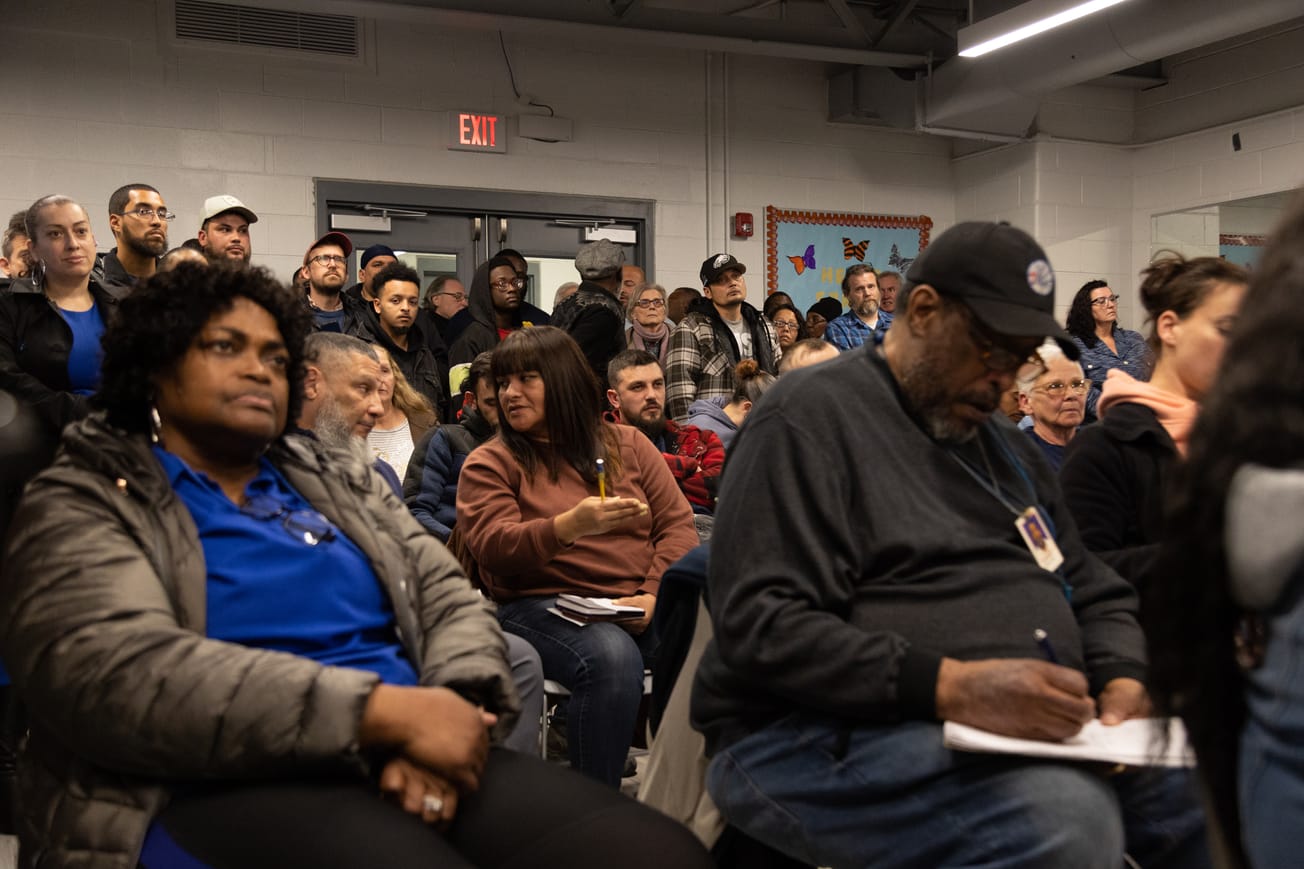

Mayor Cherelle Parker defended the proposed 76ers arena at a Kensington town hall last week, where she faced concerns over displacement, the project’s proximity to Chinatown, and the developer’s controversial history of gentrification, which critics say feeds into the history of racism against Chinatown.

The $1.3 billion proposal, which would move the team from South Philadelphia’s Stadium District to Center City, is scheduled for a third City Council committee vote on Wednesday afternoon.

At the Dec. 4 town hall, Parker described the plan as an economic catalyst, emphasizing its potential to generate jobs and revenue for the city.

“My decision is about everything that’s beyond the basketball. The $1.3 billion investment,” she said. “I’m thinking how much we can leverage what’s outside the arena.”

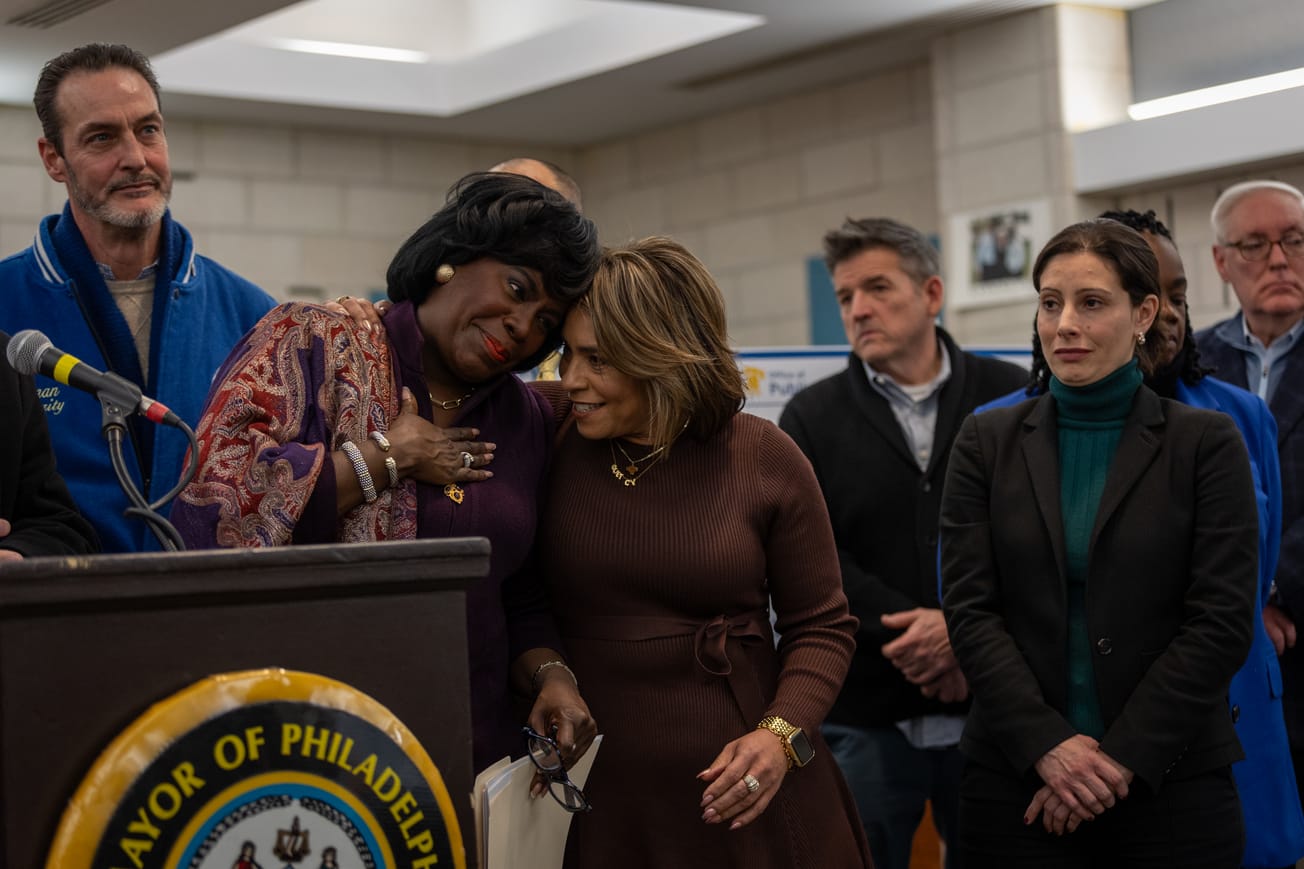

Councilmember Quetcy Lozada of the 7th district joined Parker at the meeting, while Councilmember Mark Squilla, who proposed the arena legislation and whose district includes Chinatown and a portion of Kensington, did not attend.

It was Parker’s first Kensington town hall since May, when she promised to eliminate the neighborhood’s open-air drug market, but cautioned that her enforcement strategy would be like “building the plane while I’m flying it.” Kensington residents have been calling for more engagement from the city, as their quality of life concerns persist.

The arena town halls were an attempt for transparency, Parker said.

Parker’s administration emphasized the plan’s potential to revitalize the Market Street corridor, which several mayors have attempted before.

Sophie Bryant, a member of Parker’s policy team, hailed the plan as a way to return the area around Market East to “its glory days.”

Parker’s staff acknowledged Chinatown leaders’ resistance over the years to building an arena in their backyard, yet promised to do what they could to protect the community while construction is underway.

John Mondlack, the city’s deputy director of development services, admitted there were no guarantees that Chinatown would thrive.

“Can we guarantee that Chinatown thrives? No, of course, we can't,” Mondlack said. “What we can guarantee is that we're going to do everything in our power to utilize all the resources that we have access to … to try to mitigate whatever it is.”

Opposition over displacement, gentrification

At the Dec. 4 meeting, Parker referenced opposition to the arena plan.

“You hear it all the time: big business, billionaires, and corporations,” she said. “Some people can make an argument about not wanting entrepreneurs, business people to do business in the city of Philadelphia. I'm the mayor. I need this pie to grow. I want more businesses doing business in the city of Philadelphia.”

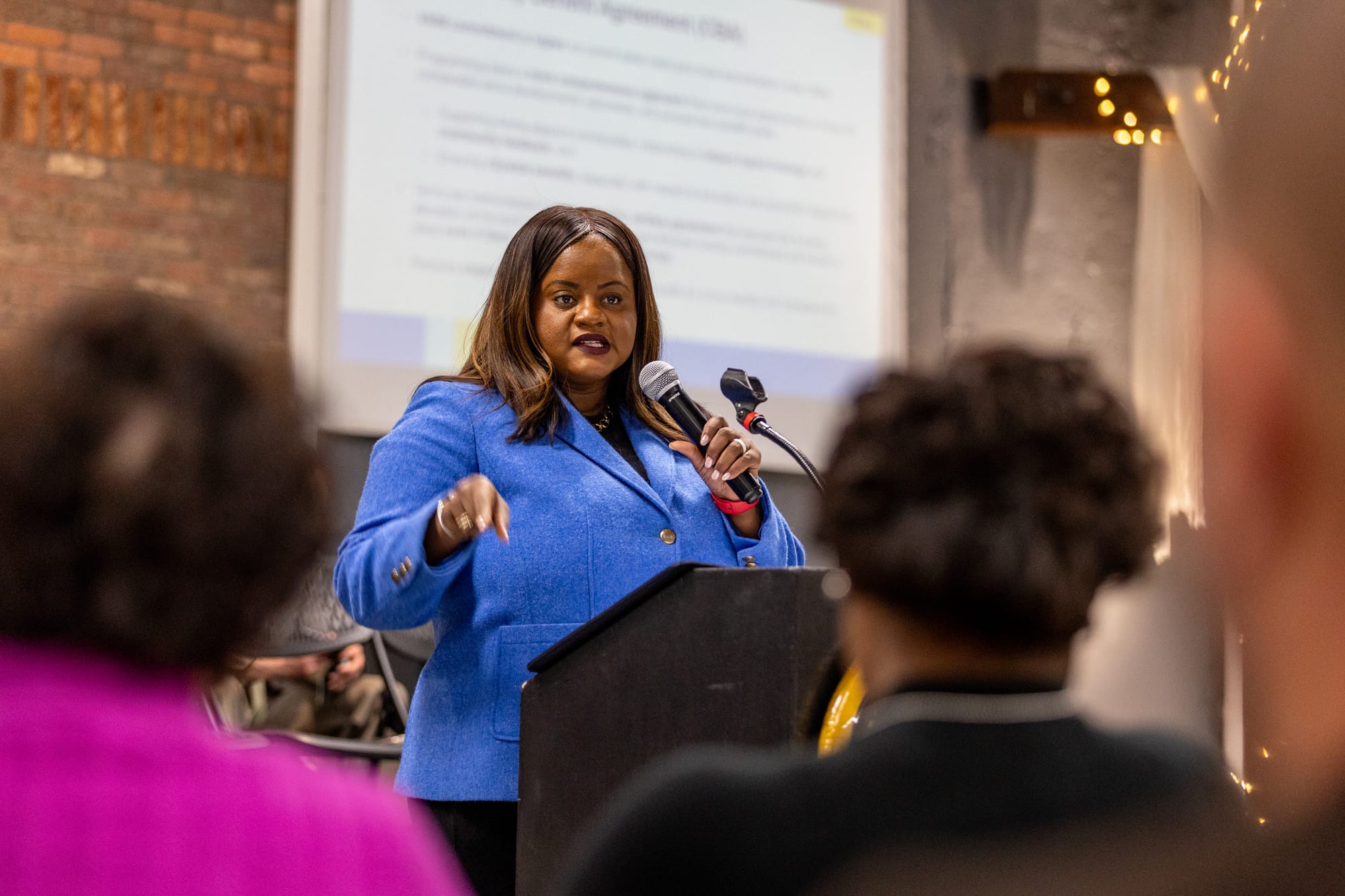

For months, Parker’s administration has touted the proposed arena as a way to bolster education and employment in the city. Political opponents like At-Large Councilmember Kendra Brooks have called the deal a “$400 million tax break” over the next 30 years.

Tiffany Thurman, Parker’s chief of staff, said the deal would “preserve Chinatown” and break barriers for communities of color across the city.

“The 76ers can jump-start redevelopment,” said Jessie Lawrence, the city’s director of planning and development, during the meeting.

But critics raised concerns about the arena’s impact on Chinatown, which sits just feet from the proposed site. Vivian Chang, executive director of Asian Americans United and a leader with the Save Chinatown Coalition, said the project would accelerate gentrification.

“They just openly admitted it,” Chang said in a phone call with Kensington Voice, responding to Lawrence’s statement.

Chang’s concerns echoed four city impact reports, which warned the project could stress vulnerable businesses, particularly in Chinatown’s financial, healthcare, grocery, and wholesale sectors. Half of Chinatown’s businesses could face negative impacts, the study found.

Aylene, a Kensington resident, pointed to parallels with her community’s experience of gentrification.

“When we see these price increases it's going to destabilize something the way that I've seen it in my community,” Aylene said. “To see what's happened to Kensington, I don't want to see that get pushed out around the city.”

Parker acknowledged fears of displacement and cited “predatory agreements of sale” she witnessed growing up.

Mondlack highlighted a $1.6 million disruption fund for Chinatown and additional measures like affordable housing initiatives, grants, and parking improvements to offset the arena’s impact.

Opponents, however, criticized the disruption fund as insufficient.

“I feel very unwell about this process,” said Jayson Massey, a Nicetown resident who attended the meeting. “This doesn't … seem like a good deal at all.”

City council has proposed doubling the community benefits agreement, which is meant to lessen the impact on the Chinatown community, from $50 million to $100 million. The No Arena in Chinatown Coalition calls it “pitiful,” demands nothing less than $300 million, and is pushing to delay the vote until 2025.

Seth Anderson-Oberman, executive director of Reclaim Philadelphia, did not attend the Kensington town hall but attended the town in West Philadelphia the night before.

He called the disruption fund “nothing.”

“It’s peanuts,” he said.

Some attendees urged Parker to negotiate a better deal or consider alternative locations, like Northeast Philadelphia. In response, she defended the site selection, citing recommendations from “subject matter experts,” a phrase she repeated through her team’s 90-minute presentation before opening it up to public comment.

Parker also drew comparisons to her childhood neighborhood of Mount Airy, which experienced divestment and rapid change in the 1980s.

“I am wholeheartedly committed to ensuring that what happened in my neighborhood does not happen in Chinatown or nowhere else in the city of Philadelphia,” she said.

Chang countered, urging Parker to extend the same protections to Chinatown.

“Therefore shouldn't you fight even harder to protect every other community?” Chang said.

Frustration over lack of engagement

Community members also criticized Parker’s administration for inadequate engagement with Chinatown leaders.

During public comment, one attendee pointed to the city’s history of racial exclusion that led to the development of Chinatown.

“What I've learned from a lot of Chinatown elders is that that arena fits into this long painful, violent, racist, history,” they said. “And what I understand is that that coalition of folks in Chinatown has tried to meet with you six different times and you haven't met with them.”

Parker denied this claim twice, calling it “untrue” and “not factual.”

Thurman said she and other staff members have held meetings with “every leader of every stakeholder group” and meeting minutes exist to prove this, though the administration declined to release them to the public.

Chang clarified that meetings involved the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation and the previous administration, rather than Parker’s team.

“We met with them beginning with [Mayor Jim] Kenney’s Administration,” Change said. “So, it really does not represent her at all.”

Both Anderson-Oberman and Chang said when Parker did meet with their coalition in September, the meeting was last-minute and she had no intention of listening to their concerns.

“[Parker] brought us all in and then immediately said, ‘I'm announcing support for the arena’,” Chang said. “We were like, ‘Wait this is not a meeting then why are we here?’”

“This is really the tip of the spear”

For opponents like Anderson-Oberman and Chang, the arena represents more than a development project – it symbolizes broader concerns about the city’s future.

“This is really about the future of Philadelphia and whether or not Philadelphia is going to continue to be a livable, sustainable city for working-class people,”Anderson-Oberman said.

They argue that approving the plan in its current form sets a dangerous precedent.

“This is really the tip of the spear,” Chang said.

Anderson-Oberman agreed.

“If this seal goes through in its current form, it will just be a green light to developers moving forward that they don't have to seek the approval of the community, or the neighborhood that they want to develop in,” he said. “They can just do whatever the hell they want.”

As the No Arena in Chinatown Coalition prepares for the next City Council meeting, Chang stressed the importance of continued opposition.

“This is not a done deal,” she said. “That's so important. Because from the very beginning, the developers have tried to convince everyone it’s not worth fighting. That’s why we’re always trying to fight.”

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.