On Thursday, Mayor Cherelle Parker marked her 100th day in office with a visit to Conwell Middle School, where her administration announced it would arrest people for drug use, prostitution, “quality-of-life” crimes, and “other criminal acts” as part of a new five-phase initiative called the Kensington Community Revival (KCR) plan.

The KCR plan is part of Parker's executive order mandate to “Develop a strategy to permanently shut down all pervasive open-air drug markets, including but not limited to open-air drug markets in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia.”

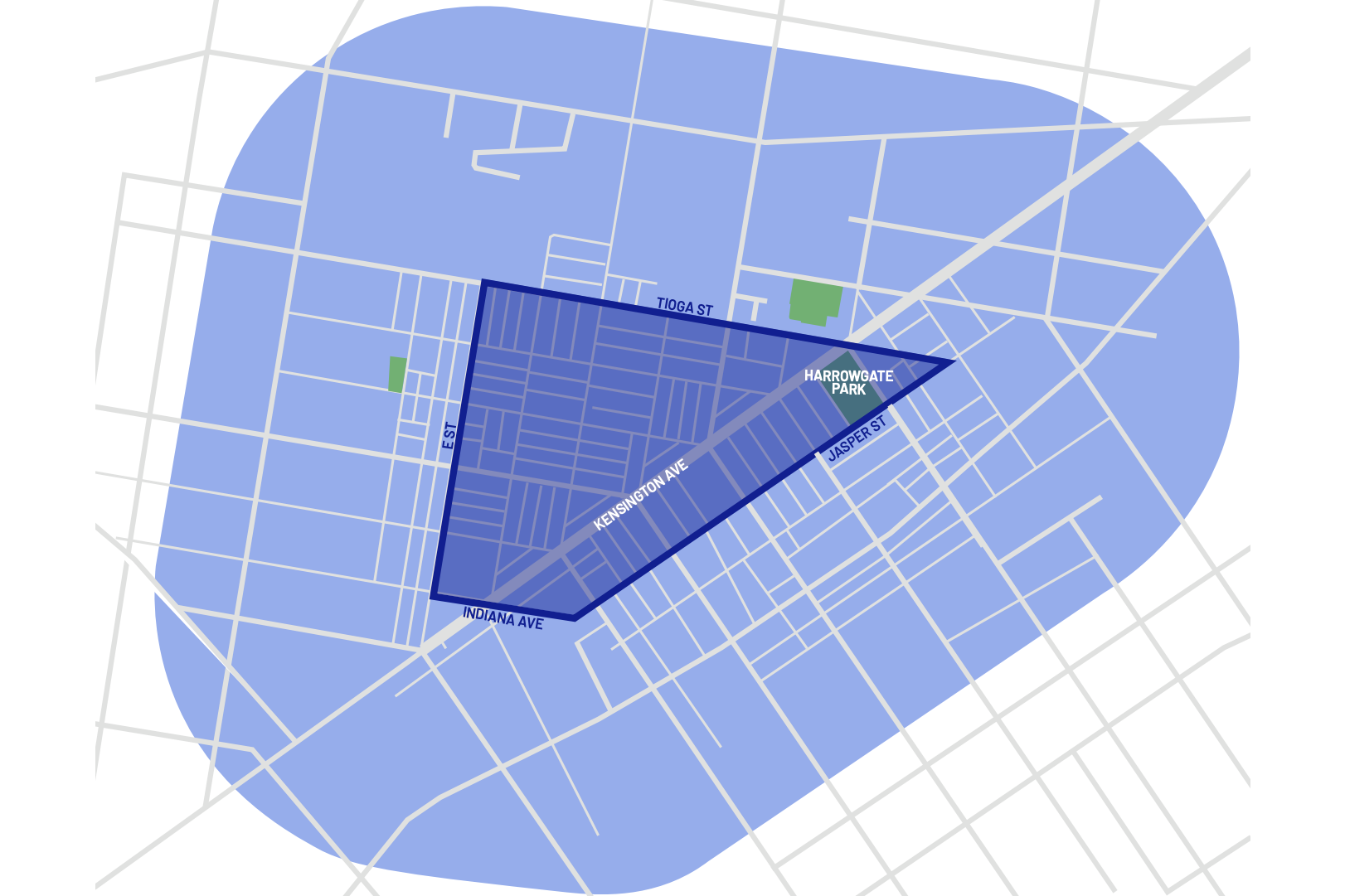

The initiative will target the area from E Street to Jasper Street and Tioga Street to Indiana Avenue, eventually expanding outward, according to Parker's 100-day report. It will begin with a “warning and opportunity” phase, which city officials describe as a final offer of services and treatment to unhoused people and those experiencing addiction.

While Police Commissioner Kevin Bethel said the first phase will begin sometime after an encampment sweep scheduled for May 8, Adam Thiel, the city’s managing director, said “we don’t have enough beds” to offer everyone using drugs in the neighborhood treatment and other services.

“This continuum of care currently doesn’t exist,” he said. “We're just not ready to say anything yet as far as having it all figured out.”

According to Thiel, the city is increasing its existing resources and developing long-term treatment and housing options. However, he did not specify which resources the city is focusing on expanding or potential sites, locations, or providers.

Thiel’s admission that the city does not have the services it needs to offer everyone treatment comes after Parker recently vowed to defund syringe exchange programs like Prevention Point and the coalition of City Council members known as the Kensington caucus began cracking down on harm reduction programs in the neighborhood.

It also follows City Council’s vote to ban “narcotics injection sites,” commonly known as supervised injection sites or overdose prevention sites, from all but one City Council district, including Kensington.

In January, the Kensington caucus also announced its plan to create “triage centers” where people would be given a choice between treatment or jail.

Thursday afternoon, just hours after Parker announced the KCR plan, the Kensington caucus introduced a new resolution to create a “Special Committee on Kensington” which – among others – has a central goal of “evaluating the effectiveness of current programs and policies.”

The resolution’s text cited a recent report from Thomas Jefferson University that found “people have waited 15 to 18 hours while going through withdraw[al] for a bed they may or may not get, and an urgency for a coordinated effort to enable real-time bed, space, level of care and program availability is much needed in Philadelphia.”

It also cited a 2019 report published by Drexel University that found Kensington has the worst health outcomes out of any neighborhood in Philadelphia, where “Kensington residents are more likely to lack public or private health insurance, smoke, have skipped a meal, and have hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, or mental health diagnosis.”

An overview of the KCR plan

According to Parker’s 100-day report, the KCR plan intends to meet the following goals:

- Identify, establish, and resource a cross-functional implementation team for Kensington

- Establish and maintain a network of community partnerships

- Secure, stabilize, and maintain the Kensington Avenue corridor and surrounding corners

- Remove open-air drug use and narcotics sales

- Remove the presence of drug users

- Eliminate shooting victims

- Improve environmental and economic conditions

The plan has five phases, including:

- Warning and opportunity

- Law enforcement & the community’s establishment of goals and expectations

- Securing the neighborhood

- Community transition

- Stability

While Bethel said the “warning and opportunity” phase would not begin until after next month’s encampment sweep, he would not provide a timeframe on its execution during the press conference.

“There's only been a handful of open air drug markets in the nation, and so there are things that could potentially happen as we go through our execution,” Bethel said. “We want to have a plan to enable us to be nimble and fluid enough to change and adjust as necessary, so I will not put a timeline on it.”

Phase 1: “Warning and opportunity”

Those living in the encampments on the 3000 and 3100 blocks of Kensington Avenue have been ordered to move by May 8. Shortly after, police will begin phase one, Bethel said during Thursday’s press conference.

The plan says police will partner with city agencies and other organizations to provide services and treatment to unhoused people and those experiencing addiction.

This phase will “serve as a warning to all who occupy this area that this will be the final opportunity to take advantage of shelter and treatment services prior to enforcement efforts that will follow Phase One,” according to Parker’s Order.

An earlier page in the KCR plan also suggests, “Drug users from the area will be removed by providing adequate diversionary services towards recovery.”

There are no details around what specific partners, programs, services, treatment, or housing opportunities are involved. Thiel said the city is still working on its triage plan.

Thiel said they are building a “system of care that literally does not exist as far as we know in this nation, it certainly does not exist in this commonwealth.”

Phase 2: “Law enforcement & the community’s establishment of goals and expectations”

The second phase of the plan involves aggressive police enforcement and a “warrant sweep in the immediate area.”

Arrests for crimes related to narcotic drug possession, drug sales, and drug use, prostitution, life quality, and other criminal acts will begin with police working one to two blocks at a time.

Officers will be wearing body cameras to document the process.

“[We’ll be] working with all of our partners, giving them the opportunity to go into treatment if they so desire, but we'll also take action on those who continue to use drugs, sell drugs, or engage in behavior that is unacceptable,” Bethel said.

City officials did not specify what classifies as a “quality-of-life crime.”

Phase 3: “Securing the neighborhood”

Police will “secure and hold” the Kensington blocks that have been cleared by the PPD. Those blocks will be patrolled to prevent “destructive, criminal behavior and nuisance activity” from returning.

The PPD will use barricades or bike racks to block the sidewalks and business corridors until areas are fully cleared. The city then plans to “beautify” the blocks and install new lighting to storefronts.

Phase 4: “Community transition”

During the fourth phase of the plan, cleared blocks will be “handed back to the rightful owners of the community and its residents.”

The city says it wants to collaborate with residents, business owners, and the “community at large” to ensure adequate funding for the neighborhood.

Through that process, the city says it hopes to establish long-term goals and a strategy for Kensington.

Phase 5: “Sustainability”

The PPD will start to shift its focus from Kensington and disperse more police officers throughout the city. However, the plan says it will also grow its mini-police substation on Kensington Avenue more permanently.

Over time, if improvements are seen, PPD plans to decrease staffing in the area.

Community perspectives

Cheri Honkala, a Kensington resident and director of the Poor People’s Army human and economic rights campaign, said the KCR plan reminds her of New York City’s War on Graffiti during the 1970s and ‘80s. She said it’s a “superficial” approach to the problem, “where the city [paints] over the graffiti,” but doesn’t address the systemic issues at the root.

“It’s not about protecting the poor and working class in Kensington, it’s about hiding the problem,” Honkala said. “And it further keeps people trapped in shame.”

Honkala has been a community advocate for the last 30 years and lives three blocks from Kensington Avenue. Her son’s father experienced chronic homelessness, lived with addiction and AIDS, and could not get the services he needed from the city, she said.

“Every three households, somebody has a brother, sister, mom that are living out on the street because they can’t get their mental health services addressed or their drug and alcohol issues addressed, or they’re stuck in jail because they can’t afford bail, or they don’t have access to affordable housing,” Honkala said of her neighborhood.

“There’s waiting lists on everything, and there’s a lot of smoke and mirrors in this city,” she added.

She said these issues are not about a “scarcity” of funding, but about misdirected priorities. Instead, she believes addiction should be treated as a healthcare issue, rather than criminalized.

Instead of funding the police, she suggests building luxury apartments for the working class and investing in nurses and social workers who can be in Kensington helping people suffering from withdrawal.

Kensington resident Alfred Klosterman is eager for change and the increased policing Parker has promised. Klosterman said he’s already witnessed police target people selling drugs on his block, which he believes is crucial for the KCR plan to work.

However, he wants the police to engage with people in a way that helps them and hopes that when given the choice, those living with addiction will choose treatment.

“The constant low-level crime is just mind-numbing, so if it can be used as a lever to get the users off the street and into treatment, great,” Klosterman wrote in an email to Kensington Voice. “It's good that enforcement only comes if there's no willingness to cooperate.”

Klosterman said that the third phase of the plan, which involves “securing the neighborhood,” looks like a challenge. He said the success of that phase will depend on social programs, anti-poverty efforts, and community-based police patrols.

Long-term, he also said that residents must be wary of gentrification, and the city needs to center community voices when it moves into the fourth phase of “community transition.”

“If rich white investors decide to rush in for a land grab once the streets are clear, we're back where we began – a dysfunctional community,” wrote Klosterman. “The city and police have to let this stage be community-driven, the residents leading the way and seeing the benefits.”

Charito Morales works in Kensington and is a registered nurse whose brother died of an overdose at El Campamento. She said she has witnessed a lot of empty promises from the city over the years.

“We don’t need more police on this type of issue,” she said. “Police are not equipped with mental health and trauma training.”

Morales, who walks around the neighborhood with a few other community members on their own behalf, connects people to resources, tries to reconnect people with their families, and hands out her cell phone number.

“You know how many people call me at 2:00, 3:00, 4:00 in the morning? I don't even know who they are,” she said.

Morales thinks the increased police presence will increase violence and “create a more aggravated situation between the people in the community and the police that right now is really fragile.” She suggested the city fund a call center to field Kensington residents’ needs instead.

Now she’s starting to inform people living with addiction of their rights, trying to get ahead of the city’s enforcement plan.

“Do you see them opening the doors for people like me in the meetings? Have you seen people in the real community that are really suffering from this crazy situation, being invited to these community meetings, invited to the city to have a conversation one-on-one with the state, with the senators, with the city officials, with the mayor?” asked Morales.

“We are angry,” she said.

*Editor's note: A previous version of this story said that Charito Morales lives in Kensington. It has been corrected to reflect that she works there.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.