Content warning: This story contains descriptions of gun violence and its aftermath.

A new city program that hires a professional cleaning service to handle blood and other remains after outdoor shootings launched this month in the 25th police district.

Previously, police responding to a shooting on a street or sidewalk would collect evidence and then call in the Philadelphia Fire Department to hose away any residue, according to city personnel.

But residents and advocates say despite those protocols, family members and neighbors sometimes do the job themselves, at their own risk of physical and psychological harm.

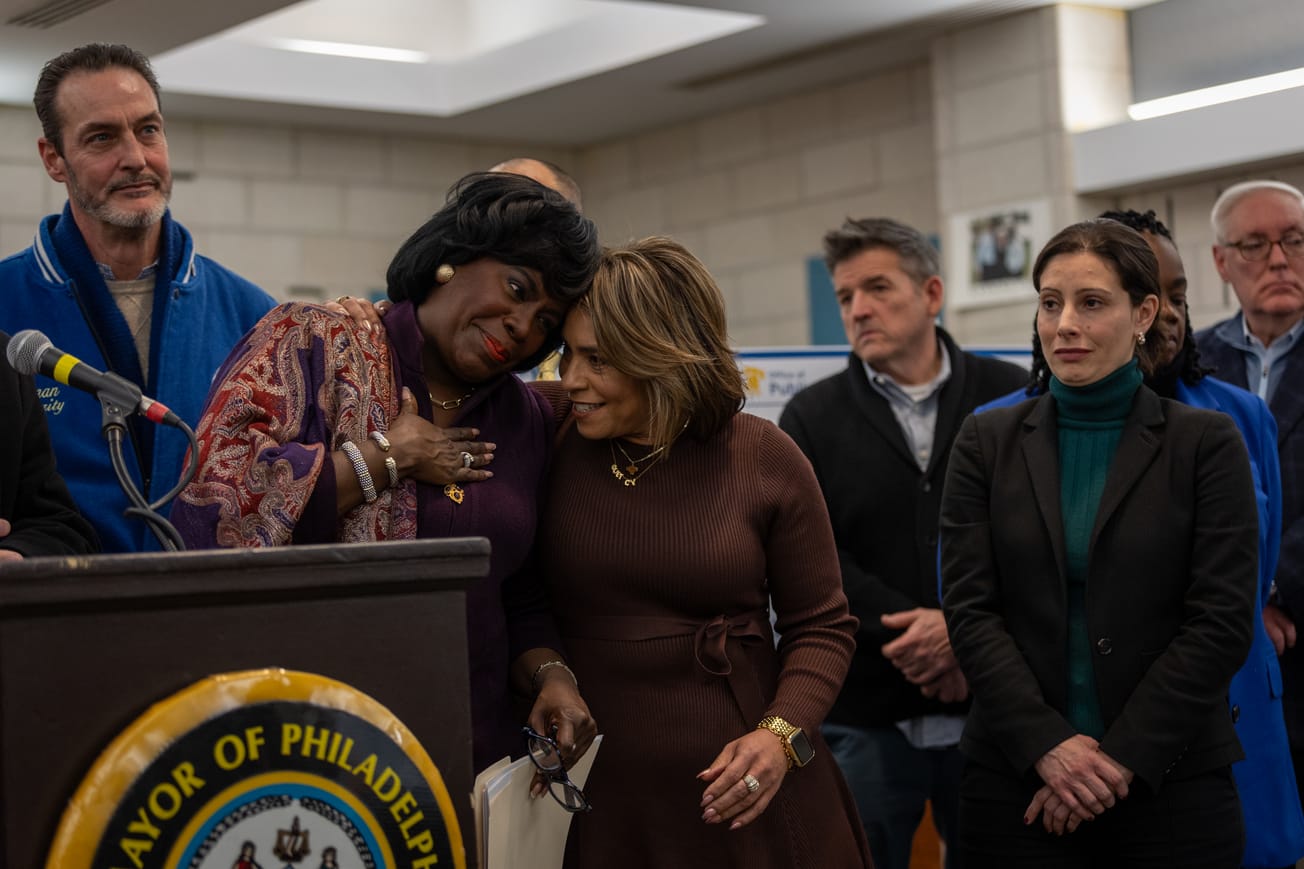

“This is just a very obvious, visceral depiction of the trauma,” said Adam Geer, the City of Philadelphia’s Chief Public Safety Director who oversees the police and fire departments. “No one should have to bear this responsibility other than us, the city.”

Geer said he began conceiving the cleanup pilot after he heard about a specific incident in Philadelphia’s Grays Ferry neighborhood.

“Someone made a complaint that after this horrible murder that occurred on the sidewalks in Philadelphia, that the grandma was out there the next day with her neighbors, with literally water and bleach and buckets, trying to clean up the aftermath,” he said. “We were horrified, frankly, that our citizens were doing this work.”

That grandma is Addie Dempsey, a 76-year-old who has had to clean up blood in her neighborhood twice. The most recent was in June 2022, the morning after her 36-year-old grandson Raheem Hargurst was shot and killed.

“We had to get that blood up,” she said. “The doctor across the street there, he came over here and helped me get it up … Bleach, water, and I swept a lot of it on the side, I swept that in the sewer.”

Under the new protocol, police officers arriving after a shooting will wait until the detective on site releases the scene and then call the dispatch center to request a cleanup. Dispatchers will call the vendor, who must arrive within 90 minutes per their contract, according to the city.

Geer believes Philadelphia is the first city in the country to hire biowaste professionals to handle the aftermath of crime scenes.

“There were certainly some jurisdictions which looked at cleaning crime scenes inside the home, which presents a whole other host of problems,” he said. “We wanted to focus on what we could easily manage as a city, on public property … we did our research and discovered that there really wasn't a roadmap for this.”

In some states, people whose loved ones are shot inside their homes can receive state funding to help hire a cleanup service. California, Florida and Georgia maintain directories of companies that do this work so that victims don’t have to do the research themselves. The Jackson County, Missouri prosecutor’s office has a special fund to repair bullet holes and other home damages after shootings.

But few cities have invested in cleaning up after homicides on the streets, said Lenore Anderson, executive director of the national nonprofit Alliance for Safety and Justice.

“It speaks directly to a broader pattern of disregard that many victims of violence, especially in urban communities of color, experience,” she said. “Far too often, what we hear is victims feel like they're completely on their own. This is just one egregious example of that.”

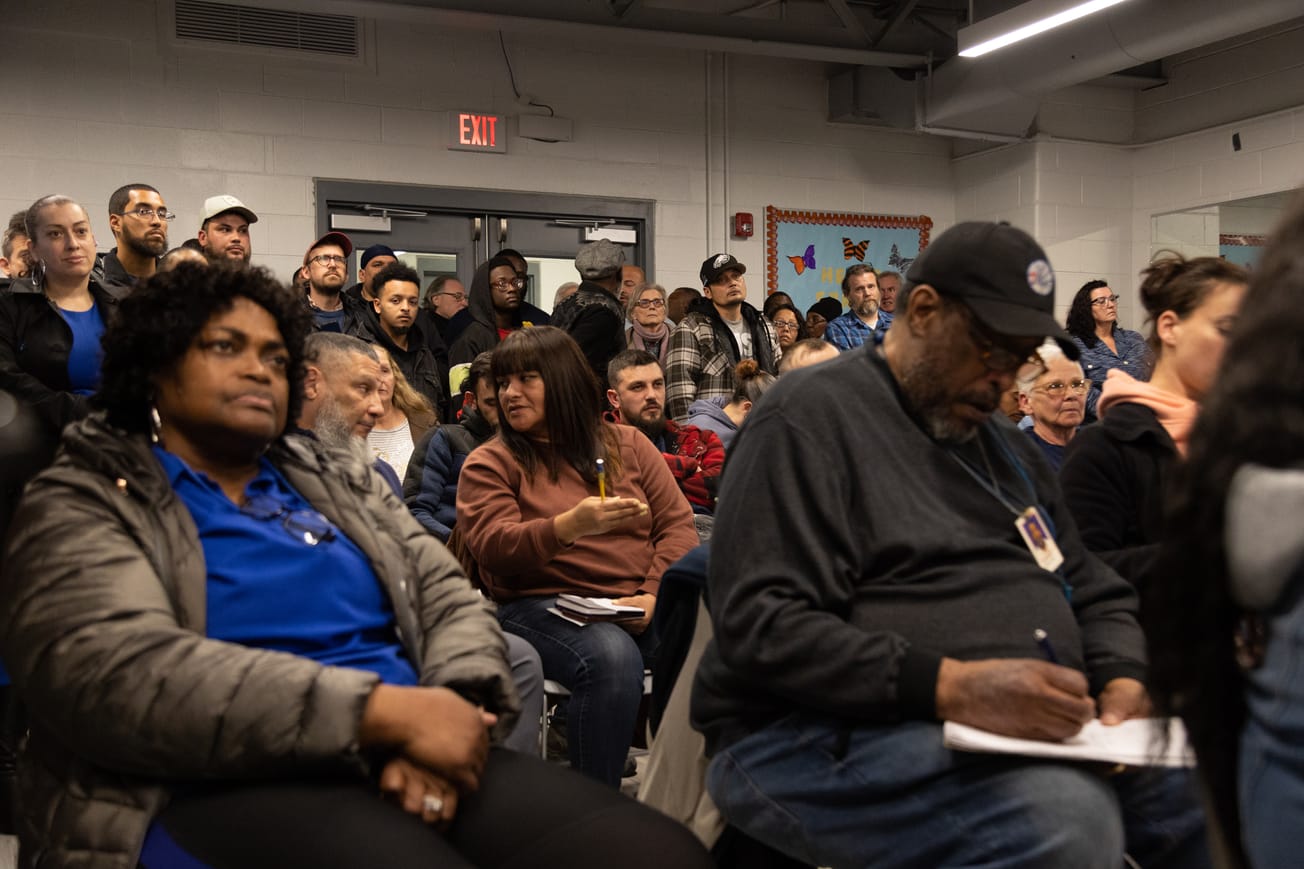

The Anti-Violence Partnership of Philadelphia first brought the issue to the City of Philadelphia’s attention in 2021 when the homicide victims’ rights group presented a report to Philadelphia City Council about the trauma experienced by residents who clean up crime scenes.

Natasha Danielá de Lima McGlynn, the group’s executive director, said she’s “elated” that the advocacy helped inspire the change. She said the city’s responsibility now is to update communities about it.

“We’re still seeing instances of this experience – it’s not going away.” she said. “And if the city is actually thinking about victims and survivors, then any type of update – people deserve to know.”

The city should also make sure that the cleanup company they’ve signed the contract with gets training on how to communicate with residents in the areas where shootings occur, said Tanya Sharpe, a professor of social work at the University of Toronto who studies the impact of homicide in Black communities.

“They’re cleaning up somebody’s child’s blood matter, brain matter. And more than likely, family members and community members are present or watching,” she said. “It not only calls for a responsibility for the city to provide the service, but it also says, ‘How are we going about providing the service in a culturally responsive and caring way?’”

Geer said the city has conducted two trauma training sessions for the vendor.

The city has allocated $500,000 dollars annually for the pilot, and plans to adjust that number as necessary based on need. The program will launch in just one district before expanding citywide.

Geer said that if the pilot goes well, the city wants to expand it to other neighborhoods and also work with residents to do more robust beautification such as removing litter and commissioning murals.

“We want them to know that this is just our commitment to really dealing with the trauma as a policy, and we don't intend to stop here,” he said.

Residents in the 25th police district who notice blood and other biowaste after a shooting can ask responding police officers whether they’ve called in the cleaning service. Officers are required to stay on the scene until the vendor shows up.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.