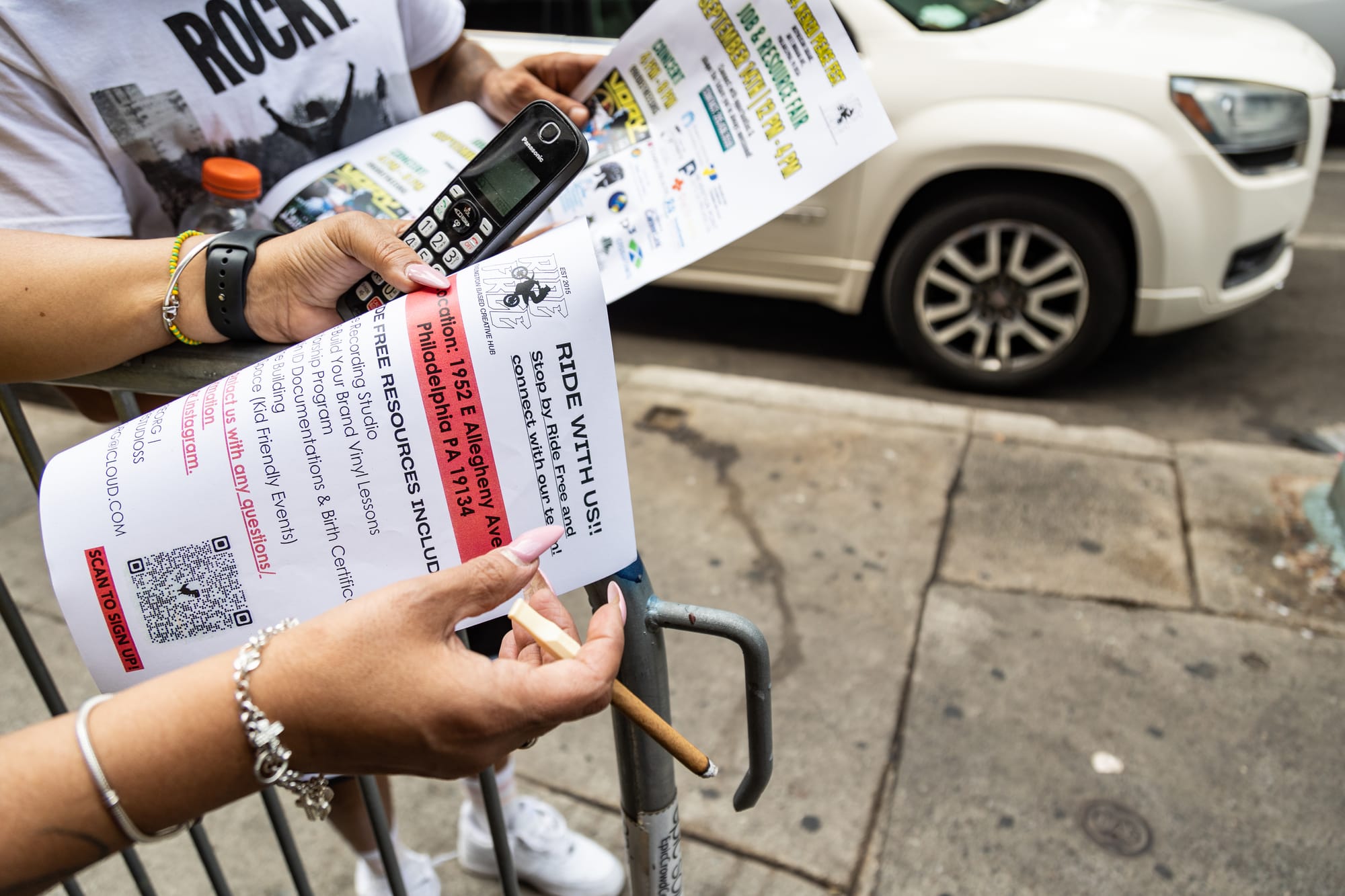

Thomas Bradley approached the corner of Jasper Street and Allegheny Avenue around noon on a late summer day. He stepped up to a cluster of young men gathered outside the mini-market there, ready to distribute a stack of flyers for nearby nonprofit Ride Free.

About a year ago, after serving five years in federal prison for a felony gun charge, Ride Free hired Bradley as an outreach worker. The organization offers job connections and other services to formerly incarcerated people, as well as those currently engaged in crime.

Bradley, 31, says he found out about Ride Free from a cousin as he was leaving prison. He went there to get a birth certificate and a fork-lift certification, and stayed.

“I was so hyped to do what they do,” he said. “I was like ‘these guys look like me, and they’re not in the street, and they’re getting paid.’ And I was like ‘I think I can do that’.”

Now Bradley makes $25 an hour trying to help people selling drugs in the neighborhood to choose another path. The work can be stressful, he said, but he likes the stability.

“I’d rather have this anxiety any day than me being on a corner, getting harassed by cops in 100 degree weather,” he said.

The day Kensington Voice shadowed Bradley on outreach, he and the men he was speaking with watched two Philadelphia Police Department officers confront another young man across the street.

The police department recently assigned 75 new academy graduates to the area, and arrests for both drug possession and drug sales are up, according to data from the District Attorney’s Office data lab.

Ride Free founder Lou Cruz said the work Bradley is doing is more important than ever given the recent uptick in arrests.

“Ride Free is out here every day talking to these guys and letting them know, ‘Hey, they're coming, they're coming to clean this up. What do you guys want to do?’”

Cruz says engaging with people who deal drugs is key to breaking up Kensington’s open-air drug market, but feels city leaders have overlooked this population while creating new law enforcement strategies for the neighborhood.

“I don't think anyone else in Kensington besides Ride Free has the amount of street guys coming in and out,” Cruz said. “Something’s going on in the neighborhood and they’re playing a part in it. We can also play a part in offering these guys opportunities and not just taking them to jail.”

‘I’m an ex corner guy’

Cruz, a Kensington native, was exposed to the drug market as a teenager, he said.

“I wasn't a shoot-em-up ... bang-bang guy, I wasn't here like, ‘Hey I want to kill you.’ … It was more, ‘I have a gun because I'm in the streets, and I know I need to protect myself,’” he said.

Even after getting arrested on gun charges, Cruz kept taking the risk. His parents tried to help by connecting him to jobs, but he didn’t want to work for somebody else.

“I kept finding myself back in the streets,” he said. “Every time my dad would give me a good job – back in the streets, get arrested again, come back out.”

About a decade ago, when Cruz was 28, his younger brother, who was also involved in street life, died by suicide.

That shook him, and he pivoted toward finding ways to get his friends out of the lifestyle. He bought a food truck using money he made selling drugs.

“I was like, ‘I'll buy this, but I'm not gonna work it, because I'm the big guy, right?” Cruz said. “So I have my friend that's selling drugs that I don't want to see selling drugs work this for me, while I sell drugs.”

Financial stability is a main driver for people who sell drugs, Cruz said. Poverty, lack of social opportunity, exposure to the drug market, lack of education, and household stress are all driving factors that can lead someone toward the drug trade, according to researchers from the University of Houston.

Cruz said he didn’t stop standing on corners until he was 33.

“I was in the drug market, I have cases. I did my probation,” he said.

In 2019, Impact Services director Casey O’Donnell recognized Cruz’s entrepreneurial spirit and offered him a free space to formalize the neighborhood work he was already doing.

O’Donnell continues to fund Cruz’s work, mostly using awards from the city’s anti-violence Community Expansion Grant program and the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency.

“I don’t know anyone in Philadelphia who can do what Lou does as well as he does it,” O’Donnell said.

All of the people employed at Ride Free have been involved with the criminal justice system in some way, Cruz said. He says that lived experience is an asset to building trust with people involved in Kensington street crime.

“I’m an ex corner guy,” he said. “These guys know us … they see that, and ‘if Lou can do it, why wouldn’t I sign up for that?’”

‘Transitioning is a huge headache’

Even when someone wants to disengage from criminal activity and get on a better path, it’s not an overnight fix, Cruz said.

There’s a lot of conflict between people who sell on Kensington streets, he said. There’s history, and everyone is connected.

“We live here, and sometimes we make decisions [based] on our environment,” he said. “I don’t like when people judge my guys. I don’t look at the black and white, I look at the person themselves.”

Many employees and participants at Ride Free are still on probation or fighting court cases.

“Transitioning is a huge headache around here,” he said. “They might swing at each other. They might get into an argument. One of these guys might come up with a pistol.”

But people keep their beef out of Ride Free’s basement location on Allegheny Avenue, he said.

“Sometimes they know each other from a friend shootin’ another friend or an argument that broke out at a bar,” Cruz said. “These are all street guys that might flip on us in a minute, but they’re doing good … it’s OK here.”

Usually when an employee or participant is getting entangled in something, Cruz sits them down for “a simple conversation” about how they have to conduct themselves to remain part of the organization.

“It’s that structure,” he said. “We're being us, but that means stopping all the street crap and applying it to being an adult.”

Career paths

On a summer morning at Ride Free, Sam San Jurjo was waiting for one of the young recording artists who’d been recording music in the organization’s free music studio.

San Jurgo started working there as a sound engineer about a year ago. He was let go this fall due to a grant that ran out.

In his early 20’s he had faced “a few major adult cases,” and then fought to stay out of the system.

“Thankfully and gratefully I was able to get my record expunged,” he said. “I had to make no police contact for two years, drug program, I was a struggling addict at the time.”

He found out about Ride Free from friends in the neighborhood. He started working there while raising his two young daughters.

“Complete 360. I been sober for the longest, I love what I do,” he said. “These were my intentions prior to being here, but I think Ride Free is a real visual representation of what Kensington could be. It’s beautiful, what we do here.”

Employment can “provide stability for people reentering society after incarceration, helping prevent criminal activity and recidivism,” according to a 2019 review of youth and adult reentry programs prepared for the U.S. Department of Labor.

Researchers consider programs that combine employment and help with cognitive behavioral therapy and case management to be the most promising.

The Rapid Employment and Development Initiative, or READI program, in Chicago was designed to address both gun violence and drug crime by providing therapy, group support and on-the-job support.

Men who participated in the READI program had 64% fewer shooting and homicide arrests 20 months after joining, according to a 2021 report from the University of Chicago.

Philadelphia launched a pilot version of READI in spring 2023. The city is contracting with three partner organizations, including Impact Services, and serving roughly 100 people.

Cruz says career connections are key, but the jobs have to pay more than a minimum wage to incentivize people away from drug crime.

“As a man, you have pride. You're not going to just leave a corner that you're making $4,000 or $5,000 a week on to go work in IKEA or ShopRite, in the same neighborhood you're from,” he said. “So it's career paths for us here.”

Forklift operation or long-haul trucking fit that bill, he said.

Cruz says people with a history in the drug market also have a ton of potential for entrepreneurial work.

“This guy on the corner that did 300 bundles a day … the responsibility that it takes to have a corner that sells 300 bundles of whatever drugs are some of the day, that's a business,” he said.

A neighborhood resource

Ride Free is housed underneath Impact Services, in the same building as the Philadelphia Police Department’s Kensington mini-station.

Impact also serves as the organization’s fiscal sponsor. The gleaming hardwood floors get daily attention from employees there. Much of the space has been painted by local artists. Two tables hold stacks of printed-out job postings from Craigslist and other websites – landscaping, construction, desk work, deliveries.

A large side room holds two rows of black-and-gold barbering chairs, which will soon be open for business. Sometimes weights and yoga mats are laid out in the main space for a makeshift community gym.

Young people come in an out of the space – like 21-year-old Gilberto Martinez, who recorded his song “Step it Up” at Ride free. The Kensington resident will perform the song at a September 14 concert in McPherson Square Park featuring hip hop artists from around the country.

“Step it Up” issues a call-to-action to his Kensington neighborhood – stay focused on the goal, even when the going is tough.

“It's about important messages for people in life, and some things that they should do in life, to see if it's best for them,” Martinez said.

The recording studio is there for adults, too. It’s a selling point during street outreach.

While out on an outreach walk, Thomas Bradley gave a hearty hug to a man who was standing near Kensington and Clearfield – the two met in prison.

The friend, rap artist Topfloor Tukie, said Bradley told him about Ride Free after he was released, and he started going by for free studio time.

“They do a lot of things that people charge for for free,” he said. “Like studio time. You can work on your craft in there if you have a passion for making clothes or anything.”

He says Ride Free addresses a lack of mentorship and creative outlets for young people in Kensington.

“They might not have the support that they need, they don’t have a way to jump start something,” he said. “If the younger generation were to know about it, it would give them more motivation to do what they feel they need to do or want to do in life.”

The organization is hoping to expand. Cruz says with more funding he would expand Ride Free’s space, engage more with prison staff and probation officers, and hire more outreach workers to spread the word about the services available.

Cruz says police officers should be connecting people to these resources.

“Start setting the officers up with knowing who these nonprofits are,” he said. “Instead of arresting the kid for selling drugs, bring them to Ride Free. Give them a flyer to Ride Free.”

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.