Philadelphia City Council’s Special Committee on Kensington is pressing top city officials on the effectiveness and cost of the city’s diversion programs, which aim to keep low-level offenders, including those arrested for drug-related offenses, out of jail.

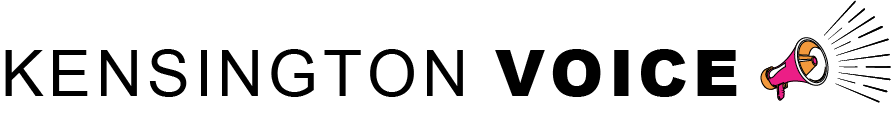

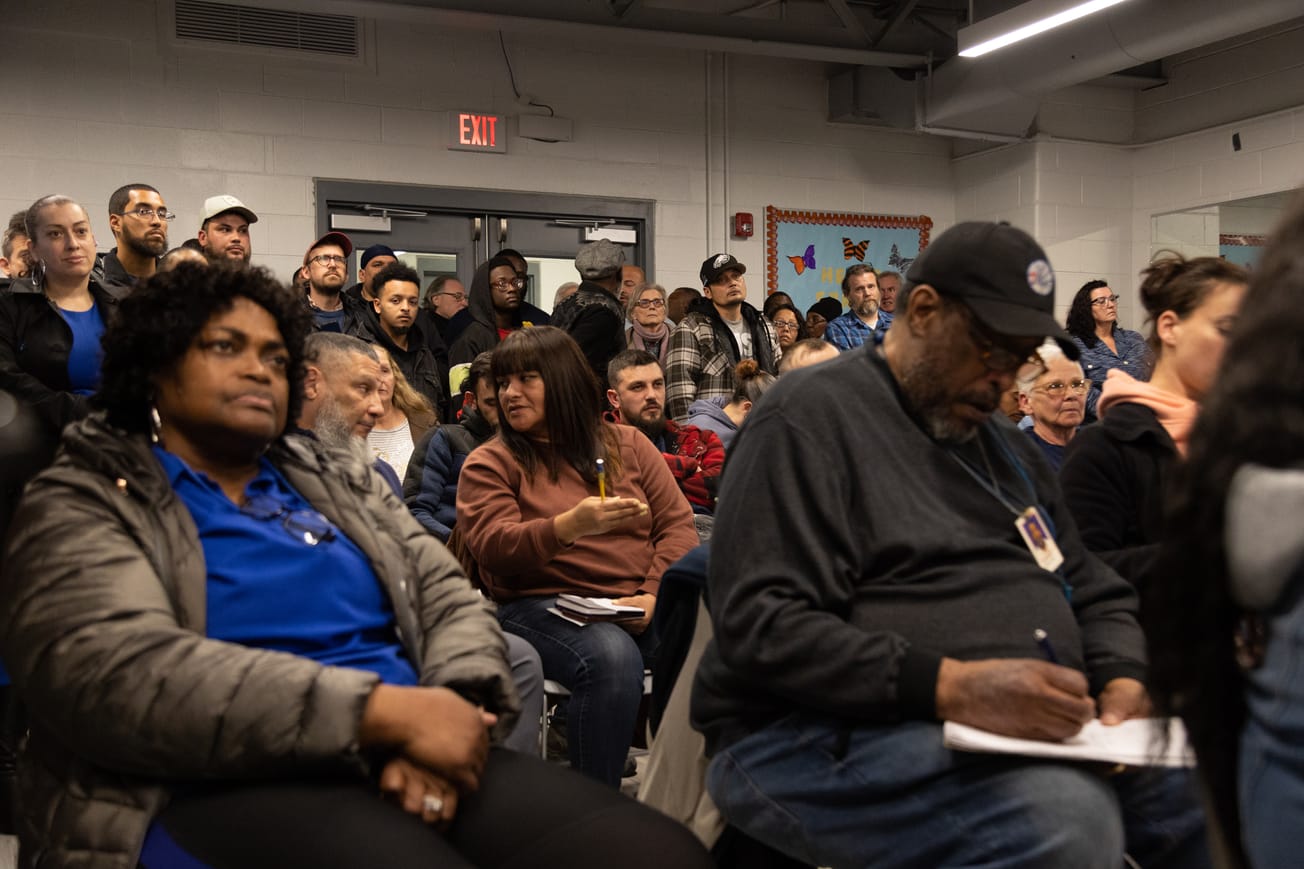

During a five-hour hearing on Wednesday, the committee—which includes council members Curtis Jones, Nina Ahmad, Mark Squilla, Mike Driscoll, and Jim Harrity—heard testimony from city officials involved in the city’s various diversion programs.

The committee wanted to know three things: how the city-funded programs are spending their money, how effective those programs have been, and whether they “need to pivot to something else,” according to Ahmad.

“At the end of the day, these are tax dollars,” Ahmad said. “We are putting so many resources into one disease, [but] we have multiple other problems in this city.”

Balancing accountability and diversion

District Attorney Larry Krasner opened his testimony by highlighting the number of “shooting gangs,” firearm dealers, and drug rings that prosecutors have dismantled in recent months.

“We really can’t talk about diversion unless we contextualize it with accountability,” Krasner said. “There is a difference between the disease of addiction and people who hurt people.”

Both Krasner and Chief Public Safety Director Adam Geer explained that diversion programs provide an alternative pathway for people with substance use disorders, helping them avoid lifelong barriers to housing and employment while also reducing recidivism.

“We all want safety,” Krasner said. “We all want people who are not living or dying on the street. We don’t want to have three to four people dying of fatal overdose a day.”

According to city data, about 10 percent of those who go through the city’s Police-Assisted Diversion (PAD) program once are diverted again. About 1.5 percent of PAD referrals are referred a third time, Geer said.

“The story of those numbers is clear,” Geer said. “People who get into PAD overwhelmingly stay off the streets of Kensington.”

How the diversion programs fit together

In Kensington, when someone is arrested for a low-level offense like disorderly conduct or public intoxication, police are supposed to take them to the PAD office on Lehigh Avenue. The building also houses part of the new Kensington Wellness Court, which launched on Jan. 21 and operates on Wednesdays.

Geer described the office as a social services hub rather than a traditional law enforcement facility.

“If we can treat people with dignity, if we can offer quality help, and if we can build accountability into the process, we can and we will succeed,” he said.

When Wellness Court is available, people who receive medical clearance are checked for outstanding warrants. If they do not have any warrants or a judge is willing to clear them, they can continue through the Wellness Court process.

But those with warrants that can’t be cleared are taken to jail, which can be deadly.

Chief Defender Keisha Hudson, of the Defender Association, said Philadelphia’s jails are not equipped to handle complicated and dangerous withdrawal cases.

“We lost two clients, in addition to Amanda Cahill, in the last year because of bench warrant detainer issues,” Hudson said. “The jail just was not prepared to treat this population.”

Deputy Police Commissioner Fran Healy acknowledged the system’s flaws.

“When somebody has serious warrants on them, there’s not much we can do,” Healy said. “We can prepare prisons for the receipt, and do everything we need to do, but we need to make sure the low-level individuals don’t end up in that.”

Geer said the city has launched a pilot program that uses bracelets to monitor the health of incarcerated people who are suspected of using drugs. Further details about the program were not shared.

For those who do not go to jail, the next step in the process is a choice: accept city services (such as addiction treatment) or stand trial (which could result in fines if found guilty), according to the executive order that enacted the program.

When Wellness Court is not in session, the PAD office also offers a pre-booking diversion program for people arrested for certain low-level offenses. The program operates Monday through Friday from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m. To qualify, participants cannot have existing warrants and may only be diverted to PAD twice. If they are arrested for a PAD-eligible offense a third time, they are booked and go through the standard charging process.

Beyond the PAD office’s programs, the District Attorney’s Office (DAO) offers the Accelerated Misdemeanor Program, commonly called AMP Court, which allows people arrested for certain nonviolent offenses to avoid trial by completing community service or drug treatment.

Those with substance use disorder facing higher-level charges are able to enter Drug Treatment Court, a yearlong program separate from AMP Court.

According to Kayla Arnold, the DAO’s adult diversion program supervisor, 93 percent of graduates successfully stay out of the city’s criminal justice system— a massive change compared to the recidivism rate of those who entered prison on similar charges.

Diversion limitations, opportunities for expansion

At Wednesday’s hearing, several people testified about the limitations of the existing diversion system, particularly in terms of accessibility and capacity. Expanding and accelerating access to addiction treatment was a key concern.

“The faster we can get them that withdrawal management, frankly, the faster we can stabilize them, the better their headspace, and the healthier they’ll be as they go on the first steps in their journey,” Geer said.

Arnold emphasized the importance of meeting people’s immediate, basic needs, such as stable, long-term housing— a concern shared across city departments.

Research supports Arnold’s concerns. A 2021 study on PAD found “a mismatch between services that PAD advertises and services that PAD provides,” particularly in securing housing for participants.

Hudson advocated for additional funding to hire more social workers within the Defender Association, saying they could help remove key barriers to recovery. Since social workers are responsible for following people through social service networks, they could also help the city better understand program outcomes, she said.

Dr. Evan Anderson, a diversion programs researcher at Thomas Jefferson University, emphasized the importance of keeping those impacted by these policies at the center of the conversation.

“Any system has to put the humanity of people first,” Anderson said. “We have to keep talking to people, and asking why does this program work for you or not work for you? Right? And that’s hard. It’s really hard work, but it’s really important.”

The committee called a panel of people with lived experience with addiction.

Among the most personal testimonies came from Raquel McNichols, who participated in AMP Court and the Forensic Intensive Recovery (FIR) program.

McNichols testified that she started drinking alcohol at age 12, using Percocet at 15, and eventually became addicted to heroin at 25.

After experiencing homelessness and several arrests for drug possession, she went to treatment through AMP and stopped using drugs and alcohol.

Then, as is common for people with substance use disorders, she started using drugs again. Eventually, she was arrested for robbing a bank.

“I needed money to get high, and that was my only motive,” she said. “I did not want to hurt anyone.”

In prison, she said she entered treatment and enrolled in the FIR program. She credits the experience, particularly the therapeutic services FIR offered during and after her incarceration, for her continued sobriety to this day.

While Wellness Court is less than two months old, during Wednesday’s hearing, the Kensington committee members pressed panelists for clear measures of success.

Specifically, they wanted to know how programs could be streamlined or consolidated, particularly to cut costs amid financial uncertainty.

But measuring the success of the Wellness Court is complicated because so many programs are involved in the diversion process, Anderson said.

Anderson explained that while the cost of running diversion programs is precise and specific, the benefits come in a number of ways. He suggested one possible success metric: looking at how much money was saved on healthcare or incarceration costs.

And, although Council members pressed Anderson on which programs were falling short, he offered a different solution: expansion.

“The ultimate effect of our diversion programs will be contingent on our ability to provide accessible, high-quality resources and care,” Anderson said. “It is not easy, but the model is being built in Philadelphia.”