Last week, Michael Hurd woke up under the I-95 overpass at Girard Avenue surrounded by state officials, Philly police, city staff, trucks, and a bulldozer.

The cleanup was organized by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) “in conjunction with staff from the City of Philadelphia,” according to a PennDOT spokesperson.

The Philadelphia Police Department and Office of Homeless Services were also present, said Sgt. Eric Gripp, a spokesperson for PPD.

Hurd had been living there for about two years, tucked under the highway between roads, parking lots, and some shrubbery. He couldn’t specify who the officials worked for – “it was a little bit of everybody,” he said – but they ordered him to move and threw away his futon.

“They dropped a dumpster and threw [all of our belongings] away,” he said. “Told us to get gone. We lost everything. If it couldn't be put in a backpack or carried, it was thrown away.”

According to Hurd, he was one of about 10 people living in his encampment, including a man who had lived there for eight years. He said they didn’t have enough time to make plans for their belongings or find somewhere else to stay.

“I don’t know where else to go,” he said while collecting money a few blocks away.

Tom Eubig, who lives next to the PennDOT property, said there were multiple encampments located in the area that were no longer there after the cleanup last week.

“Somebody cleared people; I don’t know who. My wife said she saw people with trucks,” Eubig said.

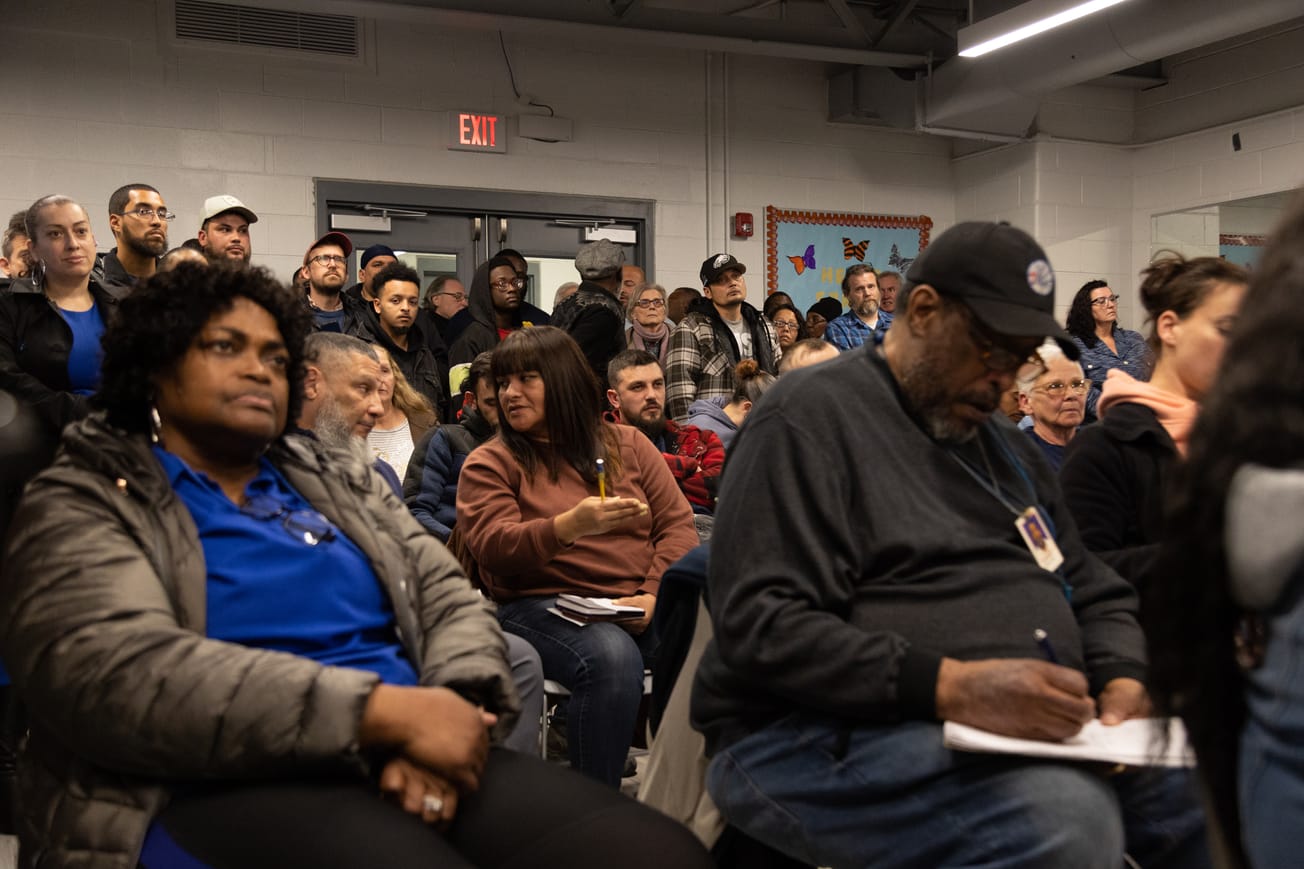

In an internal city email obtained by Kensington Voice, city officials estimated approximately 30 people were living below I-95 near Aramingo Avenue, Girard Avenue, and Richmond Street on the day PennDOT cleared them. The email indicated that the city was planning an “encampment resolution” for the area on October 1 and that the city intended to post an encampment resolution notice on August 29.

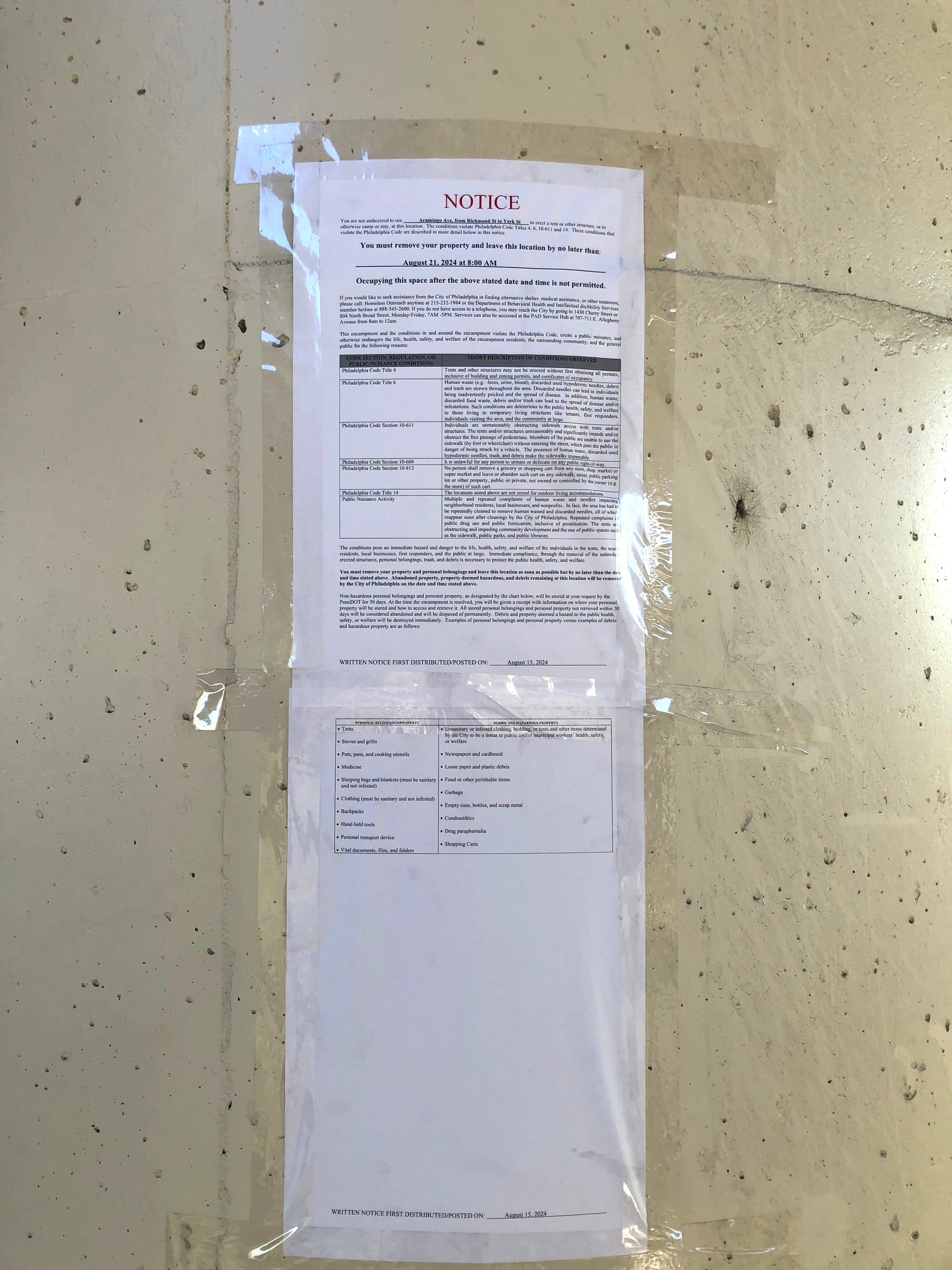

The day after the sweep, two city encampment resolution notices were hanging in the area ordering people to leave by August 21 at 8 a.m. with only six days of notice. There were also anti-loitering, camping, and dumping signs threatening up to 10 years in prison.

“PennDOT posted the signs,” said Gripp. “They were not Philadelphia’s signs; they were PennDOT’s.”

Gripp also said the city’s encampment resolution policy is “germane to City of Philadelphia public property” and that while PPD and OHS were present, they “did not participate in [PennDOT’s] cleanup efforts and did not relocate anyone.”

“Neither the PPD – nor the City of Philadelphia – consider this an encampment resolution,” Gripp wrote in an email to Kensington Voice. “...PennDOT does not require the City of Philadelphia’s permission to clean up their own properties.”

But according to PennDOT spokesperson Robyn Briggs, “the city’s Office of Homeless Services and police department assisted with the relocation of 8-10 people located on PennDOT property.”

“Bad practice” and “bad policy”

The National Homelessness Law Center (NHLC) claims the sweep is unconstitutional, partly because it violates the city’s encampment resolution policy. It also violates the Fourth Amendment, which protects people from unreasonable searches and property seizures by the government, according to NHLC.

The city’s “encampment resolution” policy outlines the city’s process for clearing encampments, which includes “the disposal or storage of personal items, tents, and other structures removed from public property as well as outreach and engagement of individuals to ensure connections to services.” It defines an encampment as individuals using tents or other structures to live outside and requires the city to provide advance notice before displacing the people there.

According to the policy, the city is supposed to give those who have lived in an encampment longer than 30 days at least 30 days of notice before a sweep. The policy also requires the city to “offer alternative locations for individuals or identify available housing for encampment occupants” and to offer storage for personal belongings for a minimum of 30 days.

Regardless of who led or participated in the encampment sweep, according to William Knight, a senior attorney for NHLC, the “lack of notice, lack of due process, and the destruction of property” was still a constitutional violation. It was also “bad practice,” and “bad policy,” Knight said.

“There is very likely a viable legal claim for all of their civil rights being violated because the state didn't comply with what the government told them it would do,” he said.

According to Knight, the city has established expectations through its encampment resolution policy, and is communicating what it believes to be reasonable ways to handle encampment sweeps, like giving at least 30 days of notice and identifying available housing.

“The people that don't have anywhere else to go are relying on those laws and notice provisions that the state either ignored or the city cooperated with the state in disregarding, and that is a violation, not just of their own municipal code, but it's a violation of peoples’ Fourth Amendment rights,” he said.

Instead, Knight suggested providing access to treatment and permanent supportive housing.

“It's less expensive to do that than it is to use our criminal punishment system,” he said. The cost of criminalizing homelessness “is buried, and the people are scattered and invisibilized, so it makes the problem worse,” he said. “It costs more money. It's inhumane, but it's politically expedient.”

PennDOT spokesperson Briggs said PennDOT does not comment on legal issues. She did not share what resources or services were offered to those living in the encampment. Sgt. Gripp said OHS services were “offered and declined.”

Hurd said no one offered to store his belongings, nor connect him to services or housing.

“They don’t care,” he said.

“We just want somewhere safe to sleep”

The I-95 underpass protected Hurd from the rain and the lights there made him feel safe, he said. Now, he’s concerned he’ll be arrested if he returns.

“We just want somewhere safe to sleep,” Hurd said. “Spreading us out has us worried about getting robbed every night.”

He said he doesn’t like to sleep in front of people’s homes, so he’s considering sleeping in an alleyway to be “left alone” and not “messed with by police.”

Knight said that people who are unhoused usually congregate because it is safer. Displacing people, he said, forces them to live in smaller communities and makes them “more ripe to be victims of crime themselves.

Hurd said police regularly offer the ultimatum of “jail or rehab.” But that choice, he said, forces people to choose rehab when they aren’t ready. Then, when they leave treatment, they think they can consume the same amount of drugs as before, which leads to overdose deaths, he said.

“We're all still human. Don't treat us all like we're in a fishbowl and the water's gonna run out and we should all die the same,” he said.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.