Opioid settlement spending faces growing scrutiny as Pennsylvania awaits millions more

Counties battle uncertainty over funding rules while advocates and families push for an increased say in opioid settlement spending decisions.

State law requires Pennsylvania hospitals to provide rape kit exams on site. Still, Philly's three largest hospital systems have protocols for transferring sexual assault survivors to a facility that is co-located with law enforcement, receives no city funding, and is about $400,000 under budget.

Content warning: this story contains references to sexual violence, descriptions of medical examinations performed in the aftermath of sexual violence, and descriptions of interactions with law enforcement.

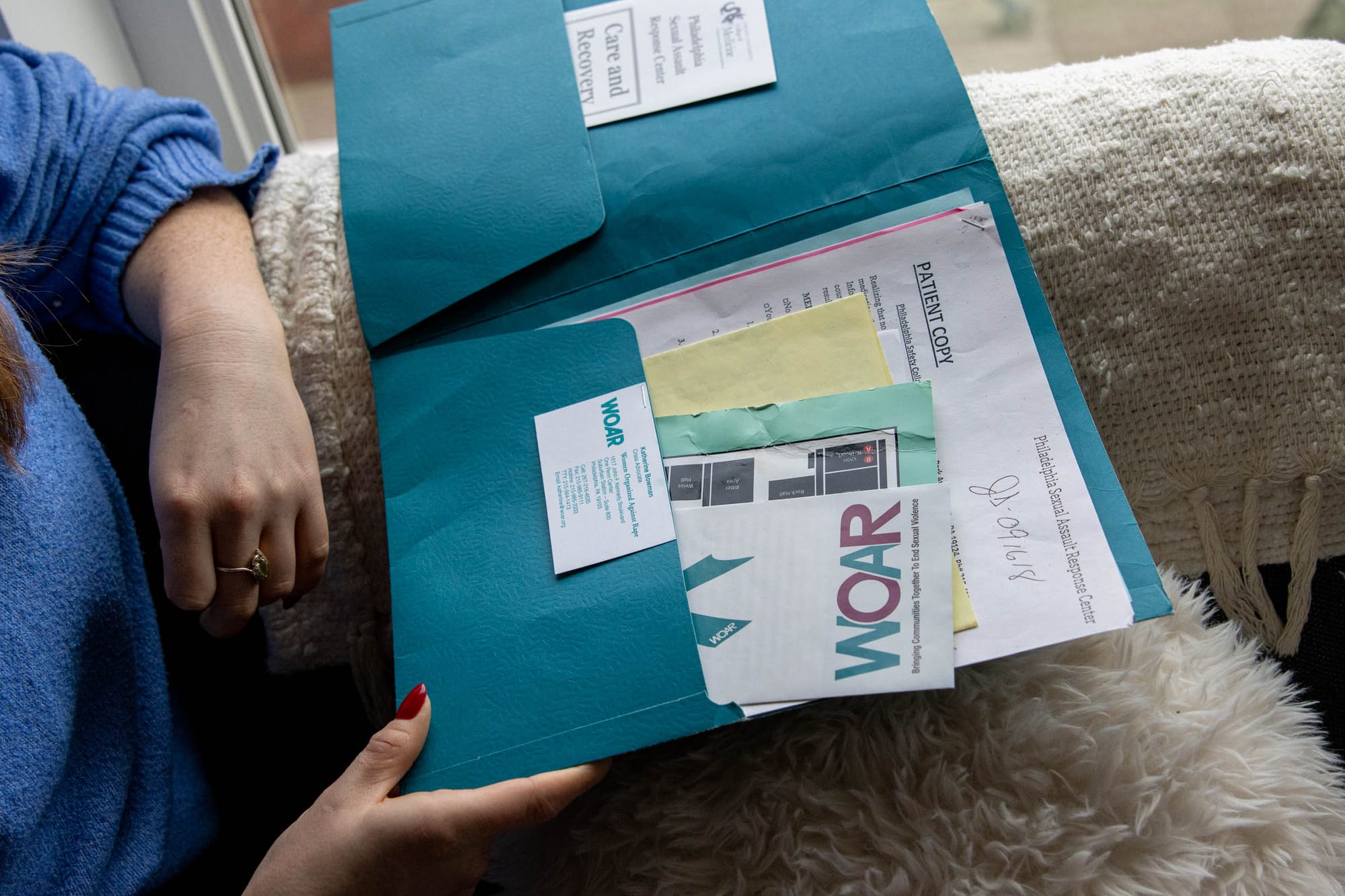

Grace Shallow walked through a parking lot toward a large, gray building complex in search of the Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Center. She’d been raped about eight hours earlier. It was a hot Sunday afternoon, and she was dragging. She carried the crumpled clothes she wore the night before in a shoebox.

A few feet in front of the entrance, a Philadelphia Police Department officer on a smoke break asked Shallow and the two friends she was with why they were there.

“It almost felt accusatory in the way he said it,” Shallow said. “It felt like a conversation with a bouncer at a nightclub … it just felt like we had to say the right thing.”

The Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Center, or PSARC, is the city’s primary location providing rape kit exams – also called SANE exams or forensic exams – following a sexual assault. It’s located inside a maze-like multi-agency building on Hunting Park Avenue called the Philadelphia Safety Collaborative.

PSARC is where cops take people who report sexual violence and where the local rape crisis center WOAR directs those who call for help.

It’s also where Philly victims ages 16 and older who show up at the emergency department are typically transferred for rape kit exams unless their injuries are severe enough to require hospitalization, according to area hospital protocols. The police often provide the ride.

PSARC opened in this location in 2013 as an alternative to crowded emergency departments – a hub where a victim could get an exam, make a police report, and receive counseling all in one place. Those who support it say it’s a way to get survivors the most specialized care available.

But some experts and advocates argue the process is so entangled with law enforcement and difficult to navigate that it’s failing the city’s most vulnerable victims.

“Individuals who have been assaulted have the right to receive care without involving law enforcement,” said Sheridan Miyamoto, a nurse practitioner and nursing researcher at Penn State University. “So if a police car is your ride, and that’s the thing you want to avoid … those are huge barriers to seeking care, the care they deserve.”

Philadelphia is the only jurisdiction in Pennsylvania that provides rape kit exams in a single building co-located with law enforcement, according to multiple local and statewide advocacy sources. Pennsylvania law requires hospitals to provide rape care in the emergency room, and multiple Philadelphia health systems have received citations from the state health department for violating that policy.

The center is also about $400,000 under budget, according to its clinical director, Allison Denman. She said the reimbursements the state offers for rape kit exams fall far below the actual cost of providing them, and the funding Drexel University provides for overhead doesn’t cover basics like new medical equipment.

PSARC receives no city funding, according to a city spokesperson, despite providing for the vast majority of those who seek care following a sexual assault in Philadelphia. Denman’s request for funding in the fiscal year 2025 budget, made in collaboration with the city’s Office of the Victim Advocate, remained unmet in the mayor’s budget proposal released last month.

The mayor’s administration declined to comment on the ask but said the mayor and her administration “care deeply about issues around sexual assault” and that more information “will be discussed” throughout the budget process, which ends in June.

Denman keeps the center running with one full-time program director, a part-time employee, and a rotation of 25 on-call nurses on a budget of less than $425,000 per year, plus an ad-hoc medical director who doesn’t take a salary.

“We’re kind of the ugly stepchild in the middle of all of this, and we’re the slapdash fix for a much larger systematic challenge,” Denman said.

Shallow got to PSARC in a Lyft after calling the WOAR hotline for guidance. She knew to call WOAR from seeing flyers around her college campus at Temple University.

“It looks like a police station, and it is half a police station,” she said. “That was jarring because the title Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Center invokes the image of maybe something more holistic than a police station.”

It looks like a police station, and it is half a police station.

Farah Sayed said she and a friend found PSARC by searching online after their attempts to seek help from student health services at the University of Pennsylvania failed.

Sayed, now 22, was a student there when she was sexually assaulted last spring. She said finding a good transit option was difficult since PSARC doesn't show up on Google Maps, and it takes between 40 and 50 minutes to get there via public transit from Center City. So they called a ride instead.

"It's just inconvenient and kind of stressful to plan out that trip if it's a place that you haven't been in, especially since it's within a police station," she said. "If this is difficult for me, it is certainly much more difficult for a lot of other people."

In Pennsylvania, several pieces of legislation regulate resources and protections for sexual assault survivors.

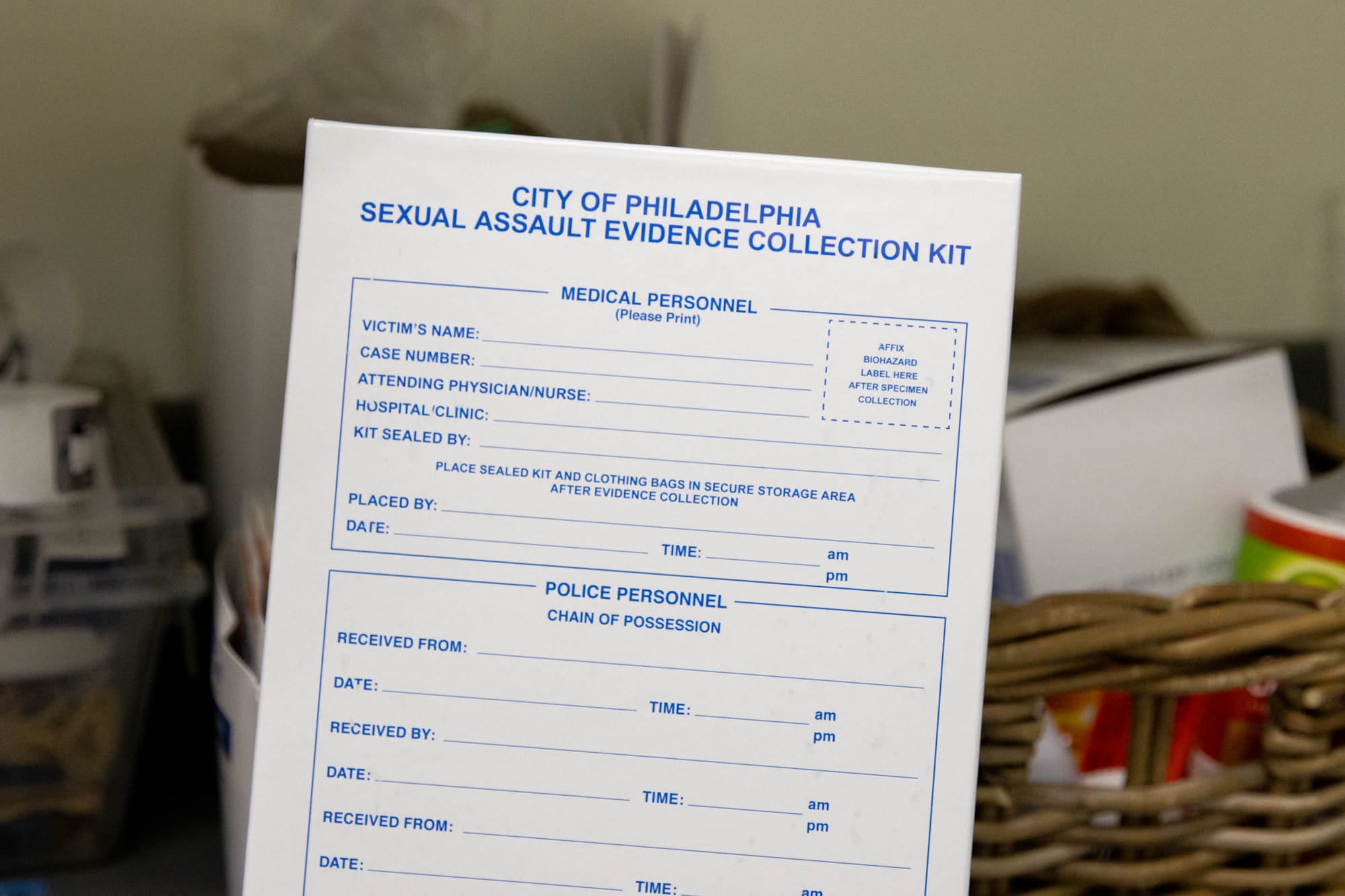

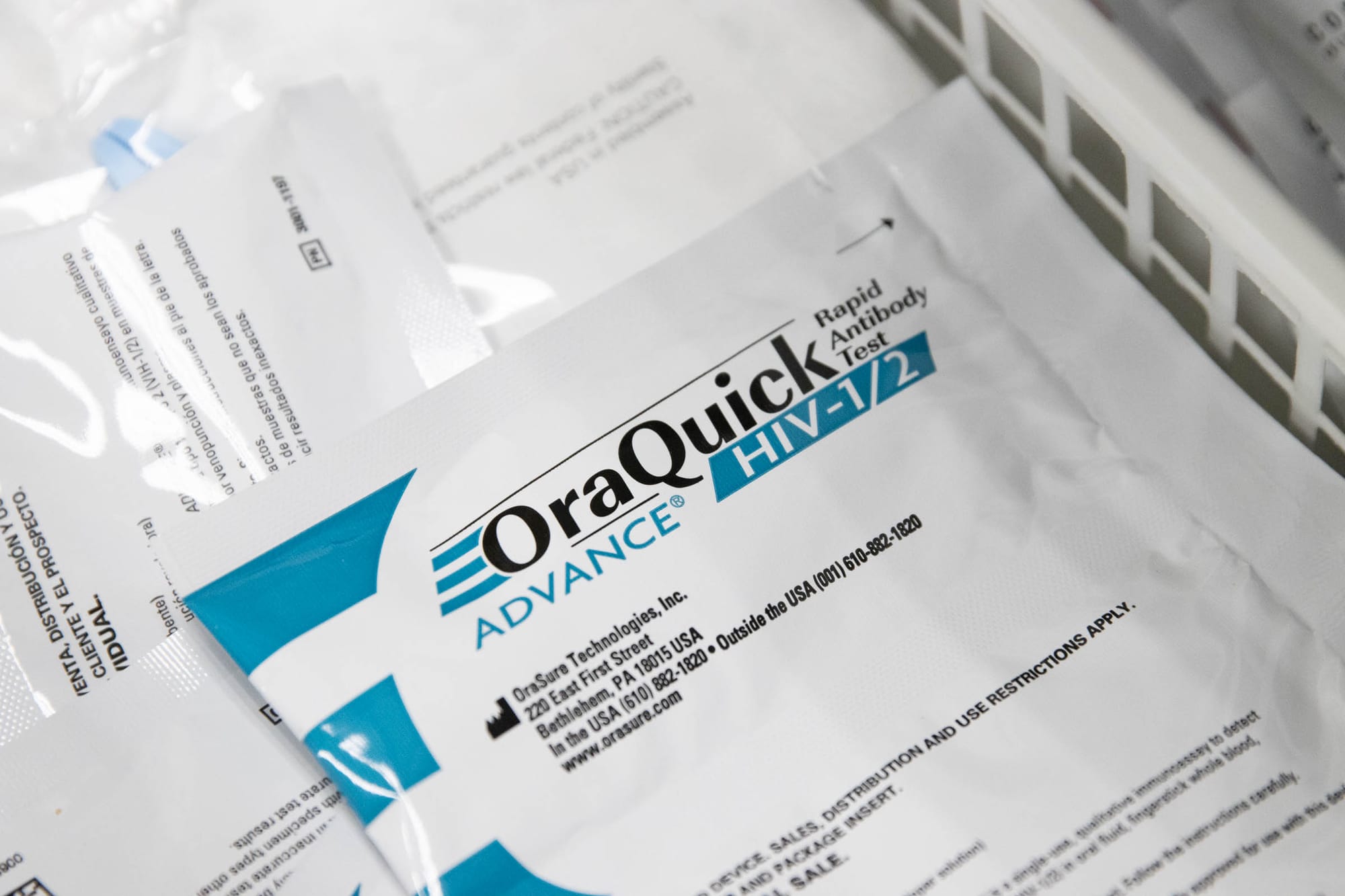

At the state level, the Sexual Assault Victims Emergency Services (SAVES) Act requires hospitals to provide free rape kit examinations. It also entitles survivors access to medications, including HIV and sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention and emergency contraception, plus STD testing. The state’s Sexual Assault Testing and Evidence Collection Act provides survivors with the right to have their rape kits processed as evidence of a crime, which they can do with or without their names attached to the kit – their choice.

Meanwhile, at the federal level, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) and the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) entitle sexual assault survivors to various patient care and financial protections.

Although EMTALA is not specific to sexual assault services, it was designed to prevent a practice known as “patient dumping,” or sending patients who can’t pay for their services to other facilities – such as PSARC – without first screening, stabilizing, and receiving a patient’s written request for a transfer. Under VAWA, the other federal policy regulating resources for sexual assault survivors, hospitals are prohibited from charging patients for rape kit exams, and survivors are entitled to victims’ compensation.

But Denman says Philly hospitals aren’t providing sexual assault survivors with the care required by these laws, and her efforts to talk to advocates, hospital representatives, and the state’s health department about compliance have all fallen flat.

“They have no idea about these laws, and nobody at the state level has earnestly been doing their due diligence in connecting the hospitals with this nature of compliance,” she said.

While the federal government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services surveys hospitals for compliance with federal regulations about once every three years, no statewide agency proactively audits hospital compliance with state regulations, such as the SAVES Act. As a result, the state’s health department relies on self-reported complaints to trigger state-related compliance investigations, which requires patients and other providers to understand forensic patients’ rights, know how to file a complaint and have the bandwidth to do so.

The Pennsylvania Department of Health confirmed that hospitals are required by state law to provide rape kit exams on site, unless a patient asks to be transferred elsewhere or declines an exam. The department said Philadelphia hospitals that transfer medically stable patients to PSARC for the rape kit exam “may be” in violation of state code.

Still, Philadelphia’s three largest hospital systems – Jefferson, Penn, and Temple – all have protocols for transferring patients for rape kit exams to PSARC. And two of those hospital systems have past citations from the health department for noncompliance with meeting the minimum requirements for sexual assault emergency services.

The health department cited Temple University Hospital for related noncompliance most recently in 2018 and Temple Health’s Chestnut Hill Hospital as far back as 2011, according to the department’s patient care quality assurance records. Jefferson’s Northeast Hospital was also cited for violating SAVES regulations in 2013.

According to the state’s quality assurance records, Temple “failed to ensure victims of sexual assault are provided a medical forensic examination within the Emergency Department,” the documents said. The facility also failed to stock state-approved rape kits to collect forensic evidence.

In staff interviews cited in the 2018 document, Temple “sends all discharged Emergency Department sexual assault patients to a regional, contracted victims response center, for further examination and collection of forensic evidence.” The records also noted that “contracted victims response center staff will perform forensic examinations on admitted inpatients within the facility and will perform examinations in the Emergency Department ‘only if requested by the police.’”

When the state investigates a facility and finds it noncompliant, they develop a correction plan with the facility, according to a health department spokesperson. To resolve Temple’s noncompliance, both the health department and hospital agreed on a correction plan.

Temple's plan included ordering rape kits, revising their sexual assault policy, and providing education and training for hospital staff on evidence collection. It also required a “100% review of all patients presenting with complaints of sexual assault,” and chart audits “to ensure that all patients with a chief complaint of sexual assault have had the required screening completed.” It stated that “this monitoring will continue through December 2018” because sexual assaults are “a low-volume presenting complaint.”

But a Kensington Voice review of more than 2,000 records found a weak record of health department oversight following initial sexual assault compliance citations, including Temple’s 2018 violation.

Despite the suggestion that the health department would monitor Temple’s patient charts for compliance through December 2018, they revisited Temple in March 2018 and found the hospital compliant with no additional follow-up beyond that date.

“While a hospital would not be required to have implemented a corrective action addressing noncompliance before its accepted corrective action date, it is deemed compliant if the Department of Health resurveys a hospital and it is found ‘compliant’ before its monitoring date,” said Neil Ruhland, a spokesperson for the health department. “This can occur when a survey has both a state and federal component.”

In the Pennsylvania health department’s role as a state survey agency for the federal government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Ruhland said the department must meet certain federal deadlines and is encouraged to coordinate federal and state inspections – which was the case regarding Temple’s March 2018 follow-up visit.

“The department was able to determine the previous state compliance issues had been addressed by the corrective actions that had been implemented by the facility at that point,” he said. “Thus, the facility was found to be in substantial compliance with the department’s regulations.”

In other sexual assault-related noncompliance cases, including one from Jefferson’s Northeast Hospital in 2013 and one from Temple’s Chestnut Hill Hospital in 2011, there are no records of health department follow-up beyond the initial noncompliance citations.

Meanwhile, at the federal level, CMS has cited several Philadelphia hospitals, including Temple and the University of Pennsylvania, for EMTALA noncompliance as recently as 2022. However, no Philly hospitals have been penalized for those violations – for which CMS can fine them and disqualify them from Medicare participation. Those records do not include whether the patients affected were seeking sexual assault aftercare.

Denman says that the government’s lack of punitive action enables hospitals to remain out of compliance since “they won’t do anything until they get in trouble for it.”

“One of the ways that we promote violence or permit violence in our communities is by not assuming responsibility and providing competent care,” she said.

One of the ways that we promote violence or permit violence in our communities is by not assuming responsibility and providing competent care.

According to a spokesperson for Jefferson Health, patients who disclose a sexual assault are medically cleared and then “transferred via PPD (Special Victims Unit) to the PSARC campus.” Jefferson did not respond to multiple requests for comment when asked directly about their policy’s compliance with the state health code.

At Temple University Hospital, after emergency room patients are medically cleared for transfer, staff arrange “a transfer to the Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Center for additional counseling and an exam,” according to a November email from a hospital spokesperson. However, when pressed about compliance, hospital representatives said in a follow-up email in March that Temple “arranges for the patient to have an exam, which includes an opportunity for the patient to receive a sexual assault examination at the hospital.”

While the University of Pennsylvania website states that “forensic rape examinations cannot be performed at any local hospital unless the victim is being treated there for injuries that are so severe they are considered medically unstable,” a Penn spokesperson wrote in a March email that forensic examinations “can be completed both in the hospital setting or at PSARC, depending on the specific care needed for each patient.” They said their policy is in line with state law.

According to Kate McCale, director of compliance for the Hospital and Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania, hospitals are likely within state regulation if they get survivor consent for any transfer to an alternate site and provide the exam in-house to those who request it.

“If the patient is in a place where they don’t want to be transferred, they don’t necessarily have to be,” she said. “They can have that forensic exam on site at whatever hospital they present at.”

Neither PSARC nor the health systems track how many victims are referred from the emergency room to the center, or how many decline transfers.

Miyamoto says “there aren’t great data” that capture how often Pennsylvania emergency rooms turn away sexual assault survivors, but she’s heard “that people do get turned away.”

“[Hospitals] could do a quick, cursory exam just to make sure that they don’t have any life-threatening problems that need to be addressed and then say, ‘We don’t do sexual assault exams, we don’t do evidence collection – you need to go to X place,” she said.

According to Babs Sheaffer, director of medical advocacy for sexual violence prevention organization Pennsylvania Coalition to Advance Respect (PCAR), transferring patients away from the hospital increases the risk that they will not seek care once referred to PSARC because it requires an extra step during an already stressful experience.

“The chances of somebody going from one hospital and then being told they should go somewhere else, I do not know how many people follow through with that,” she said. “Who falls through the cracks?”

The double glass doors of the Philadelphia Safety Collaborative deposit visitors at the Philadelphia Police Department Special Victims Unit (SVU) reception desk. It’s plastered with police department flyers and a laminated sign prohibiting firearms. The desk is empty, and one of the signs says, “Ring doorbell for service.”

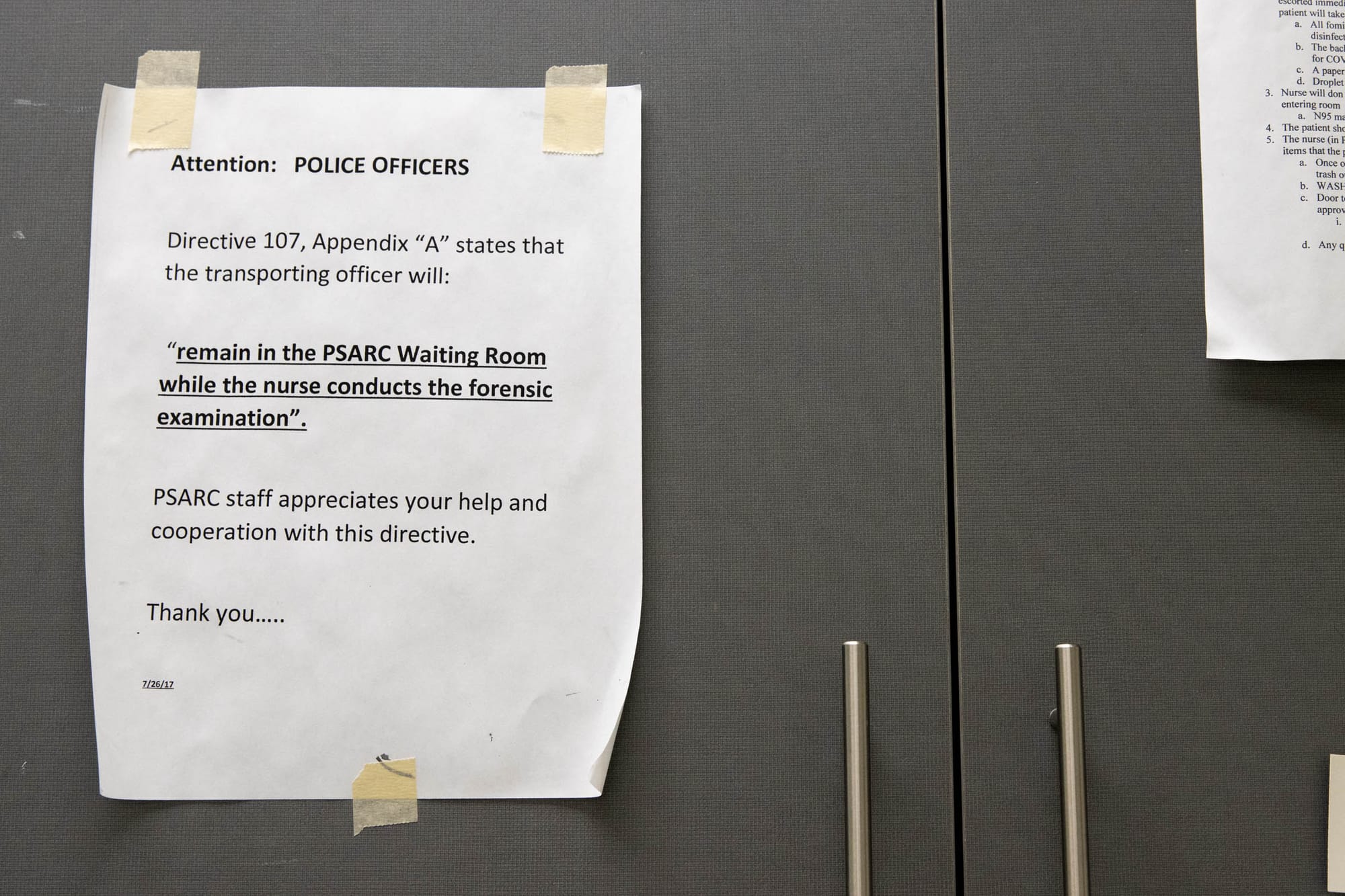

Only by speaking with an officer is a rape survivor taken down several long, beige hallways to the PSARC office where exams take place. If they’re not filing a police report, survivors must state they want to receive an exam anonymously when they enter the building. Otherwise, they meet with an SVU detective in a private interview room.

According to Denman, PSARC staff are in the building during weekday business hours, from 6 a.m. to 5 p.m. On evenings and weekends, survivors wait in a small, fluorescent SVU waiting room until a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner, or SANE nurse, arrives — usually within one hour — to take them back to PSARC. Most patients come in on weeknights after 6 p.m. and “mornings or late nights on weekends,” Denman said.

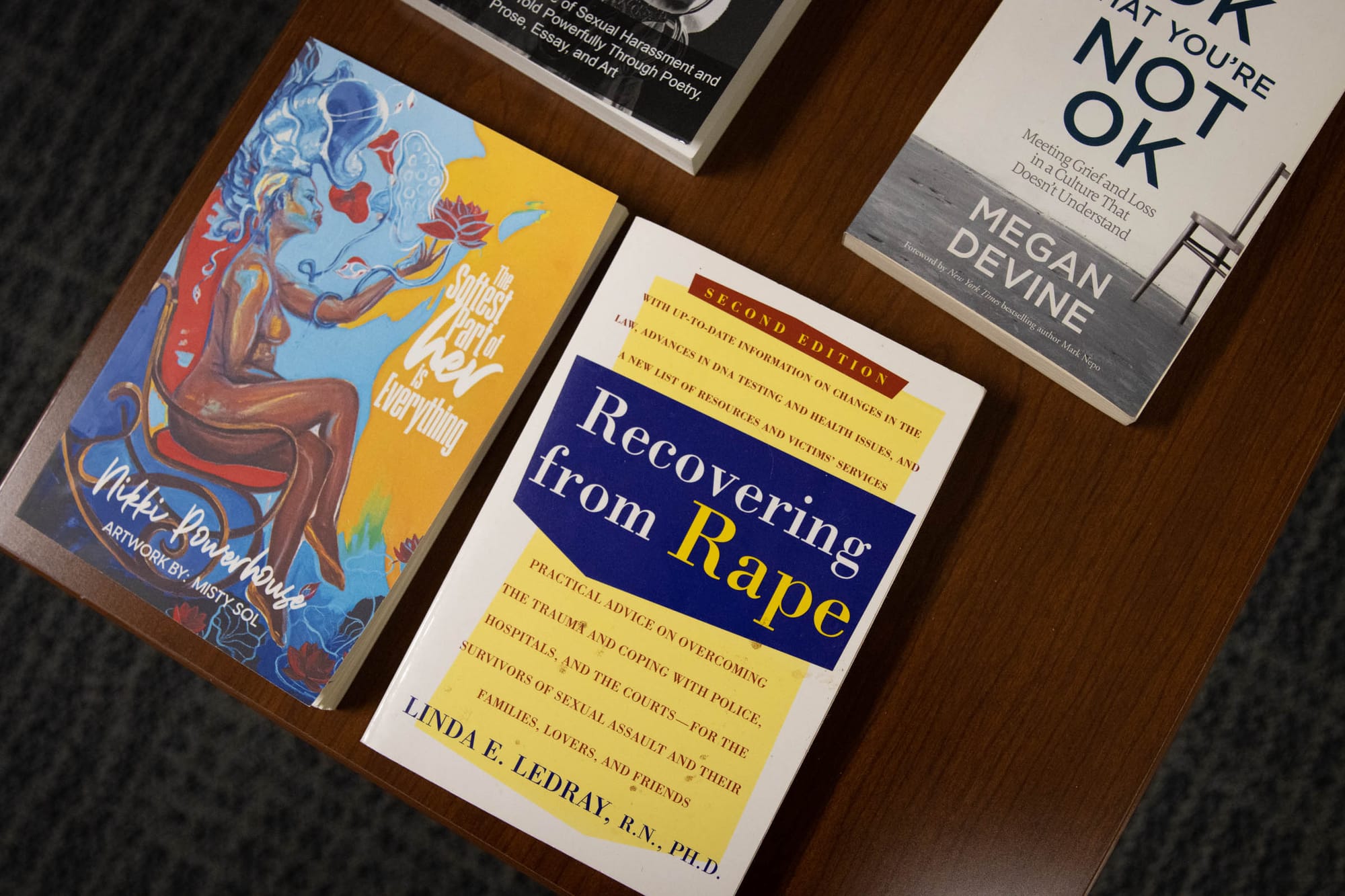

The PSARC waiting area is quiet. It’s carpeted and furnished with chairs. The coffee tables have magazines and books about life after rape. There are pamphlets about human trafficking and sexual violence.

Denman tries to make the space as comfortable as possible for survivors. She offers snacks and water. She also puts out calls for new and gently used clothing donations so visitors can replace items they were wearing when they were raped.

She handles those details between conducting exams (she’s a SANE nurse), providing expert testimony in court, spreading public awareness about PSARC, and raising money to cover the center's overhead costs.

Caring for sexual assault victims is difficult work, Denman said, and she and others do it with “absolutely no support scaffolding.”

“This place is built on bones, and the only way we’ve been able to operate is the revenue from [the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency] (PCCD), which is not stable,” she said.

In 2022, PSARC nurses performed 321 rape kit exams in the center and 11 exams at local hospitals in cases where victims were not stable enough for transfer, according to the center’s most recent self-published annual report. Since 2011, PSARC has performed over 5,000 total rape kit exams.

PCCD reimburses the cost of exams, up to $1,000 per exam. Denman said Drexel University, which helped launch the center in 2011, covers most of the overhead costs.

Exams can involve checking a survivor’s body for external and internal injuries and taking blood and urine samples, swabs of body surface areas, and pieces of hair to collect evidence for a rape kit. They take somewhere between 90 minutes and six hours, depending on the details of the assault, according to multiple advocacy organizations. They’re often performed by a SANE nurse who has received 40 hours of training on the procedure, but some hospitals have ER nurses do them instead.

Survivors don’t have to report rape as a crime to get a free rape kit exam. However, all kits are handed over to law enforcement regardless of whether a crime is reported. When survivors request a rape kit exam without reporting a crime, the kit is stored without a survivor’s name attached to it. That way, police can enter the results into a federal database of convicted offenders, unsolved crime scene evidence, and missing persons. Survivors who initially ask for an anonymous rape kit exam can still go back and report rape as a crime at a later date.

Denman has been advocating for better pay for on-call SANE nurses. She also wants area hospitals to kick in funding for rape kit exams performed at PSARC to help offset the center’s costs.

“Adjusting the hospital contracts to include a subscriptive overhead fee for PSARC as the total replacement of SANE care in the city will hopefully produce enhanced collaborative support from the local emergency department community as contracts renew,” reads the center’s most recent annual report.

Carol Tracy, who worked with the Women’s Law Project for three decades before retiring from her post of executive director in 2022, was part of the group that conceived PSARC. She said having a dedicated facility for rape kit exams is a best practice because it gives survivors access to the “ongoing competence” of Denman and her team.

“They see people, it’s in a quiet setting, and it’s so highly professional. But it’s not funded properly,” she said. “The advocacy community, we did not know that until Allison brought it to our attention.”

They see people, it’s in a quiet setting, and it’s so highly professional. But it’s not funded properly.

Denman tries to notify people about PSARC’s services by attending health resource fairs across Philadelphia a few times a year.

“People really have forgotten about us,” she said. “A lot of people don't know that we exist … so when I go to outreach events by my little old self, boots on the ground with my open rape kit … I just stand there and say like, ‘Hey, who wants to learn about PSARC?’”

Survivors who arrive at PSARC may choose to have an advocate from WOAR, Philadelphia’s rape crisis center, present for the exam. WOAR’s satellite office in the Philadelphia Safety Collaborative is staffed 24/7 pending staff illness, said WOAR clinical director Christine Kannegiser.

Kannegiser said the Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Team (SART), which is comprised of WOAR, PSARC, the SVU, the PPD’s Office of Forensic Science, and the District Attorney’s Division of Family Violence and Sexual Assault, has discussed the possibility of putting a WOAR staffer at the building entrance instead of a police officer.

“We are about to enter a phase where we hope to address systemic gaps like this one,” Kannegiser wrote in an email when asked about the police presence at the front desk.

Lieutenant Stephen Biello of the Special Victims Unit said the reception area is overseen by SVU staff because it’s where victims of all SVU crimes – including children – go to report. He encourages sexual assault survivors to use that option.

“It’s a traumatic thing, but there’s also an offender,” he said. “We would hope that if the victim comes to terms with it, they’d want to tell their side to the police.”

But having to go through law enforcement to get to medical care is likely to deter anyone who has prior trauma related to police, said Teena Weisler-Vega, a services coordinator at Kensington nonprofit Prevention Point. Most of the women she interacts with have a substance use disorder and engage in sex work to pay for food, shelter, or other basic needs.

“There’s so many levels of fear,” Weisler-Vega said. “Somebody just experienced sexual assault, but then, ‘They’re gonna run my name, they’re gonna find out that I have this and that,’ like it’s just so much. To them, it’s not worth it.”

Two in three victims of sex crime don’t report to police, according to the Rape and Incest National Network. The number one reason for that is fear of retaliation, according to the group’s statistics. People who engage in sex work are among the most likely victims of sexual violence and the least likely to report, according to multiple studies.

“It’s really challenging for folks in Kensington specifically to feel safe going to law enforcement to report a sexual assault,” said Heather LaRocca, director of Kensington organization New Day to Stop Trafficking. “I don’t think they believe that they’ll be taken seriously. It also is just something that they unfortunately have experienced so often … they just don’t believe that people care.”

Outreach workers and drop-in center managers at New Day said they had never heard of PSARC. If someone disclosed a rape to them, they would bring that person to the hospital, they said. They noted an overall lack of accessible medical, mental health, and related services for women in Kensington who experience sexual assault.

“I would just imagine that if it was presented as ‘We can transport you to this other place to do a rape kit’ they would just say ‘No,’” said LaRocca, noting that victims who use drugs might also be wary of going into withdrawal during the rape kit exam process. “Especially for our folks in Kensington because they’re going to be getting sick.”

At Project SAFE, an organization for people engaged in sex work, a resource list states that all free rape kits are available at “the Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Center (PSARC), also known as the Special Victims Unit.”

Catalyst G., one of the Project SAFE organizers, said they don’t know of any members who have ever gone to PSARC for help.

“It’s kind of bizarre that it exists the way it exists,” said Catalyst, who asked to be identified by first name due to the nature of their work.

All rape kit exams used to take place at Philadelphia General Hospital in West Philadelphia. When it closed in 1977, South Philly sexual assault victims were sent to Jefferson Health, and North Philly victims to Temple University Hospital’s Episcopal campus.

“Police had a line through the middle of the city,” said Kathleen Brown, a University of Pennsylvania nursing professor who was part of the group that conceived PSARC. “And if a sexual assault happened on one side, you went to one hospital, and if it happened on the other side, you went to a different hospital.”

Brown said she and other advocates wanted to move sexual assault care out of the emergency room because victims were having to wait long periods in a chaotic environment.

“If you’re a victim of rape, and you’re not severely traumatized physically, which is usually the way it is, they’d just let you sit ‘till they can get to you,” Brown said. “It was me who said, ‘We can’t do this to the victims’.”

Brown said they first established PSARC at Temple University Hospital’s Episcopal Campus because SVU already had a designated space there. When the PPD’s SVU got moved to “a nice new building,” she said the group decided to move all rape kit exams to that location, too.

Michael Boyle, who serves as PSARC’s program director, was an SVU supervisor for 20 years and was part of the group that created PSARC.

“One of the large issues we dealt with was the delay of treatment in the hospital EDs,” Boyle wrote in an email. “Could it be done faster, more victim-centered and more efficiently for all necessary agencies? That’s the genesis of how PSARC came to be.”

Supporters of the central hub model say the ideal is for survivors to show up directly to PSARC and not have to go to the hospital at all.

“We hear of lots of incidents where somebody just may sit for hours in the emergency room while maybe the emergency department is trying to figure out if there’s somebody that might have experience that could do the case,” said Miyamoto.

Brown believes rape victims should only be seen by SANE nurses.

“I don’t want a nurse taking care of rape victims if she’s not very comfortable with inserting a speculum,” Brown said. “There wasn’t really anybody at the table who thought that [victims] just should be allowed to be seen anywhere they go.”

Still, Miyamoto said people will always show up at the hospital for sexual assault care, and facilities must be able to treat them even if SANE nurses aren’t on site.

“Emergency rooms are the right spot because it’s where the public knows to go when they’ve been harmed,” she said. “We should treat those things like the emergency they are and put the right specialists in place.”

Emergency rooms are the right spot because it's where the public knows to go when they've been harmed. We should treat those things like the emergency they are and put the right specialists in place.

Sayed said she would have preferred to get her rape kit exam in a medical setting.

“Any health care facility like a hospital, every clinic, urgent care, those types of entities are kind of spread out anyway,” she said. “Those are places where people would intuitively think to go to.”

The International Association of Forensic Nurses and the Emergency Nurses Association issued a joint position paper in August 2023 stating that emergency nurses should be trained to care for and assess victims of sexual violence, and that hospitals should strive to use a SANE wherever possible.

Kannegiser, from WOAR, said that exams should ultimately be offered at both hospitals and PSARC.

“What’s most ideal is the survivor is being seen by the most informed professional that’s trained in doing the forensic exam to reduce the retraumatization that can happen, within the quickest amount of time,” she said. “If that were to be a hospital and they’re there without the transport need, great. I don’t know if that’s always the case, unfortunately.”

More than five years after Shallow’s assault, she still remembers how she felt in the SVU waiting room. No PSARC staff were on site on Sunday afternoon when she came in, so she had to wait up front in the SVU.

She said she waited six hours for someone to take her back for the exam, and at one point, there was another woman she thought was waiting to see either the police or PSARC in the room with her.

She hadn’t slept or eaten for over 24 hours. She was thirsty and her phone was dying, so a friend showed up with a backpack filled with phone chargers and bottled water.

“It felt like a mini prison,” she said. “We just sat there. Just kind of stared at the floor there. It just feels like a dark place to be when you’re already kind of losing your sense of reality.”

Emergency rooms are the right spot because it's where the public knows to go when they've been harmed. We should treat those things like the emergency they are and put the right specialists in place.

A patient waiting that long to go back to PSARC “would’ve been a once-in-a-lifetime thing,” Denman said. She said the delay might have been a transportation issue on the nurse’s end.

Sayed said she went in for an exam on a Monday morning and sat in the SVU waiting room for two hours before someone took her back to PSARC.

“They have this bright colored wall, and then like some chairs,” she said. “It’s just like a room. It’s kind of just like a box.”

She also said “little stuff” in the moments of rape aftercare matters.

“Having real underwear, that would be really nice. Because then you’re not wearing this paper disposable thing,” she said.

The center currently provides one-time-use linen “OB” panties, according to Denman, unless an outside organization donates new cloth undergarments.

“If there was a lot of money, that could be really helpful for people who want [them] and just make them feel better leaving,” Sayed said.

Shallow’s experience at the Philadelphia Safety Collaborative still bothers her to the point that she struggles to sit in doctor’s offices, which reminds her of the waiting room. She wrote about her frustrations three years after that visit.

“It felt like the world flipped upside down,” she said. “It just felt like everything was wrong there.”

However, she did credit the two WOAR advocates who met her there – one of whom identified as a survivor – as being “really helpful.”

“They were the most helpful people I talked to that day,” she said. “And they made a point of explaining what was going to happen when I was called and what the exam exactly consisted of, what the medical procedure was going to be.”

Denman said in a text message that now that WOAR employees are more present in the building and the Sexual Assault Response Team is actively “roadmapping” how to make the waiting time “more comfortable and consistent for survivors coming through SVU.”

Shallow thinks the best possible option for survivors who need rape kit exams would be a transit-accessible building – or several – with no ties to law enforcement. The building should have a waiting space that’s designed to be calming for people in a state of trauma.

“A light blue room with fluffy couches and pillows and tissues and chargers,” she said. “Things that anyone would need if they’re going to be sitting and waiting somewhere … anything that could make people feel informed and comfortable from the minute they walk in, would be much better.”

She also noted there is no ideal place for getting care after sexual assault.

“The hard thing about creating a resource for reporting or exams, whatever the intentions are behind it, it’s always going to be a traumatizing place for people,” Shallow said. “[PSARC] was more traumatizing than it needed to be. But it’s always going to be a place where people never want to go again.”

Shallow, now 26, lives in an airy Philadelphia apartment with her two cats, Noodle and Freddie, and a collection of cat-themed mugs with slogans like “Catitude” and “I GATO go.”

She sought therapy a month after her assault to process some of the anger and grief she’s felt since the rape and her day at the Philadelphia Safety Collaborative. She still sees the same therapist today.

“If you can find joy in your life after you experience things like that, whatever other pressure you put on yourself doesn’t matter,” she said. “If you’re able to feel truly content in certain moments and be happy, I think that’s a radical act on behalf of survivors.”

https://drexel.edu/cnhp/practices/psarc/

Non-emergency phone: 215-800-1589

Emergency (for on-call sexual assault nurse examiner/SANE): 215-425-1625

Contact: Email Allison Denman directly at ald376@drexel.edu

Services offered: forensic medical evaluation, injury documentation, forensic photography, pregnancy prevention, sexually transmitted infection prevention, HIV prevention, follow-up care, court testimony, victim advocacy linkage

https://www.woar.org/

Hotline: 215-985-3333

Services offered: counseling, human trafficking support, prevention workshops, phone or on-site advocacy during exams

https://easternusa.salvationarmy.org/eastern-pennsylvania/greater-philadelphia/new-day-drop-in-center-1/

Services offered: case management, housing referrals, showers, daily meals, art and yoga groups

https://pcar.org/

Services offered: rape crisis center directory, legal information, advocacy opportunities

https://projectsafe.dreamhosters.com/

Services offered: supplies, advocacy, weekly group for sex workers

This story was published with the assistance of the Journalism and Women Symposium (JAWS) Health Journalism Fellowship, supported by The Commonwealth Fund.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.

Free accountability journalism, community news, & local resources delivered weekly to your inbox.