Kensington news: Breakfast with Santa, ‘Deck the Walls’ art show and more

Hey there, neighbors. Coming up this week, Santa is picture-ready for free photos at Scanlon Rec Center, local artists are

The trust ruled in favor of funding for Kensington schools, parks, and housing, but against home repairs and small business support.

The state trust overseeing Pennsylvania’s opioid settlement funds reversed part of its June decision that found Philadelphia’s Kensington spending non-compliant after city leaders presented their appeal on Thursday afternoon.

The trust ruled funding for Kensington schools, parks, and rent and mortgage relief compliant with national guidelines. After a 15-minute private deliberation, the board maintained that funding for home repairs and small business support was non-compliant.

The city can still challenge these decisions in Commonwealth Court.

The reversal followed an appeal by city attorney Ryan Smith, Keli McLoyd, director of Philadelphia’s Opioid Response Unit, Gina South, faculty director for the Penn Medicine Center for Health Justice, and James Washington, climate manager at Conwell Middle School. They testified to the conditions in Kensington and the opioid crisis’s impact on families and children.

They argued that improving the “social determinants of health,” which include factors like economic and housing stability and access to safe green spaces and learning environments, reduces the risk of substance use disorder and overdose.

The disputed funding involves $7.5 million the city earmarked for Kensington’s parks, schools, home repairs, rent and mortgage relief, and small business support — part of the city’s $20 million in opioid settlement money from a 2021 lawsuit against drug manufacturers and distributors. The city is supposed to receive $200 million over the next 18 years, in $20 million increments.

After the board’s reversal, Sincere Harris, chief deputy mayor under Mayor Cherelle Parker said the city would continue to use the funds for programs that “provide direct aid and resources for residents in Kensington.”

“The Parker administration strongly believes that the use of opioid settlement funds to invest in communities hit hardest by the opioid crisis is consistent with the guidelines provided for the use of these funds,” Harris said.

Despite the board’s vote, home repairs will continue in Kensington.

“Philadelphians who have already received repairs using settlement funds will not be expected to pay anything back, and residents on the waiting list for repairs can still expect to receive them,” said Amaury Avalos, spokesperson for the city’s Office of Public Safety (OPS), in an email.

Philly contended that improving Kensington’s built environment aligns with Exhibit E of the trust’s order, which lists efforts “to discourage or prevent misuse of opioids through evidence-based or evidence-informed programs or strategies.”

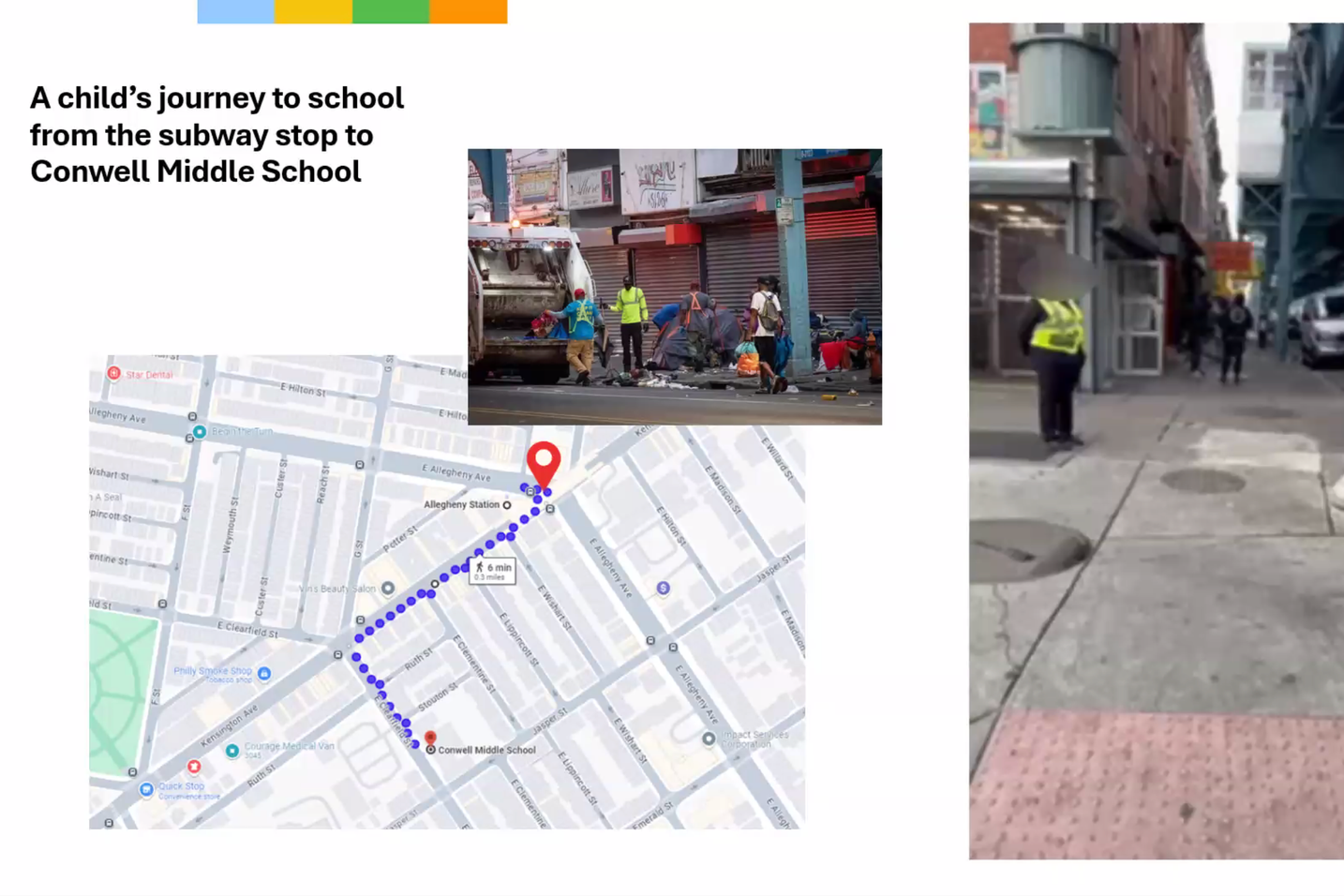

The city presented scientific studies, evidence-based arguments, and a video showing a Conwell Middle School student’s walk to school along Kensington Avenue.

“The oversupply and proliferation of opioids hit harder here than in any single neighborhood in the United States,” McLoyd said, emphasizing the need for prevention efforts in Kensington.

“To dispute this fact is to deny the reality of the effects of the narcotics trade in the neighborhood, to deny the constant and inescapable trauma experienced by every Kensington resident, and to deny the incredibly well documented relationship between trauma and risk of developing opioid use disorder,” McLoyd said.

McLoyd added that traumatic childhood events, or adverse childhood experiences, like witnessing a violent crime or overdose, having a parent with an addiction, and experiencing housing instability, are linked with future substance misuse.

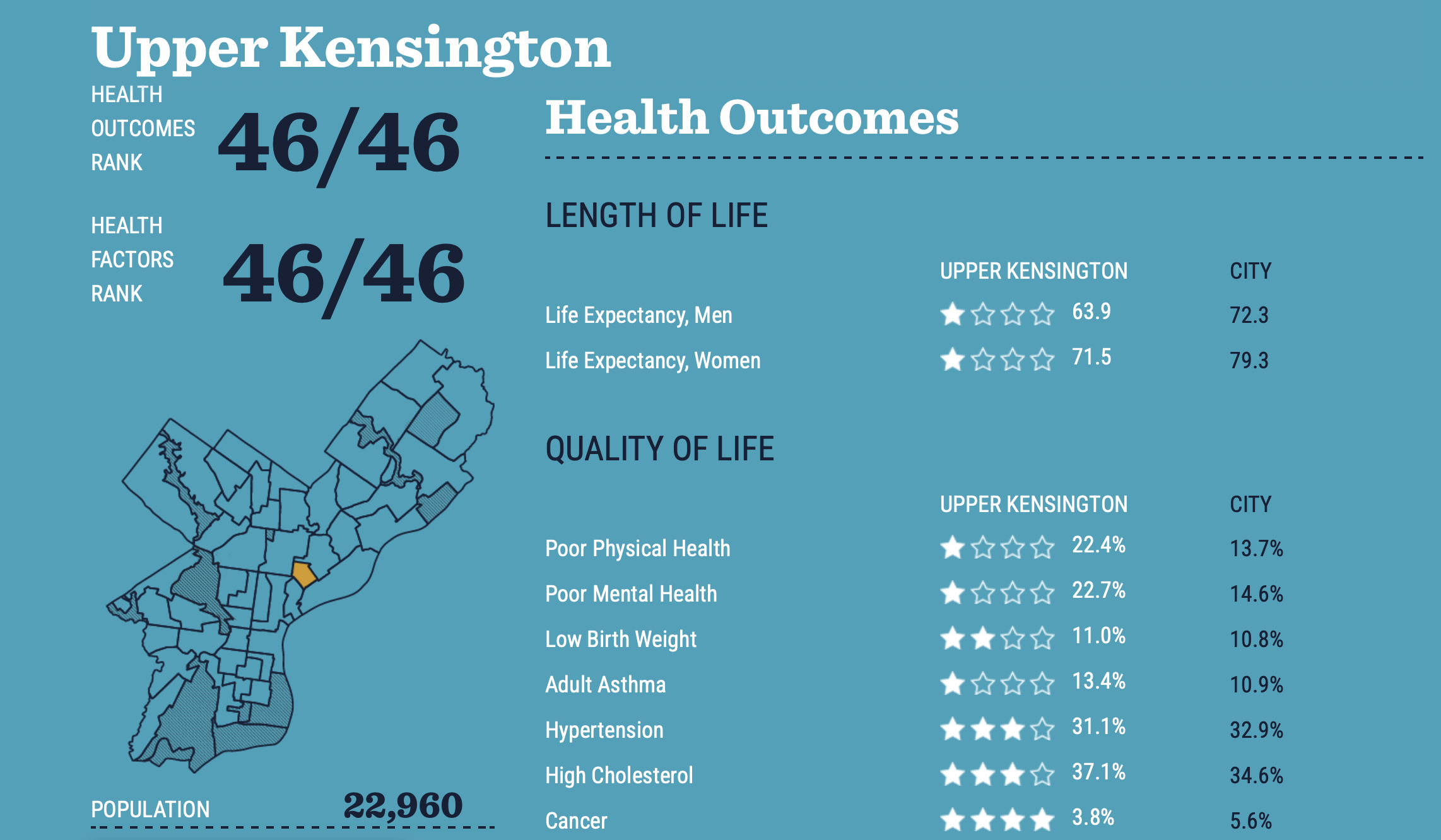

In Kensington, up to 45% of residents reported four or more adverse childhood experiences (ACES), compared to 16% of Americans nationwide, McLoyd said. For over 25 years, researchers have linked ACES to the leading causes of death in the United States.

“All of this means, in essence, that this entire community as a whole is at a higher risk of developing opioid use disorder and experiencing an overdose because of the conditions in the Kensington neighborhood,” McLoyd said.

That is why the city invested in “community-based” prevention methods — interventions for the entire neighborhood — she said.

McLoyd also argued that home repairs help stabilize residents, while small business support reduces the vacant buildings and increases economic opportunities,both of which lower the risk of opioid use disorder.

South, an ER doctor and expert in opioid use disorder prevention, said she has spent the last 14 years studying how home and neighborhood conditions impact health outcomes. She testified that housing and community environments can increase or decrease blood flow to the brain, stress levels, and heart rate, all of which influence someone’s risk of developing an opioid use disorder.

South said many social determinants of health include things people can see, like housing and sidewalk quality, parks, and trash.

Other social determinants, she said, “are unseen but deeply felt.”

“[Like] knowing there was a shooting on the block over from your house, feeling hungry all the time ... knowing that your neighbor down the street has a leak in their roof and its causing mold to form, and has a 10 year old son with asthma who's in and out of the hospital because of it,” she said.

State Sen. Christine Tartaglione, who represents Kensington and voted that the city’s Kensington spending was non-compliant over the summer, reversed her vote Thursday to support the city’s Kensington spending in all categories.

Since the trust’s June decision, residents have argued the money for home repairs, parks, and schools, is vital in helping to repair the community living within the opioid epidemic.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.

Free accountability journalism, community news, & local resources delivered weekly to your inbox.