Conwell Middle School will no longer close, Philly school district says

The decision to spare the two schools from proposed closures comes after nearly a month of intense community pushback against the district’s sweeping facilities plan.

For many Kensington residents, the cycle of the city clearing encampments with people experiencing homelessness and those encampments moving to another stretch of the neighborhood weeks later has taken a toll.

“I use the phrase ‘death by 1,000 cuts,’” said Harrowgate resident Alfred Klosterman. “You go out in the morning just to see what’s been stolen from your porch, or you have to sweep the needles off of your step every day, or when you’re walking up to catch the bus, you have to watch that you don’t step in feces.”

At a public City Council hearing on August 11, Tumar Alexander, the city’s managing director, said the city plans to clear the encampments again on August 18. Now, Kensington community members — including those with and without housing — wonder how the city will handle the situation differently this time around.

Klosterman, who is also a member of the Harrowgate Civic Association, said the situation in the neighborhood has not improved since 2017 — when he first remembers public drug use, encampments, and street homelessness increasing in the neighborhood.

“Trying to resolve this situation, in a lower-income neighborhood, is just really rough,” Klosterman said. “There is no resolution in sight. I mean, regardless of what anyone in the city says — it’s hard to picture that they do have an endgame.”

The city will begin clearing the encampments at 9 a.m. on August 18, according to an email from a city spokesperson. They plan to start with the 3200 block of Kensington Avenue near the intersection of Allegheny Avenue, followed by the 1800-2000 blocks of Lehigh Avenue between Kensington Avenue and Emerald Street.

As of August 17, the city had arranged 23 placements into low-demand housing and treatment programs for people living in the encampments, the spokesperson said. The spokesperson said it is difficult to estimate how many people are living in the encampments due to the “fluid movement of people in and out of these spaces.” However, they said that the city’s most recent list of individuals experiencing homelessness included approximately 50 people’s names from the 3200 block of Kensington Avenue and the 1800 block of Lehigh Avenue.

Currently, the city is working with 10 organizations to provide shelter and treatment beds across the city, and there is room between the addiction treatment and shelter systems for everyone in the two encampments, the city spokesperson said. The City could not confirm the total number of available beds at the time of publication.

Over the last month, the city’s Street Outreach teams have engaged with people living in the encampments and on the streets across the neighborhood to offer them treatment, medical care, shelter, and stranded traveler assistance to go home, the city spokesperson said. The city spokesperson also listed the city’s efforts in regard to the Opioid Response Unit addressing the quality of life in the neighborhood.

“At the same time, we recognize that there is a long way to go and we continue to listen to residents to help guide our efforts,” the spokesperson wrote in an email to Kensington Voice.

Read more: 2021 Opioid Response Unit Action Plan: Here are the solutions the city will implement in Kensington

Like housed community members in Kensington, those without housing and some with a substance use disorder, have said that they also feel that the systems of recovery and housing could be improved.

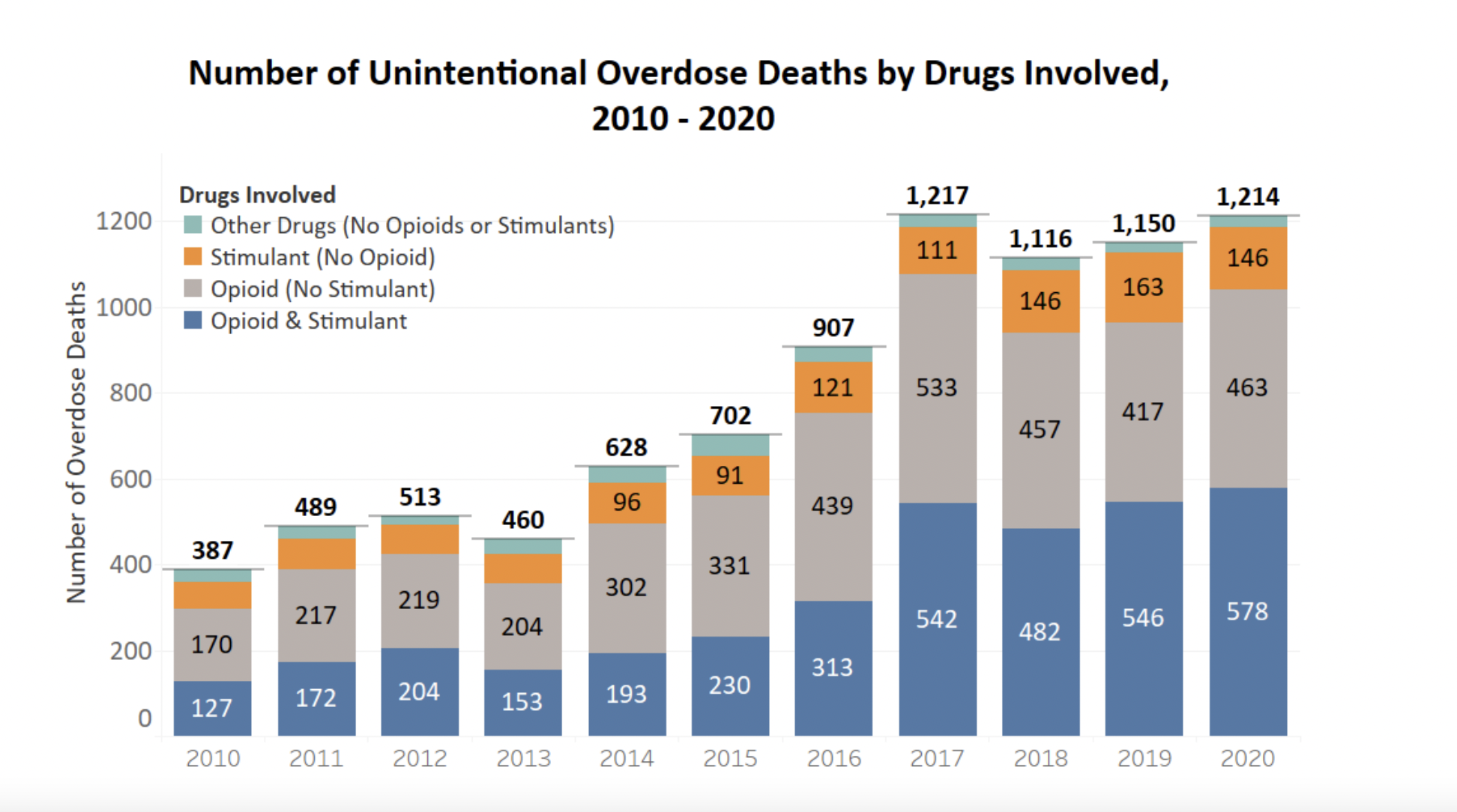

Although encampments with people experiencing homelessness are nothing new to Philadelphia, in Kensington, a former manufacturing leader of the East Coast throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, encampments weren’t always a part of the working-class neighborhood. According to Billy Penn, it wasn’t until the mid-2010s when the city’s drug overdoses sharply increased that Kensington became home to the most people experiencing street homelessness in the city. Since then, encampments have become a defining characteristic of the neighborhood.

During the last few years, the Kenney administration has enacted several programs to address behavioral health, mental health, and housing issues in the neighborhood. First, the administration created the Mayor’s Opioid Task Force, then the Encampment Resolution Pilot and the Philadelphia Resilience Project, and now the Opioid Response Unit (ORU). The ORU focuses on engaging people experiencing homelessness and those with a substance use disorder in the city.

Since 2018, the City has used a model for clearing encampments known as the Encampment Resolution Program (ERP) — a program that initially started in the Kensington neighborhood as a pilot initiative. According to the City, the ERP is a social-service-led initiative made up of a network of service providers, outreach teams, and medical workers who go to encampment clearings and connect unhoused people to behavioral and mental health treatment and other social services.

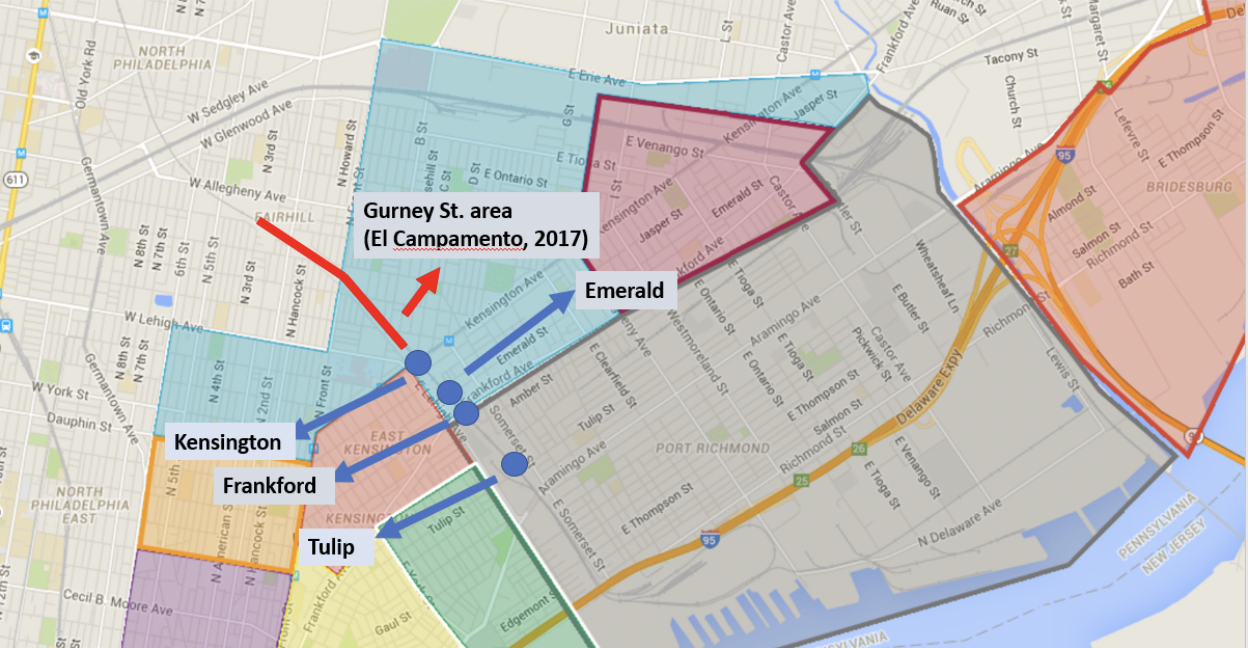

A year before the ERP pilot started, the City cleared an encampment along a Conrail rail line in Fairhill, known as “El Campamento,” and received criticism for its limited strategy for relocating people who were living there. According to Stephen Metraux, a researcher who studied the Kenney administration’s encampment resolution pilot program in 2018, the City tried to improve its approach with the development of the ERP.

“The City basically set out to say, ‘We’re going to do this right this time.’ They got a committee together, and they looked at other cities and how they were addressing the problem,” Metraux said.

For the development of the ERP, the Kenney administration focused on San Francisco where City officials were clearing encampments while providing services, Metraux added. Metraux, who is the director of the Center for Community Research & Service at the University of Delaware, worked with researchers at the University of Pennsylvania to analyze the impact of the pilot program.

According to the researchers’ report, which was published in 2019, 72 (38%) of the 189 people who were engaged during the ERP pilot were connected to short-term housing or addiction treatment programs. The ERP also connected an additional 36 people to long-term housing or recovery arrangements. In total, nearly 60% of the people living in encampments during the ERP pilot in June 2018 interacted with outreach workers and had a direct opportunity to engage in city services.

In the report, Liz Hersh, the director of the Office of Homeless Services (OHS), noted that people in recovery don’t often have a “Point A to Point B” path to recovery, and that it’s more of an “ebb and flow” of engagement with services. Therefore, because of the ERP’s ability to provide available short-term resources on-site at encampments and create relationships with people who may be ready to receive services down the line, the researchers considered the ERP, in part, successful in achieving those goals. For example, by early 2019, an additional 12 people who initially engaged with the ERP pilot in 2018 were connected to short-term housing and treatment services.

However, once individuals stabilized in short-term housing and treatment services, they joined an even larger group of people waiting for placement into the limited supply of long-term and permanent housing across the city, Metraux said.

“It worked out well in that they set up the detox centers, set up the rehab, they set up the temporary shelter facilities — and most of those arrangements lasted 45, maybe 60 days,” Metraux said. “Then the quest to keep people going along that trajectory, they needed to have longer term facilities, recovery houses, and more permanent housing or something that’s going to get them stabilized on a longer term basis. And those services simply are not there in the city.”

Since the City’s initial Conrail encampment cleanup in 2017, the City has evolved the network of service providers and resources, according to Eva Gladstein, the deputy managing director of the City’s Health and Human Services who oversees parts of the ERP. For example, the City helped Prevention Point offer more shelter beds to create easier transitions into temporary housing for people living in the encampments and has continued to track individuals’ progress through their recovery, Gladstein said.

Additionally, the Office of Homeless Services (OHS) has focused on simplifying the transition from temporary to permanent housing with pilot initiatives, such as the Rapid Re-Housing Program. The Rapid Re-Housing Program allows households and individuals to receive rental assistance and wraparound services for up to two years, without having to enter a shelter first. These efforts are also intended to address how encampments have changed over the last several years, Gladstein said.

“Groupings are much more fluid now,” Gladstein said. “People kind of move around, and they’re often going to buy drugs or to use drugs to be in company with other people who they feel are part of their community. They’re not permanently bedded down in one spot.”

During the ERP pilot, the City cleared two of the four encampments that were located beneath underpasses that connect Lehigh Avenue to Somerset Street — the Kensington Avenue and Tulip Street sites. Three of those four encampments appeared after the City cleared the encampment near the Conrail line in 2017. Now, the encampments have moved north toward Somerset Street, Allegheny Avenue, and McPherson Square. According to interviews with people experiencing homelessness during the 2018 ERP pilot, published in Metraux and his colleagues’ report, some expected this would happen.

“They felt that homelessness would continue to exist in Kensington, but it would move to other places in the neighborhood, including the other camps, abandoned properties, and the steps of the transit station,” the report stated.

Now, some community members believe that history will repeat itself if the City uses the same approach.

“All we’re doing is moving people back and forth,” Klosterman said. “It’s not as if there’s a large building that they’re going to put them in and give them treatment. Everything just seems to be, ‘Well, let’s do this for the time being.’”

Without increasing long-term and permanent housing opportunities in the city, Metraux expects that the encampments in Kensington and Philadelphia will continue.

“These are just structural elements that go beyond Kensington. I mean, they could conceivably clear encampments out of Kensington, but it’s going to happen somewhere else,” said Metraux, who has been researching homelessness for the last two decades.

According to Mike Hinson, the president of one of the city’s largest providers of emergency housing SELF Inc., the city’s housing and treatment systems need to be improved, and homelessness can’t be solved by only increasing housing. At SELF Inc., Hinson guides the agency’s efforts in emergency and permanent supportive housing, among other services.

“There are people who use drugs, who are homeless, who live in encampments, who might only need a little bit of support to go in a direction that will improve the quality of their life. But there are others who need a little more,” Hinson said.

Some people will need housing, wraparound services, continued treatment, and a sense of community in order to achieve their goals, Hinson said. He believes that even if there is more permanent and affordable housing built for people experiencing homelessness in Kensington, most — if not all — wouldn’t be able to afford to live in studio apartments for $700 or more per month, which is what the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) classifies as a fair market rent in the 19134 ZIP code.

“Affordability doesn’t mean the same thing for people with no income,” he added.

While city agencies are addressing the lack of long-term, supportive housing with programs like OHS’ Continuum of Care and Rapid Re-Housing, many agree that the City of Philadelphia cannot resolve issues of addiction and homelessness without additional support.

Both Hinson and Metraux believe that without increases to long-term housing with wraparound services, the City will continue to have to address issues surrounding encampments with unhoused people.

For example, Metraux stated that the state and federal governments will need to allocate resources to Philadelphia and support the work being done on the ground.

In July, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) gave the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) 863 housing vouchers, which is an unprecedented total of $10 million. The vouchers are meant to be given to people experiencing homelessness to pay their rent, and PHA expects the federal government to distribute more vouchers nationwide next year. Additionally, Philadelphia will receive $42 million to create housing for people experiencing homelessness from the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan.

While Hinson acknowledges these improvements, he believes that they are small steps for a city that has over 6,000 people in the emergency housing system, nearly 1,000 unsheltered people on the street at a time, and more than 40,000 people on a waiting list for government housing.

Community members anticipating new initiatives to address these issues in Kensington, like Klosterman, can’t help but recall the City’s previous efforts that didn’t produce long-term change. Klosterman said that while the City did provide funding for service providers and community organizations to better address the needs of people experiencing homelessness — the encampments and public drug use are as present as ever in the neighborhood.

“If you can’t find housing, can’t find employment, you’re going to wind up back where you started,” Klosterman said of the cycle of encampments. “People [with a substance use disorder] can’t function, and these resolutions are short-term Band-Aids.”

Meanwhile, he hopes that the new funding coming to the city will directly benefit those who need it most.

“Every year, they say they spend millions in Kensington on temporary housing, but there’s still hundreds of people on the street at a time,” Klosterman said. “They’re spending thousands on housing per person, and there’s still people without housing.”

Kensington Voice is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on economic mobility. Read more at brokeinphilly.org or follow on Twitter at @BrokeInPhilly.

Free accountability journalism, community news, & local resources delivered weekly to your inbox.