Mayor Cherelle Parker’s administration has ended a major city-funded grant program that allowed Kensington residents to decide how national opioid settlement dollars were distributed in their neighborhood.

The Overdose Prevention and Community Healing Fund, or Prevention Fund, used a community-led grantmaking process to distribute $3.1 million to 43 organizations in 2024. It will no longer be managed by the Scattergood Foundation, which oversaw the participatory funding process, according to a spokesperson for the foundation.

Meanwhile, the Parker administration has launched a new $3.6 million grant program for community-based organizations dedicated to communities impacted by the opioid crisis, led by the Office of Public Safety.

However, the city has not yet opened an application process for the program, leaving it unclear how–or if–organizations can apply and what role, if any, community members will play in selecting grantees or overseeing funding.

Last year, the Prevention Fund’s application deadline was in January. Some current grantees said they have not received any information about an opportunity to reapply.

“To guarantee funding is allocated where it is most impactful, the Office of Public Safety will continue to foster relationships with vetted community organizations making a tangible difference combating the overdose crisis throughout the city,” wrote Chief Public Safety Director Adam Geer in a March 7 press release.

The city declined to comment on whether the new grant program is a replacement for the Prevention Fund and would not provide any further details about the grant process.

It is also unclear whether the city will continue to contribute opioid settlement dollars to the Kensington Community Resilience Fund, or KCR Fund, another community-led grantmaking fund managed by Scattergood for organizations working to improve the quality of life in the neighborhood. The city issued an open call for KCR Fund applications in December.

“We don’t have a final answer from the city,” said Caitlin O’Brien, director of learning and community impact at Scattergood, adding that the foundation is still hopeful the city will support that fund.

Now in its fifth year, the KCR Fund has distributed over $1.1 million to more than 50 organizations. Scattergood has managed the fund since 2022, following its oversight by the Bread & Roses Community Fund, which also uses a community-led approach to grantmaking.

Scattergood has since paused the latest KCR Fund grant cycle, leaving 53 applicants waiting. During the last two grant cycles, the city contributed $250,000 of opioid settlement money to the fund and Scattergood was expecting the same amount this year, O’Brien said.

An email from Scattergood to grant applicants stated that “should the Parker administration elect not to participate, the KCR Fund will move forward with the support already committed by the Scattergood Foundation and other private philanthropic partners, including the William Penn Foundation, Patricia Kind Family Foundation, and the Nelson Foundation.”

Scattergood had been meeting with city officials to move the next Prevention Fund grant cycle forward, O’Brien said. The city then asked the foundation to pause its work and eventually notified them it would no longer support the program.

By that time, Scattergood had already received 90 applications for the Prevention Fund’s community granting group, which would have selected the grantees, according to O’Brien.

Scattergood President Joe Pyle said the foundation hopes the administration will maintain a participatory funding model for the Prevention Fund.

“Opioid settlement monies represent justice for the individuals, families, and communities that have been ravaged by the opioid epidemic, including those who have been most impacted by the epidemic in direct decision making about how dollars are spent is critical to restoring agency in these communities,” Pyle wrote in an emailed statement. “These participatory funds were the only dollars that the City had designated toward community organizations with community voice at the center and had been lauded as a national model for how to distribute settlement funds.”

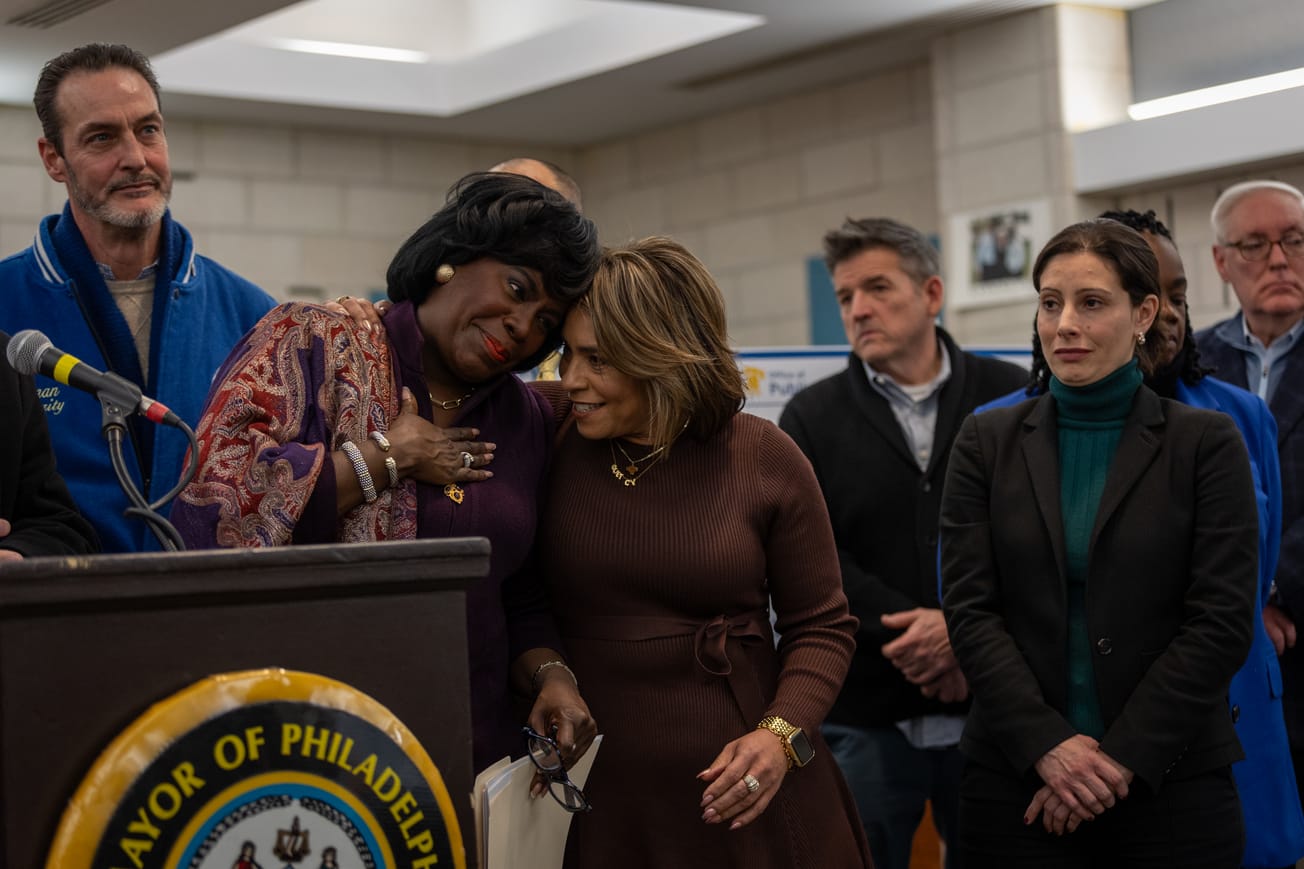

Councilmember Quetcy Lozada, who represents the 7th District, where much of the opioid settlement funding has previously been distributed, said the Parker administration has spoken with her about “changing the process for the use of opioid settlement funds.”

“But I've also received the commitment from them to ensure that some of the community groups that do the grassroots work, continue to be funded,” Lozada said. “And so I'm looking forward to having that conversation and figuring out who are those groups, what is their work, and how do we continue to do that work.”

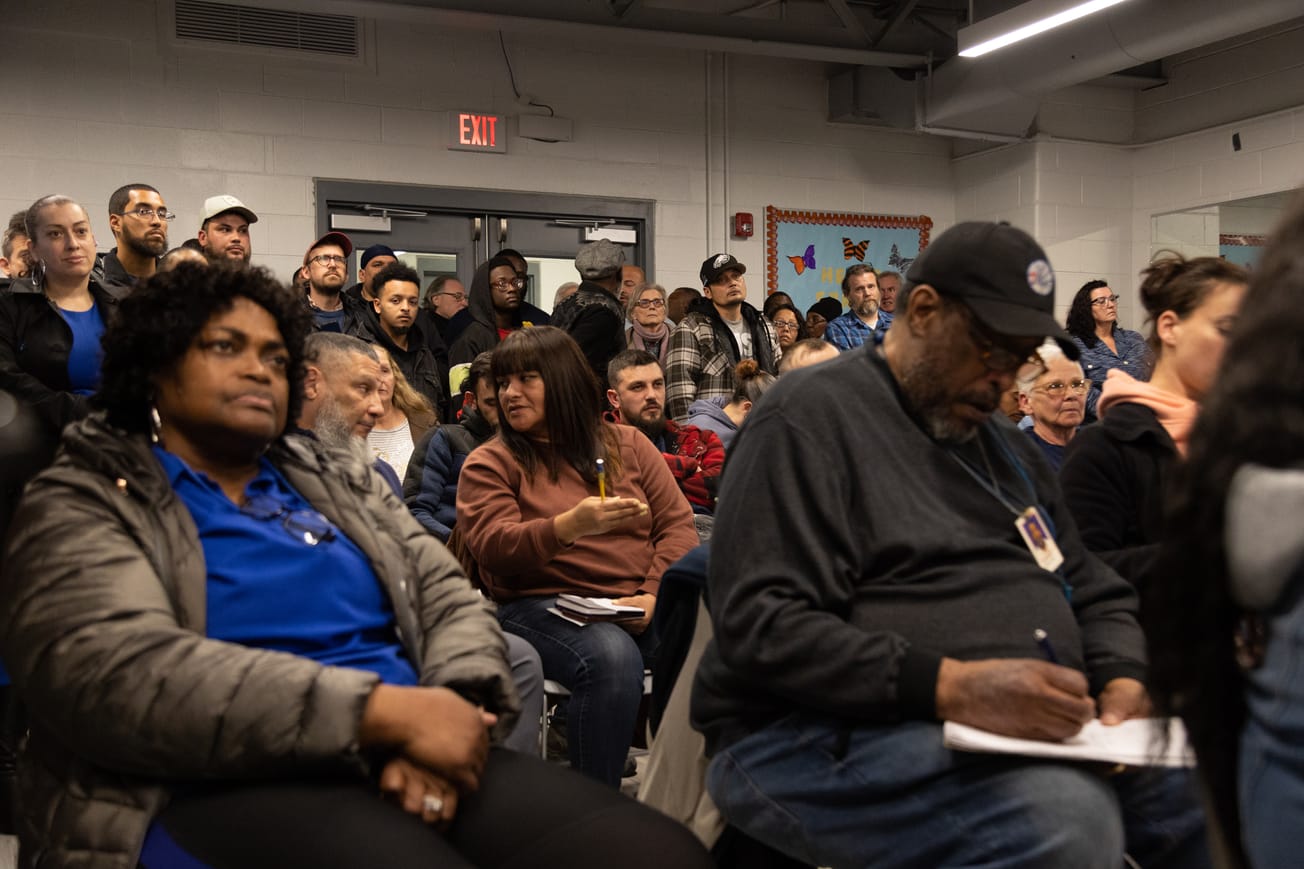

Funding decisions should be rooted in community wisdom, residents say

Kensington residents who have been involved in Scattergood’s community-led grantmaking processes say it gave them a sense of pride and ownership.

“You can’t tell me what I want and what I need if you’re not in the trenches with me,” said Arlene Ortiz, a member of the KCR Fund community granting group.

“This Kensington world is way different. They don't see what we see when we walk out our front door. People in the mayor's office don't live here, so they don't know.”

Ortiz has lived in Kensington for 18 years with her 18-year-old daughter. She said being on the committee has helped her learn more about what organizations do in her neighborhood. Her daughter, who works for Klean Kensington, which is funded by the KCR Fund and Prevention Fund, inspired her to get involved.

“I want to make a change before my time is up here on this planet,” Ortiz said. “At least I can say, ‘I helped make that happen.”

Another resident and community granting group member, who asked to remain anonymous, said community members should be making the funding decisions because they “are living in it.”

“People make decisions in places, and then they get to go home,” they said. “We stay here.”

Through tears, they described the chance to direct funding as a rare opportunity.

“We don't see a lot of money out here. We don't come from a lot of money. So

to be able to help out with money is amazing,” they said. “When I got to be able to do this, I cried because I love Kensington so much.”

They said the process also brought together a diverse group of residents committed to staying in Kensington and working to improve it.

“We all just want to help Kensington, and none of us talk about leaving here,” they said. “We don’t want to leave here.”

Sarah Laurel, a Kensington resident and director of the harm reduction nonprofit Savage Sisters, served on the Prevention Fund’s 2024 community granting group.

While she didn’t agree with all of the group’s decisions, she said she respected the voting process and still wants residents to lead funding decisions.

“While it may not have been highly in favor of what I support, which is harm reduction, it was still the community that made that decision. I think it's important that we don't mute the voices of community members so that the government can have their hand in things and make deciding factors on funds that the community deserves,” Laurel said.

Laurel said she wished there had been more education for advisory members about substance use, harm reduction, and ethical and legal practices in treatment and prevention. According to O’Brien, Scattergood had been preparing to offer such a workshop for the 2025 Prevention Fund granting group.

Now, Laurel worries the money won’t be allocated toward harm reduction or evidence-based practices at all.

“I don't think that this administration is trending toward evidence-based practices. And having them take the reins on distributing this funding is muting and gagging the community and our needs in a very aggressive manner,” she said.

Experts in philanthropy who advocate for community-led grantmaking say the city’s move away from a participatory model signals a lack of trust in residents to decide how funds should be used in their own neighborhoods.

“People who are closest to the problems will have the best knowledge on where the solutions are and where funding should go,” said Huong Nguyen-Yap, vice president of equity and justice at Northern California Grantmakers, a membership association that educates foundations around their philanthropic practices.

In this case, she said, “it feels like they no longer value their lived experience or their decision making,” which could lead to harmful consequences.

“There’s a danger in making a decision that the community doesn’t need or isn’t rooted in the voice or knowledge of the community,” Nguyen-Yap said. “If you’re not spending your time in the community, without a process that involves the community, you’re going to miss the mark on where those funds are needed.”

Cynthia Gibson, a widely published thought leader who researches participatory approaches to philanthropy, said real change doesn’t come from a top-down approach. Through Gibson’s research, she has found that involving people with lived experience in decision-making leads to better outcomes for the programs they fund.

“At the core of these approaches is the growing realization that innovative ideas about resolving hard issues don’t spring forth solely from traditional experts and power brokers,” Gibson said.

Grantees voice concerns about programs at risk

Current and former grantees of the Prevention Fund and KCR Fund expressed disappointment that Scattergood would no longer manage the Prevention Fund. They also voiced concerns about losing the participatory grantmaking model and fears that the KCR Fund will shrink.

Rebecca Fabiano, executive director of Fab Youth Philly, a nonprofit that has received grants from both funds, said she is unsure whether her group’s summer program will be able to run this year. While funded by other sources, Fab Youth Philly’s summer program relies heavily on the Prevention Fund.

“Because we don't have any info about the overdose grant, our summer program is at risk for not running,” she said.

Fabiano described the grantmaking process with Scattergood as “extremely transparent, thoughtful, community-centric — things that grantmaking processes usually aren’t.”

“It was a welcome change as a grantee,” she said.

She also praised the foundation for providing technical support and organizing networking events among grantees, initiatives that may not continue under city management.

“I appreciate that Scattergood is very nimble and responsive... things that have been more challenging with the city because there’s more bureaucracy and less transparency,” she said.

Some also wondered whether the mayor’s office would begin hand-picking grant recipients and move away from supporting harm reduction organizations, or organizations that aren’t favored by the city, without a transparent decision making process.

Roz Pichardo, a resident who runs the Sunshine House, a community outreach center on Kensington Avenue, said she worries that harm reduction workers may no longer be able to provide adequate resources to people experiencing addiction and homelessness.

“People need to have a seat at the table and state why we believe we should still have access to these funds,” Pichardo said.

The Sunshine House has operated as a warming center during the winter and a year-round resource hub. Pichardo helps people access addiction treatment, provides clothing, food, and wound care, and reconnects people with their families.

“People are afraid to speak out... I got too much to lose. It’s too many people dying,” Pichardo said. “We can’t afford to be afraid. We have to be able to talk about this and say this needs to happen.”

If the mayor’s office is concerned about misuse of funds, Pichardo suggested creating stronger guidelines—not eliminating community-led decision making altogether.

“If the mayor had any questions about whether the people who received these funds are actually doing the work. Why hasn't she set foot in the Sunshine House?” she said. “I just hope that the decisions they make don't cost another life.”

Other grantees said the community-led process offered something unique: the chance to directly learn what residents want and need in their neighborhoods.

“[To] really hear from folks actually in our neighborhood what they want, and hear the proposals put forward, what is actually going to help our community,” said another 2024 grant recipient who asked to remain anonymous. “That process– it's a lot of work, but it's very thoughtful, and they've done that quite well.”

Jeremy Chen, director of Klean Kensington, received $20,000 through the Prevention Fund during the 2024 grant cycle. His organization pays about 50 Kensington teens $18 an hour to clean streets, transform blighted lots into community gardens, and maintain those spaces.

Losing that funding, he said, would take money out of teens’ pockets and limit community improvement efforts.

“It’s a loss not just for the teens but also for the neighborhood,” Chen said. “Assuming I can’t compensate through other grants, it’s about $16,000 less for teenagers. That’s about 900 hours of teen work. With that time we could create a whole new community garden.”

He said the Prevention Fund dollars should be used to help Kensington heal from the open-air drug market and its related challenges.

“This is like opioid reparations money,” Chen said.

**Editor’s Note: Kensington Voice received a KCR Fund grant in 2023 and 2024 but did not apply for the current grant cycle.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.