Impact and eventually doing outreach for Ride Free, and Santiago said she was "doing some things I wasn't supposed to."

"Six-thirty in the morning, every day, I would see that man like, 'Yo, you out here early!'" Santiago said. "Every day, like six to eight months, he would be on my ass like, 'You should come down here – you should see what we got to offer.'"

Eventually, one day, Santiago said it was like “God’s calling.” Something about White’s lived experience and persistence motivated her to meet with Cruz and White to see what Ride Free was about.

“I felt like it was time to make a change,” Santiago said. “I had to right my wrongs.”

Since then, Santiago has worked for Ride Free for two years, where she hopes she’ll be “the next Preme.”

“Like, ‘Damn, if she can do it, I can do it, too,’” Santiago said.

According to Jefe Rodriguez, who White also recruited and now works as Ride Free’s sound engineer, White’s community outreach didn’t stop there.

Every Wednesday at 3:30 p.m., Rodriguez and White would take Ride Free’s recording equipment to McPherson Square Library to help the library staff with the kids. They would give each kid 15 minutes on the mic to get “the shyness out of them.”

“They would be singing cartoon songs, show songs, their favorite songs,” Rodriguez said. “It would just amaze us because some of them would give us conversations like they were grown.”

For Rodriguez, watching White transition from street life to a life devoted to community service is what convinced him that he could do it, too.

“It takes a lot for us men that come from the streets to do that,” Rodriguez said. “So when they actually see somebody that’s a big face outside doing it, it makes people want to put their two cents into it and change – he changed a lot.”

Brown shared a similar sentiment about White’s personal impact on his life. He said that watching White’s transition “from street hustler to community service agent,” not for personal gain but for a genuine “desire to want to change and help people that come from similar backgrounds,” is what made him believe he could change, too.

“Seeing him do it just amplified my reality, that it was for me,” Brown said.

Brown also emphasized that White’s legacy will live on through Ride Free, a movement that White “embodied” built on ability, opportunity, and transformation.

“What Preme’s life really was, was the example of restoring, reviving, and rewriting what the people where we come from story’s supposed to be,” Brown said. “He was an example that it's possible to take the pen and write it back to yourself.”

Meanwhile, Young cautioned the youth who White was working with from letting his death hold them back or bring them down.

“He wants you to succeed – he wants you all to succeed,” Young said. “He does not want y'all to say, ‘I'm gonna give up because he’s gone.’”

The truth of Young’s message was clear based on a conversation that White had about legacy with friend Shantall Polanco, one of the last people he saw before he died.

“He said, ‘I don’t need no kids to have a legacy,” said Polanco, through tears at White's funeral service. “He said, ‘When I die, people are gonna remember me because of all the good deeds that I’ve done; they gonna remember me in these streets – how I was.’”

Free accountability journalism, community news, & local resources delivered weekly to your inbox.