What's happening in Kensington: Week of Jan. 12, 2026

Family Fort Night, MLK Day of Service event and job search assistance.

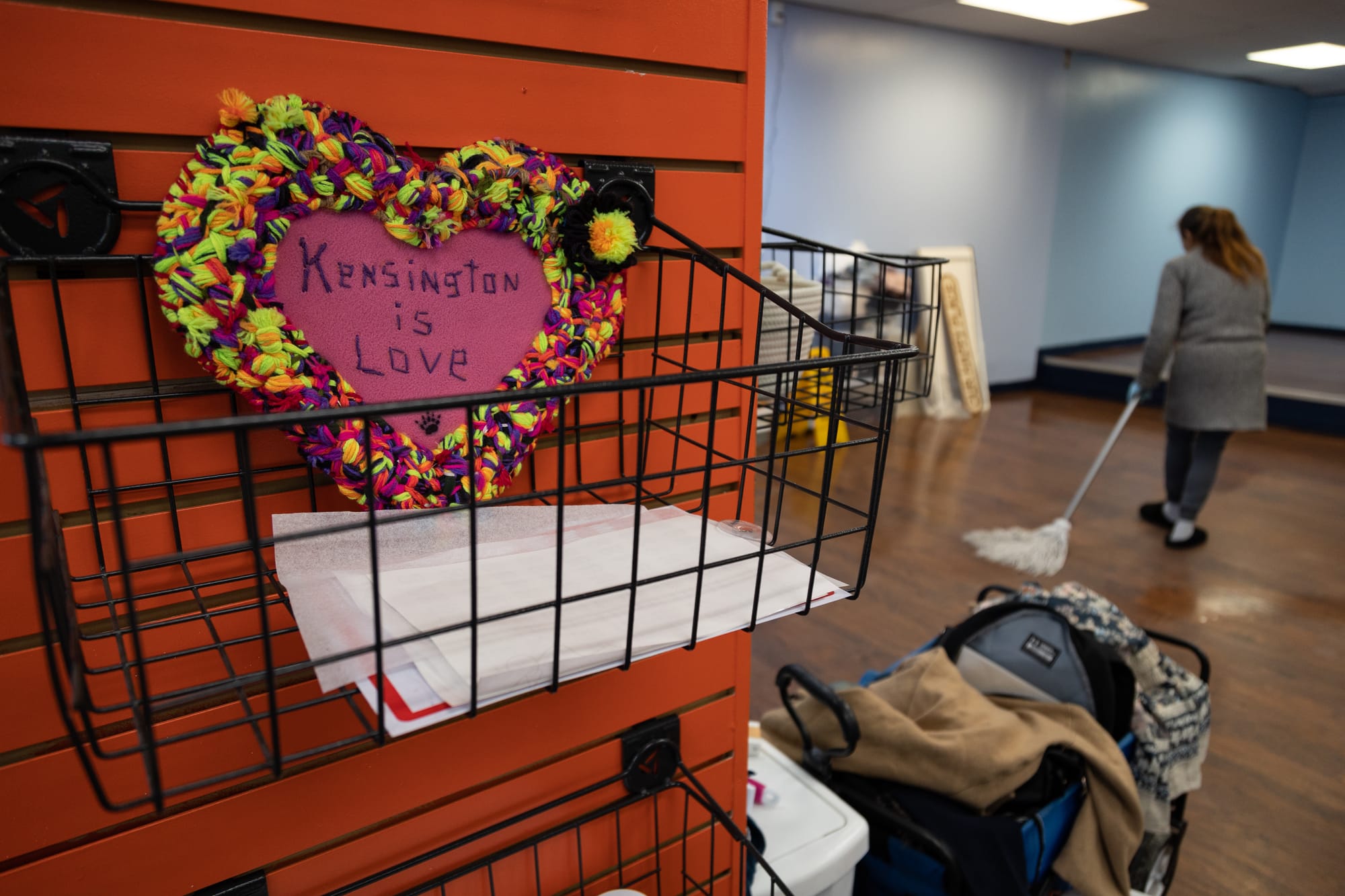

The Sunshine House will offer various services, including gun violence and overdose prevention, and a “messaging center” where people can make and receive calls and collect messages from home.

Late Monday afternoon, several passersby tapped the glass at 2774 Kensington Avenue to share a smile and wave hello.

On the other side of the storefront’s doors, Roz Pichardo, a Kensington resident known by many in the neighborhood as “Mama Sunshine,” was getting organized, running down her list of to-do’s.

“My electric is on, my heat is on, my Verizon internet – because that’s the key – is coming tomorrow,” she said, as a paint sprayer hummed in the background.

In about two weeks, through Pichardo’s organization Operation Save Our City, she is opening a new community outreach and education center called “The Sunshine House,” which she named after individuals living with addiction and the unhoused.

The space will offer various services, including gun violence and overdose prevention, and a “messaging center” where people can make and receive calls and collect messages from home.

“What I’m working on is really connecting the families back with the sunshines,” she said. “Some people who are suffering from active addiction lose hope when they don’t connect with their loved ones.”

But despite Pichardo’s excitement, there is some fear of the unknown.

While she said she’s been working for several years to reopen the original Kensington Storefront space as her own, she admits that opening is hard to discuss without acknowledging the conversations happening at City Hall.

“They’re dividing us,” she said. “It’s us versus them.”

On Feb. 16, the group of City Council members known as “the Kensington caucus” – made up of Quetcy Lozada, Mark Squilla, Mike Driscoll, and Jim Harrity – released a statement calling out neighborhood harm reduction providers as a “nuisance” after “residents and neighboring businesses have explained to us their frustrations with these organizations.”

The statement came the day after the caucus debuted “Kensington caucus” letterman jackets via a video on Lozada’s Instagram page – a post that Pichardo described as “appalling” – and just a couple of weeks after they announced plans to create “triage centers” where people who use drugs are sent to treatment or jail.

“This neighborhood can no longer be the home of an open-air drug market nor organizations that encourage the market to thrive,” the statement read.

The caucus also suggested it was the “overwhelmingly positive feedback about the prospect of certain organizations no longer operating on Kensington Avenue” that drove Shift Capital, a real estate development agency that owns several properties in Kensington and Harrowgate, to terminate the lease for harm reduction nonprofit Savage Sisters Recovery. The same day, Shift Capital confirmed it will not renew their lease when it expires on Sept. 30.

“As we do with all of our spaces as lease expirations approach, we evaluated next steps for 3115 Kensington Avenue. We wanted to provide sufficient notice of this decision to Savage Sisters, so they have time to plan their next steps,” wrote Michael Matera, director of Shift Capital’s marketing, in an emailed statement.

Savage Sisters began doing mobile and street outreach in the neighborhood in 2018 and has provided clothing, food, showers, toiletries, wound care, and housing assistance out of its storefront on Kensington Avenue near Clearfield Street since 2021, according to Executive Director Sarah Laurel, who lives in Kensington. Last year, Savage Sisters reversed 324 overdoses and conducted 172 street cleanups, she said.

“A lot of the neighbors, their outrage is completely justified,” Laurel said. “They absolutely don’t deserve to live in a community that is full of so much blatant trauma. But the only way that we can address that is by delivering public health services, as simple as running water, a shower, a toilet, and a safe space to go in the cold.”

Laurel strongly criticized the argument that Savage Sisters and other harm reduction organizations are to blame for “a decades-long issue” and said the neighborhood’s quality of life conditions “have absolutely nothing to do with harm reduction organizations.” Instead, she blamed the neighborhood’s conditions on “the neglect from City Council, the containment strategy organized by City Council, and the disregard to the drug supply.”

“Nobody is here for a sandwich. Nobody is here to get a free shower. They are here for the drugs – that’s it,” she said. “You can take us away. That’s not going to stop anything that’s happening.”

Mayor Cherelle Parker’s communications team declined to comment on harm reduction in the neighborhood and did not make the mayor available for comment.

“We do not have specifics as yet about what the Parker Administration … plan(s) to do with harm reduction programs and funding in Kensington, since we are currently building strategies in the administration’s 100-Day Action Plan,” city spokesperson Sharon Gallagher wrote in an email.

However, on Feb. 28, Parker gave Lozada a shout-out and offered another glimpse of her administration’s approach to quality of life issues in Kensington at a Chamber of Commerce event.

“For anyone in this audience who thinks that the plan you are going to hear about that we will announce on our 100th day – you’ve heard a little bit about what it will include because you’ve heard us say, ‘Enforce the law,’ and you say to yourself, ‘Well, I think it lacks compassion,’ – I want you to know that the status quo for me in Kensington is unacceptable, that help is on the way, and this is important… we’ll do it with the voices and hopes of the people who actually live in Kensington on our minds first,” Parker said.

But Pichardo, who recently pressed for more information from the Kensington caucus and other city officials about the Kensington caucus’s “triage centers” concept at a Harrowgate Civic meeting, says the crackdown on Savage Sisters is just another example of “vague” communication that’s come from the city since Parker took office in January.

“We’re left blindsided by anything that’s going to happen,” Pichardo said. “And I just don’t think that’s a solution.”

In 2023, both Savage Sisters and their neighbor Stop the Risk – located on another Shift property, about a block away – received $100,000 grants from the Opioid Prevention and Community Healing Fund, launched after the city received a $200 million opioid settlement to distribute over 18 years.

At Stop the Risk, founder Patrice Rogers invites people who are at risk for addiction and homelessness to live in a cluster of tiny homes so long as they abstain from using drugs on the property, help keep the area clean, and look for work.

Even though Rogers does not consider her work “harm reduction,” she says she has reason to believe that Lozada and Shift Capital will scrutinize her organization next. Shift said it is “working with partners to determine next steps” for the property.

“[Lozada] is trying to close down everybody who’s helping people with addiction and homelessness,” Rogers said. “They said they don’t want these people here in Kensington.”

Rogers said the people living at Stop the Risk have helped to clean up the neighborhood. She wants Mayor Parker to see her program and talk to the neighborhood’s community organizations and businesses.

“Why is it that community members are not being brought to the table and having discussions?” Rogers said. “Why is it that one group can make a decision for the whole community?”

Jessica Shoffner, who has lived in Kensington for 16 years and is a board member for Friends of McPherson, shares some of Rogers’s sentiments.

When she first heard that the Kensington caucus was trying to shut down the neighborhood’s harm reduction organizations, she said she felt “really angry” because everyone has been struggling in the neighborhood for a long time.

“The folks who live in houses, the folks who live on the street, the people who work here, people who live here, people who pass through here… we need to consider everyone in the picture, not just a specific population of people,” Shoffner said.

Shoffner said she believes that harm reduction work is “crucial” to solving the challenges everyone faces in the neighborhood.

“Diminishing, reducing, or completely stopping the harm reduction work that’s happening in this neighborhood is going to make what’s happening even worse,” she said. “We are not at a place where we need to continue to be divisive. We need to come together and actually work together.”

However, other Kensington residents have recently voiced strong support for Mayor Parker’s commitment to policing, the Kensington caucus, and the “triage centers” idea, which is not aligned with harm reduction principles.

At recent meetings with the mayor, City Council, and city staff, residents have also expressed gratitude to elected and city officials for committing to policy shifts and enforcement that give them hope.

Meanwhile, other residents have shared their anti-harm reduction views with City Council. For example, on Feb. 8, resident Crystal Anderson testified at a City Council meeting that she believes providing people who use drugs with things like crack pipes, condoms, sterile needles, and wound care “keeps them sick.”

“Where’s the tough love?” she said.

Previously, other residents testified in support of the safe injection site ban, which City Council passed in nearly every city district.

“We cannot walk the streets without seeing uncapped needles,” said Harrowgate resident Lucia DiMascia at a September City Council meeting. “Children [are] watching this in their developmental years and thinking that it’s normal.”

Pichardo says these are misconceptions.

“Their misconception is that harm reductionists are enabling – that we need to let people hit rock bottom,” she said. “There’s no such thing as rock bottom.”

She also warns about the dangers of taking away evidence-based tools for disease prevention, such as syringe service programs, which research has repeatedly shown to decrease disease without increasing injection drug use.

“We as a society have to make sure that people are safe, that they’re not transmitting diseases by sharing syringes, and that they’re not getting hepatitis so we don’t have another outbreak,” she said.

Since the Kensington caucus released its statement about harm reduction providers in the neighborhood, Savage Sisters and Prevention Point – the neighborhood’s largest harm reduction provider – have said they will continue their work in the community.

Prevention Point, which began its syringe services at the height of the AIDS epidemic in 1991, wrote in a statement they have “no plans to leave Kensington” and that their leases in four different locations “are all secure.”

“Prevention Point is a part of the Kensington community, and we care about it, deeply,” the statement read.

Meanwhile, since the Savage Sisters knew their lease was at risk, Laurel said they raised enough money in advance to renovate two new vans with showers and wound care stations for their mobile outreach. Now, they are raising more money to support their mobile distribution needs.

“I told my board a year ago, ‘We’ll see if we can renew the lease, and if we can’t, we go mobile,’” she said. “We go where our friends go, you’re not going to stop us from serving our community.”

People who use drugs in Kensington said without organizations that distribute sterile needles and provide wound care, such as Savage Sisters, rates of disease and death will inevitably increase.

“If they got rid of this place and all the resources they have, it would just get really bad,” said one man, whose name was withheld for privacy reasons, who visits Prevention Point regularly. “A lot of these people, that’s all they have.”

For Pichardo, it’s important that city leaders hear from the people directly affected and understand the potential impact of their decisions to remove certain services.

“This is a crisis we're in,” she said. “We’re fighting for people’s lives.”

*Reporters Khysir Carter and Sammy Caiola contributed to this story.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.

Free accountability journalism, community news, & local resources delivered weekly to your inbox.