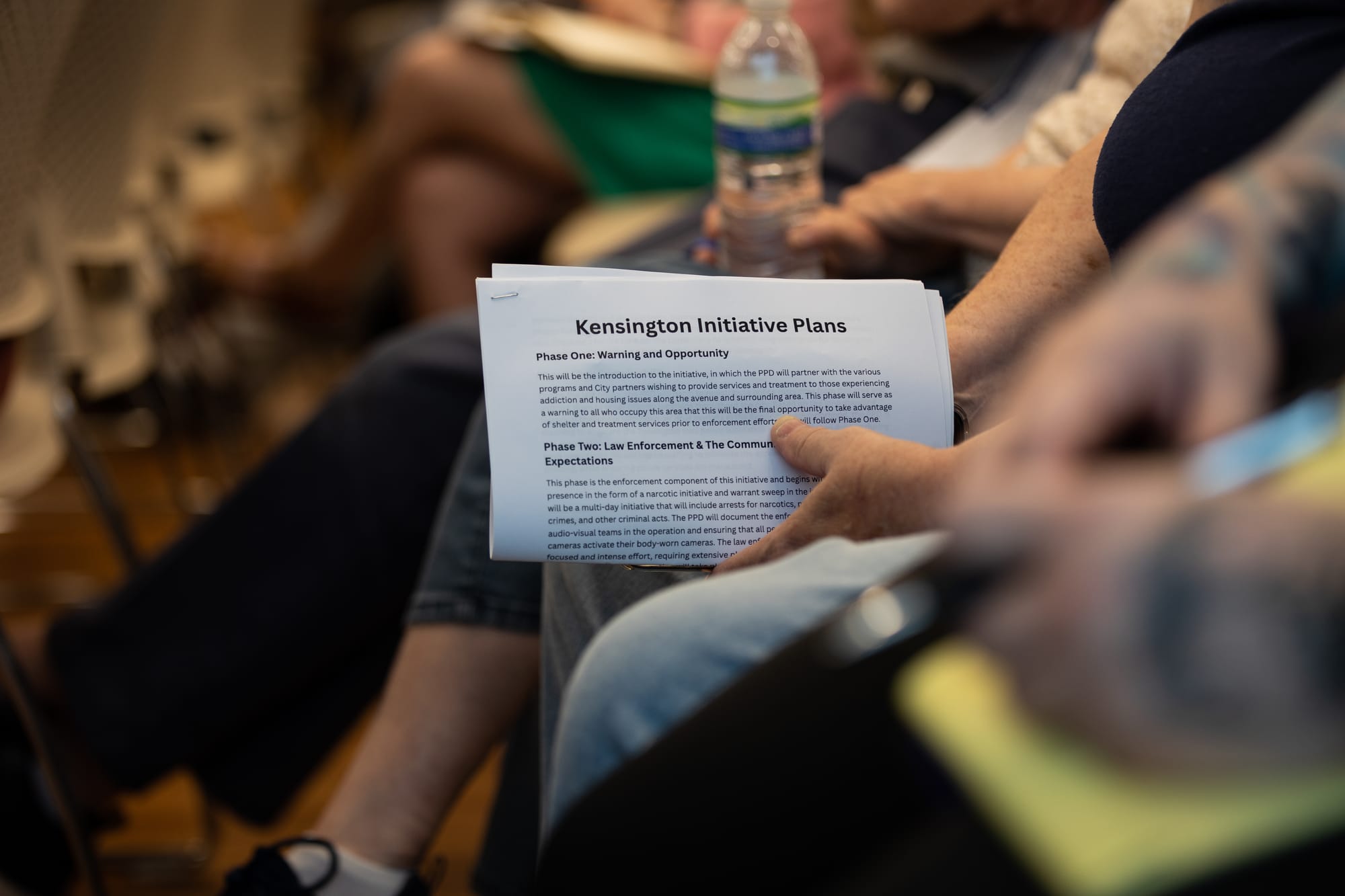

Following an encampment sweep on the 3000 and 3100 blocks of Kensington Avenue Wednesday, police have flooded the area, leading residents and activists to wonder when a law enforcement crackdown is coming – especially as the Philadelphia Police Department moves forward with Mayor Cherelle Parker’s Kensington Community Revival plan.

The five-phase initiative starts with “warning and opportunity,” which police commissioner Kevin Bethel said would officially begin shortly after Wednesday’s encampment sweep. The next phase is “law enforcement and community’s establishment of goals and expectations,” which Bethel has said will entail more aggressive police action.

PPD representatives confirmed that the department has “allocated resources to the area to maintain the former encampment site clear."

“Officers are to respond to calls for service in the area and ensure that encampments don't pop back up,” said Corporal Jasmine Reilly in a statement.

The city had promised to transport individuals to shelters, treatment facilities and other service locations Wednesday. But when police arrived early that morning, outreach workers were not on site.

No arrests were made, according to the police department. However, police began setting up barricades at 5:30 a.m. and sanitation workers threw out people’s tents, causing people to scatter to surrounding blocks before having the opportunity to receive services.

The Citizens Police Oversight Commission (CPOC) – a city agency created to monitor police misconduct –said Thursday that they’ll perform an “after action review” based on accounts from two of their members who were present Wednesday. They’re also welcoming feedback from members of the public who witnessed the encampment resolution.

“(CPOC) shares the community’s profound concern regarding the recent dismantling of the Kensington Homeless Encampment in Philadelphia,” the statement reads. “In light of the community concerns and public need to achieve a thoughtful understanding of the operation, CPOC will conduct an after action review.”

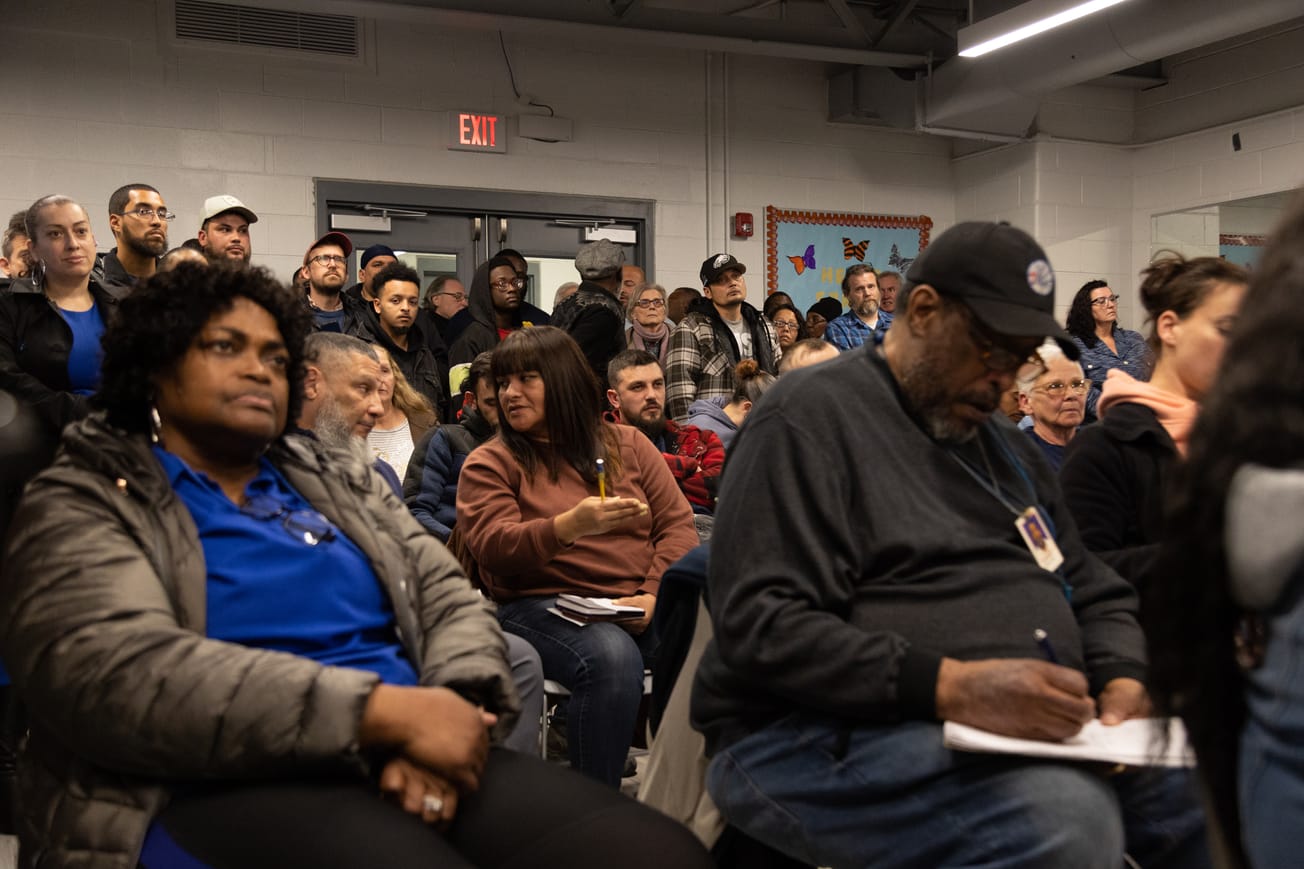

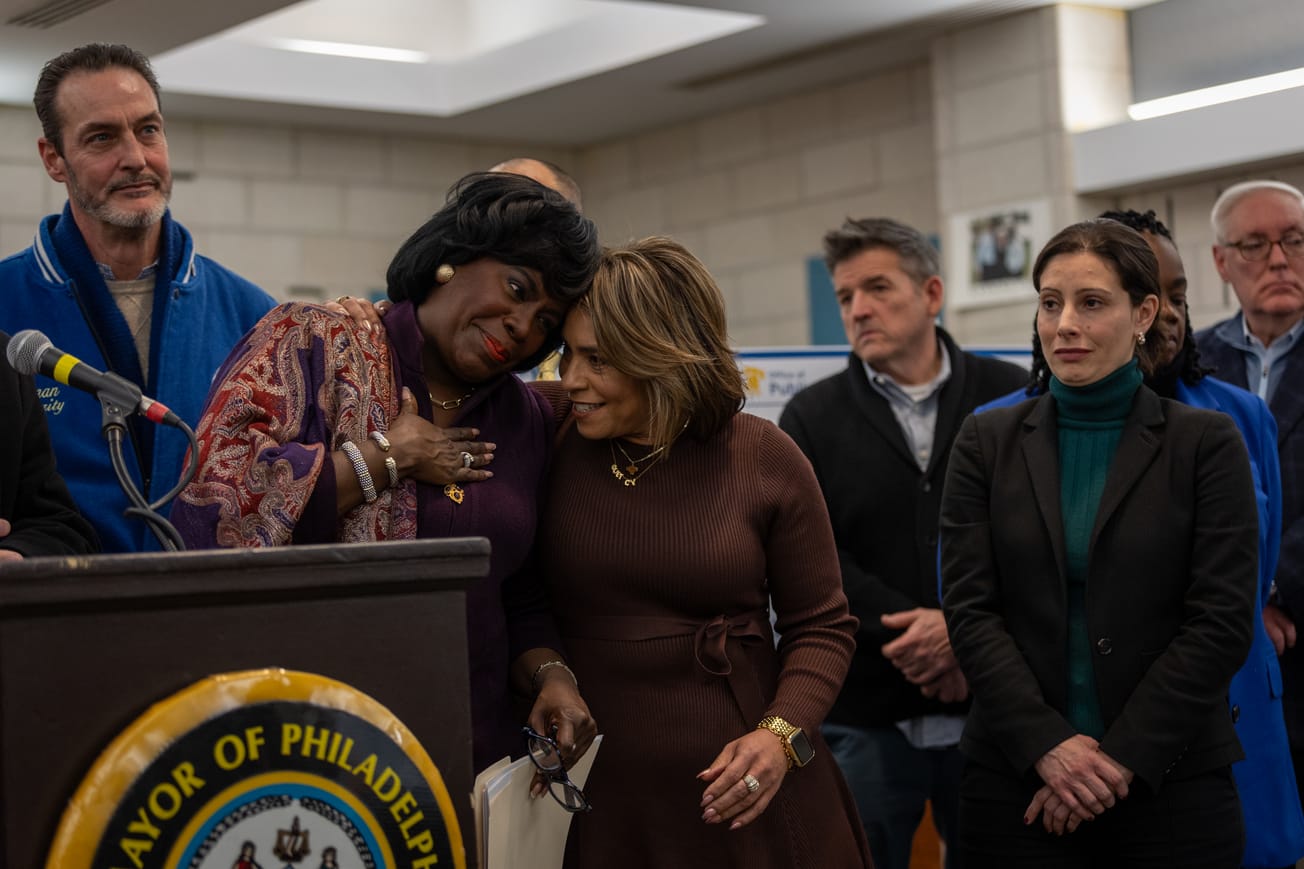

Mayor Parker laid out her long-term plans for Kensington during a packed May 7 budget talk at Rock Ministries on Kensington Avenue. The city has recently leaned into its partnership with Rock Ministries, which connects people to Christian addiction treatment programs up and down the east coast.

Parker spoke Tuesday about shutting down the drug trade in Kensington and said she’s “proud we have a police department that has put together a comprehensive plan to address it.”

She said that she expected there to be some arrests during the Wednesday encampment resolution, contrary to a PPD spokesperson’s Tuesday afternoon statement that the encampment sweep was “not an enforcement event.”

“Will some people be arrested? I don't have a crystal ball, but I can tell you that I think so,” Parker said. “There will be some people, but that is not the goal. The goal is to connect people to services.”

The Defender Association of Philadelphia, made up of the city’s public defenders, said in a statement hours after the sweep that the event “signals a return to draconian and ineffective crime and drug policies.”

“The unintended harms of the planned ‘jail vs. treatment’ strategy outweigh any derived benefits for people in addiction,” the statement reads. “The city’s actions also threaten to overwhelm the court and jail system, and will likely shift the current problem to other neighborhoods.”

‘We were not directly involved’

Defender Association representatives also say there was a “lack of communication” from the city in advance of Wednesday’s action.

District Attorney Larry Krasner echoed that statement in an April 19 interview with Kensington Voice, calling communication around the Kensington Community Revival plan “vague.”

“We were not directly involved in the plan that Mayor Parker released,” he said, noting that he had only met with Parker in-person one time.

Police leaders have said they will target people who sell, use and possess drugs in Kensington.

Krasner said his office does charge those cases, but aims to divert people into the Accelerated Misdemeanor Program instead of incarcerating them.

His 2021 book, “For the People,” includes a chapter on approaches to the opioid crisis in Kensington titled “Do Less Harm.”

The chapter includes arguments in support of clean needle exchange programs and “harm reduction sites,” known more commonly as supervised injection sites. The city banned these sites from all but one City Council district last fall, and the Parker administration has stated that they will no longer fund needle exchange. Krasner also details the increased risk of HIV and Hepatitis C spread when such resources are not available, a concern that public health experts have echoed since Parker took office.

“Arguably, no area of criminal justice policy has been more flawed than America’s punitive, prohibitionist approach to the use of drugs,” Krasner writes. “For the people harmed, there is little difference between government attacking them and government standing by while disease attacks.”

He said his office generally does not prosecute possession of marijuana and buprenorphine, or prostitution.

“We’re the ones who have to judge whether there’s probable cause, whether we think it is just or not just to bring a case,” he said. “Not knowing who’s going to get arrested under what circumstances for what or how, we don’t have a decision to make unless or until someone presents us with an arrest.”

There’s one loophole, though. Police can charge certain crimes themselves without involving the District Attorney’s Office using the protocol for “summary citations.”

Loitering, disorderly conduct, harassment, and low-level retail theft are all summary offenses, according to nonprofit organization Community Legal Services.

Police cannot take someone into custody for a summary citation unless they have an existing warrant, according to police department directives. People are cited and then generally expected to pay a fine or show up in court.

Mike Lee, executive director of the ACLU of PA, said many “quality of life” crimes fall under the summary offense umbrella. When he served in the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office, he ran the summary offense courtroom. Public defenders don't provide legal representation for summary offenses, he said.

“It was really a difficult room to run because most people wouldn't show up,” he said. “Because they were unhoused people who might not even know they had a court date.”

Drug paraphernalia arrests are up

Arrests for carrying drug paraphernalia are on the rise, according to Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office data. Between June of 2022 and November of 2023 there were fewer than five charges related to drug paraphernalia per month. That number climbed to 15 in December of last year and 34 in January. There were between 5 and 10 charges monthly in February and March.

Krasner told Kensington Voice he has noticed the change.

“We've had very, very few arrests for this until just recently,” he said. “We are looking at these new trends that we're seeing, and we are figuring out what to do about them.”

When asked whether he knew of any changes in law enforcement strategy in regard to paraphernalia, Krasner said “no comment.”

Pennsylvania law defines paraphernalia as items “for the purpose of … storing, containing, concealing, injecting, ingesting, inhaling or otherwise introducing into the human body a controlled substance.” Examples include drug testing tools, scales, bowls or blenders, syringes and pipes.

People who use drugs in Kensington sometimes carry a card containing the text of Executive Order (4-92), an Ed Rendell-era policy that legally protects people carrying clean needles from arrest. Harm reduction activists said they’ve heard about more people being arrested for carrying unused needles, even while carrying the card.

Between January and late March, arrests for drug possession were up 31% compared to the same period the year prior according to District Attorney’s Office data. The 24th and 25th districts see the bulk of all arrests citywide.

Meg Jones, a Kensington resident who works for a Philadelphia legal aid organization, raised this trend at a late April community meeting at Esperanza’s CORE wellness center with the Citizens Police Oversight Commission.

“With increased emphasis on charges for prostitution, charges for possession, how [are] people supposed to know all of a sudden that these changes are going to occur?” she asked. “What community education is going to take place?”

No one from the commission or from the city’s Managing Director’s Office was able to answer Jones’s question. Representatives from the Philadelphia Police Department were not in attendance.

At Rock Ministries on Tuesday, Parker vowed to make future appearances in Kensington and answer peoples’ questions about public safety.

“You deserve to know, and every chance I get to come and see you and talk to you, I'm gonna get it done,” she said. “We're going to do the best we can with what little we have to change the trajectory of this community and I can't do it without police.”

Stops and searches

During the Wednesday encampment sweep, Kensington Voice witnessed SEPTA police officers handcuffing a Black man outside the Kensington and Allegheny station. Officers then removed his jacket, unbuckled his belt, and pulled his jeans down to the ground. They searched the pockets of the gym shorts he was wearing underneath his jeans, and shined a flashlight inside the shorts. The man was slumping over and nodding off during the search.

A SEPTA spokesperson later confirmed the charge was possession of drug paraphernalia.

Philadelphia has a long history of aggressively policing Black and Brown residents, especially during the Frank Rizzo era. In 2011 the city settled a class-action lawsuit with a group of Black and Latino men who were stopped and frisked unconstitutionally, arguing that police at the time were disproportionately stopping and searching this population. The settlement is sometimes called the Bailey Agreement.

To comply with the terms of that settlement, police had to launch a pilot program in 2021 that prohibits formal stops for certain quality of life crimes including open alcohol containers, public marijuana smoking, noise complaints, and disorderly conduct. That program is now in place citywide.

David Rudovsky, one of the prosecutors on the Bailey case, said his office is going to be “looking very carefully” at whether or not police stops under Mayor Parker would violate the agreement.

“The way they’re trying to package it, it’s not just the old-style policing,” he said of Parker’s plans. “It’s a little more nuanced, but we don’t know how much more.”

Regarding the incident with SEPTA police Wednesday, Rudovsky said the officers were legally allowed to search that man because he was under arrest.

“Putting aside the question of why we would arrest someone for that minor offense, police are allowed to do a full search,” he said. “Taking his pants down in public seems unnecessary to me, but I cannot say it violates the Fourth Amendment.”

Also under the agreement, police must document all stops and the motivations behind them in a database. Vehicle and pedestrian encounters have been gradually rising since November 2023. Police made nearly 14,000 stops in February 2024 - the highest count in about three years. Since 2014, Black Philadelphians have been the subject of 69% of stops, though they make up just 40% of the city’s population.

Individuals don’t have to show identification to police officers unless they are under arrest, or in some cases if they are detained for a stop based on reasonable suspicion, according to Rudovsky.

Activist and Kensington resident Yahaira Galarza, a former community ambassador with the ACLU, said she’s been trying to spread the word about how people should conduct themselves if stopped by police.

“Never argue with the officer no matter, because they are law enforcement,” she said. “They are in power, so it's going to escalate.”

Reporting police misconduct

Any agencies or groups who witnessed or observed the encampment sweep that want to share their perspective on the police presence, or anyone who experienced or witnessed police misconduct during the event, can reach out to the Citizens Police Oversight Commission by contacting 215-685-0891 or cpoc@phila.gov to file a complaint.

There are also multiple ways to file a complaint about a police officer when someone feels their rights have been violated.

Per the Defender Association of Philadelphia website:

- The Philadelphia Police Department (PPD) Internal Affairs Division accepts complaints online through their Official Complaint Form.

- PPD has a one-page Official Citizen’s Complaint Form which may be given in-person at any police district, any City Council office, any Neighborhood Advisory Centers, the Mayor’s office for Community Services, the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations, or PPD Internal Affairs.

- The City of Philadelphia Citizens Police Oversight Commission (CPOC) accepts complaints against Philadelphia police officers and sends them to the Philadelphia Police Department Internal Affairs Division. CPOC serves as an impartial intermediary and accepts complaints online, via email, mail, or in person. See details here.

Additional resources:

- To file a complaint with the ACLU of Pennsylvania fill out this online form.

- Legal observers or protesters who are arrested can call the Up Against the Law Arrest Hotline at 484-758-0399

*Emily Rizzo contributed reporting to this story

Editor's note: This story was updated on May 10 to include more context about the SEPTA arrest incident.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.