On a recent winter morning, Paul sat in a white plastic folding chair on a Kensington Avenue sidewalk near Indiana Avenue. His blue eyes were alert, and he wore a sturdy jacket against the January cold.

For 20 years, he’s been cycling between prison and the streets in Kensington. In December, he started taking methadone at a nearby clinic to ease his opioid withdrawal symptoms. Now, he’s determined to find permanent housing and a job.

“It's just not the same down here when you're getting high and when you're not,” said Paul, 38, who asked to be identified by only his first name. “I think I deserve better for myself… It’s not what I want in life; it’s really not.”

A coalition of City Council members who have described themselves as “the Kensington caucus” say they’re working to create a “triage” system for people who are unhoused and living with addiction in the neighborhood. Council members Mike Driscoll (District 6), Quetcy Lozada (District 7), Mark Squilla (District 1), and Jim Harrity, an at-large member who lives in Kensington, make up the group.

“It's an either/or proposition… you're either going to treatment, or you're going to jail,” said Driscoll, who represents a portion of the Kensington and Allegheny avenue intersection. “And that sounds harsh, but we have to start, and we have to be aggressive.”

The caucus does not have all the details about how triaging would work, and Lozada is asking constituents to “be patient.”

“I know that's a lot to ask for a community that has been living in these conditions for a really long time,” she said. “We've said from the beginning that this is not going to be easy, and we were not going to get it right immediately. But we are going to get it right.”

So far, Lozada and Squilla say they have provided Mayor Cherelle Parker’s administration with a list of locations that could serve as “triage centers,” where staff would assess whether people need help addressing a wide range of challenges related to addiction and mental health.

Lozada would not name potential locations because she doesn’t know “where the administration is in that process.”

“Part of the work that we have done as the Kensington caucus is to say ‘here are options’,” Lozada said.

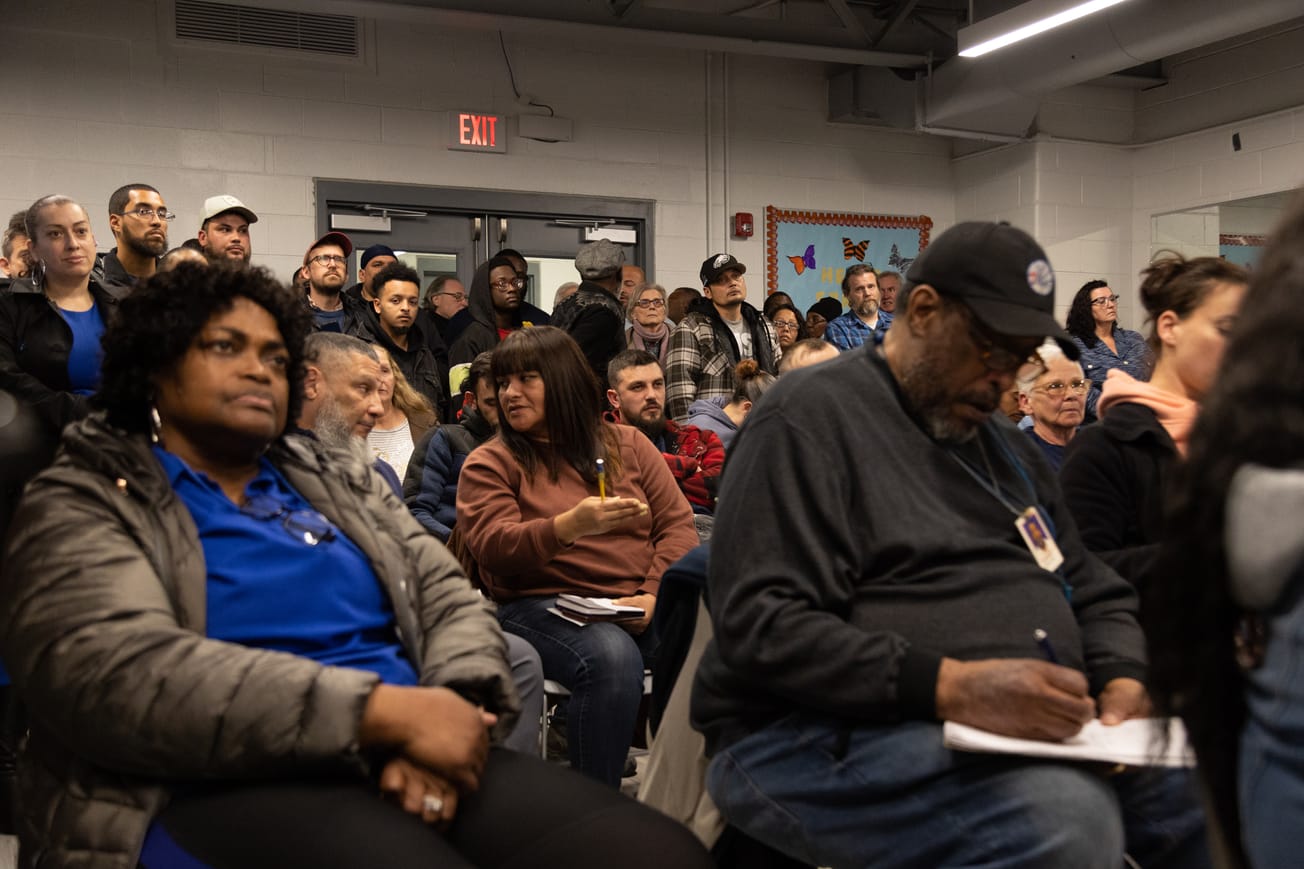

The triage concept emerged nearly a year after City Council voted in favor of Lozada’s resolution to hold public hearings focused on the quality of life in Kensington, the most recent of which was held in July at Conwell Middle School.

It also follows City Council’s nearly unanimous decision to ban “narcotics injection sites” – more commonly known as safe injection sites – in Kensington and every other City Council district except District 3.

The bill to ban safe injection sites and the resolution leading to the quality-of-life hearings were co-sponsored by the Kensington caucus members, among other council members.

For the last 10 years, the area around the Kensington and Allegheny avenue intersection has been split between two council districts. But in 2022, City Council voted on new boundaries that split the area into three, bringing Driscoll into the fold.

“By having this caucus or group of four folks really pushing this agenda, now you're seeing more and more members of council buying into help and support, dedicating their support, going to meetings in those areas, to really try to understand what's happening,” Squilla said.

Noelle Foizen, director of the city’s Opioid Response Unit, said she was “not familiar with [the triage idea] at all based on how the council members are scooping it” but that she is in favor of locating mental health and addiction services in an accessible location.

“If police are transporting them, and that's the only way it gets there, then it can really be anywhere, right?” she said. “If the facility would operate sort of like a drop-in component where people could come and go, it would need to be accessible, maybe via public transit.”

She noted that city leaders should get community input before implementing the plan.

Parker’s administration is not ready to comment on the triage concept, according to spokesperson Joe Grace, but is exploring “all options and funding sources for providing long-term housing, care and treatment for our most vulnerable residents.” Parker’s team plans to release a more specific strategy for Kensington later this spring.

Requests to speak to representatives from the Managing Director’s Office, including the Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual DisAbility Services (DBHIDS), were routed to the Office of the Mayor. The mayor’s office did not make those representatives available for comment in time for publication.

The Philadelphia Police Department also did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

‘It just doesn’t make any sense’

As of mid-January, Kensington caucus members were not clear on how people would get to the “triage centers.”

Councilmember Driscoll suggested police arrest people for crimes, including open-air drug use and prostitution, and then bring them in. Squilla said services would be offered first before criminal justice consequences would be presented.

District Attorney Larry Krasner said his office prosecutes drug possession cases, except for marijuana and buprenorphine, a prescription medication used to treat opioid use disorder that is often purchased illegally on the street.

Most of the possession cases that make it to Krasner’s office also involve more serious crimes, including drug sales, according to spokesperson Jane Roh. Krasner said prosecutors have to dismiss those cases when they can’t secure a conviction because of funding limitations.

“Our office prosecutes, in ways that we consider to be just, every drug possession case we get,” Krasner said. “For years, the Kenney administration has not put enough money into the Philadelphia forensics lab for the DA's office even to get an analysis of what drug it is. And that is absolutely required in order for us to be able to obtain a conviction."

The District Attorney’s office dismissed 42% of the drug possession cases it received in 2023, according to the office’s most recent data. About 21% of cases resulted in a guilty plea, 15% were funneled into a diversion program, and 19% were “withdrawn in the interest of justice.” The rest were exonerated, won on appeals, acquitted, or found not guilty.

Krasner said he doesn’t support an increase in arrests or prosecutions of people who use drugs or people who engage in sex work.

“Our job as prosecutors isn't to beat the crap out of victims, it’s to try to help them,” Krasner said. “It just doesn't make any sense when our time and resources should go to solving unsolved homicides, unsolved shootings, and going after big-time drug dealers.”

According to Krasner, he has tried and failed to meet with Parker since the primary election, adding that he regularly meets with police representatives and councilmembers invested in the Kensington area.

He said he’s heard local leaders bring up the “triage center” concept and believes it could work – but only if it’s a comprehensive model that incorporates trauma services, long-term addiction treatment, and housing.

“What they mean by triage centers remains to be seen,” he said. “Do they mean this kind of simplistic approach where we're going to bring you in and give you one chance to straighten out your life? … Are we going to pretend that giving people one opportunity and then putting them in jail is a solid solution, only to watch them come out and die of a fatal overdose shortly thereafter?”

Squilla and Lozada said they are holding off on releasing details of this plan until newly appointed Deputy Police Commissioner Pedro Rosario has had more time in his post.

“In order for us to operationalize the plan, or for the plan to be created, we needed to figure out who that right person was for the job,” Lozada said. “All of those … logistics of the plan will fall into place, once we give him the opportunity to sit down with his leadership.”

Councilmember-at-large Jim Harrity said in an emailed response that Rosario “must execute a plan to increase arrests for retail theft and other quality of life crimes that affect the business and neighbors of Kensington.”

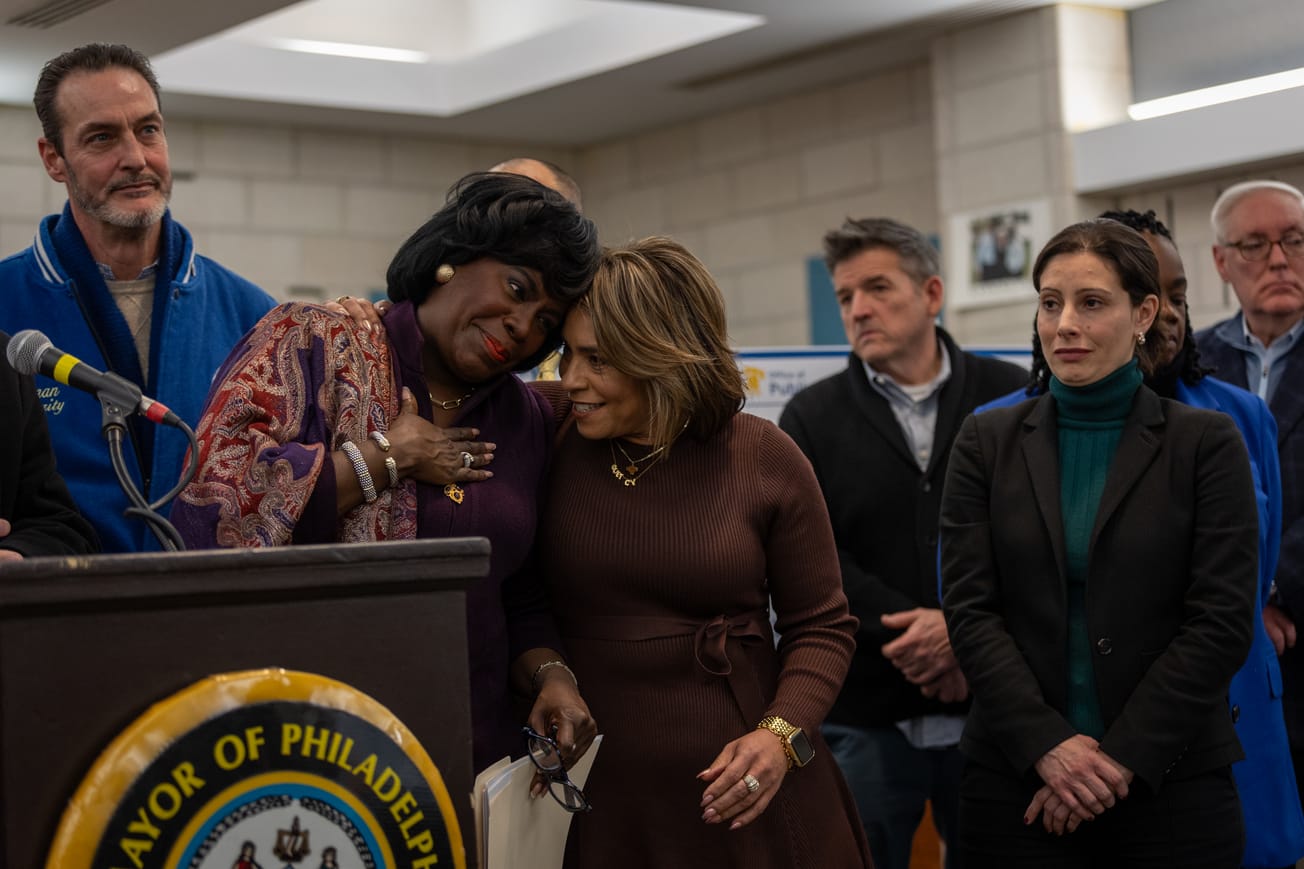

The Parker administration recently appointed Rosario, formerly a 24th district captain, to head up efforts to “permanently shut down open-air drug markets” in Kensington, as stated in Parker’s 100-day action plan. The appointment has drawn positive reception from neighborhood residents and city staff.

“I’ve worked really closely with Deputy Commissioner Rosario in the past, and I’m so hopeful that he’ll have the tools and resources that he needs to try and turn things around for the community that has been severely impacted,” Foizen said.

An influx of police officers to the area could help restore a sense of lawfulness to Kensington and encourage people who use drugs on the streets to do so indoors, said Patrice Rogers, founder and director of Kensington Avenue nonprofit Stop the Risk.

“It’s probably time for somebody to come to protect us,” Rogers said. “And it's not forcing them into recovery. It's, ‘you're breaking the law. Period, point blank,’ … you shouldn't be allowed to openly use in public. But I do believe that we should have safe places for people that don't want to be in recovery to be.”

Higher rates of drug-related incarceration don’t translate to lower rates of drug use or overdose deaths, according to a 2018 Pew Research analysis. And an increased law enforcement presence at various times during the Kenney administration did not have long-lasting quality-of-life results in Kensington.

Arresting people who use drugs won’t solve the problem, said Sarah, 30, whose last name was withheld for privacy reasons. She’s been living between friends’ houses in Kensington since about 2020. She was in recovery for most of her 20’s when she was living elsewhere but has been struggling with addiction since returning to the neighborhood.

“Creating better treatment facilities and making that more accessible to people who are struggling, like people that have Medicaid, and people who aren't able to afford those private, bougie, fancy facilities – that is going to be what's helpful,” Sarah said.

Paul said incarcerating someone who uses drugs won’t stop them from repeating the same patterns once they’re released.

“I did good in prison the whole time, then they threw me back out in Kensington,” Paul said. “You don’t throw a drug addict back down in Kensington... That’s why I’m doing my best to try to get out of here.”

‘We may have to use a 302 system’

Councilmember Squilla suggested the city create a policy similar to Pennsylvania's code 302, which allows police officers to involuntarily commit someone who is “a clear and present danger to themselves or others” to psychiatric evaluation and inpatient treatment for 72 hours.

“We may have to use a 302 system or other systems to be able to say, ‘you know what, you're doing something here that's really hurting yourself and could possibly hurt others – we need to bring you in’,” Squilla said. “But do it in a way where we can triage them to find out what the problems are, look at them and see what care they need, and then hopefully direct them to that care.”

A Pennsylvania Senate bill currently moving through the legislature would make it legal for anyone who overdoses and is transported to an emergency room to be involuntarily admitted into inpatient detox treatment for 20 days, with the potential for additional mandated treatment after further evaluation, according to the bill text.

But Carla Sofronski, director of the Pennsylvania Harm Reduction Network, said forcing people who use drugs into treatment is not legal or ethical.

“It seems like we’re pulling at straws to fix an epidemic that is extremely complex,” Sofronski said. “This idea that everyone has to go to treatment is absurd. We need clear guidance and protocols for treatment. To force people into systems that have no clue what they’re doing is horrific, and it’s malpractice.”

Speakers at Rosario’s swearing-in did not address concrete plans for treatment and recovery options for people who use drugs in Kensington, and representatives from the health and behavioral health departments did not take the podium.

“[The administration is] guiding this through a law enforcement lens,” Sofronski said. “We are not looking at the best public health policies… The systems and the people on the ground really need to come together and sit at a table to gain a better understanding of the complex issues that they're dealing with.”

Shea Hoffman, a volunteer with Mother of Mercy House, which provides food, clothing, and wound care out of its Allegheny Avenue center, worries the new plan will just force people into a cycle of detox and homelessness.

“It’s a big carousel ride,” said Hoffmann, 32, who has been in recovery for 12 years. “If you're going to offer them treatment, it needs to be longer than a detox.”

His mother, Dianne Hoffmann, runs Mother of Mercy House’s youth and family programs, where she regularly sees people who return from rehab fall back into addiction.

“They come back down here in their pajama pants that they were given. Some of them have a suitcase and now they're dropped off exactly where they were picked up,” she said. “It just doesn't work.”

‘It’s completely voluntary’

The Philadelphia Police Department already offers a second chance to people who commit low-level, nonviolent offenses in the 24th, 39th, and 22nd districts under the police-assisted diversion pilot or PAD, launched in 2017. Through the PAD program, instead of arresting nonviolent offenders, police connect them to social services, including drug treatment.

PAD includes two types of referrals: a “stop referral” for when someone is committing an eligible offense (possession of drugs, retail theft, prostitution), and a “social referral,” which is initiated through officer outreach, walk-ins to the PAD office on F Street and Allegheny Avenue, or recommendations from behavioral health specialists.

Stop referrals begin with a brief intake process completed by PAD staff and an in-depth intake at an affiliated service provider within two days, according to a 2021 University of Pennsylvania study of the program. If someone chooses not to remain engaged with the handoff services, it “does not result in further prosecution,” the Penn study reported.

Councilmembers Lozada and Squilla voiced concern about the need for more data showing whether people who are eligible PAD actually stick with the program and receive services. The mayor’s office did not respond to requests for those numbers in time for publication.

“Not seeing that follow through at the end, not seeing the data that we've been requesting, makes us doubt the program,” Squilla said.

One of the service organizations that partners with PAD is the New Day to Stop Human Trafficking on Kensington Avenue and Mascher Street. Most of the referrals they get are for people who are involved in sex trafficking, sex work, or a domestic violence situation, said Heather LaRocca, New Day’s director.

The organization conducted 98 intakes from PAD from 2021 to 2022, and 22 of those clients returned for services after diversion, according to New Day’s annual report.

“They're brought to us, the police leave, and then we will just basically do an intake and offer services,” LaRocca said. “And we've had pretty good success in folks returning. It’s completely voluntary; nothing’s mandated.”

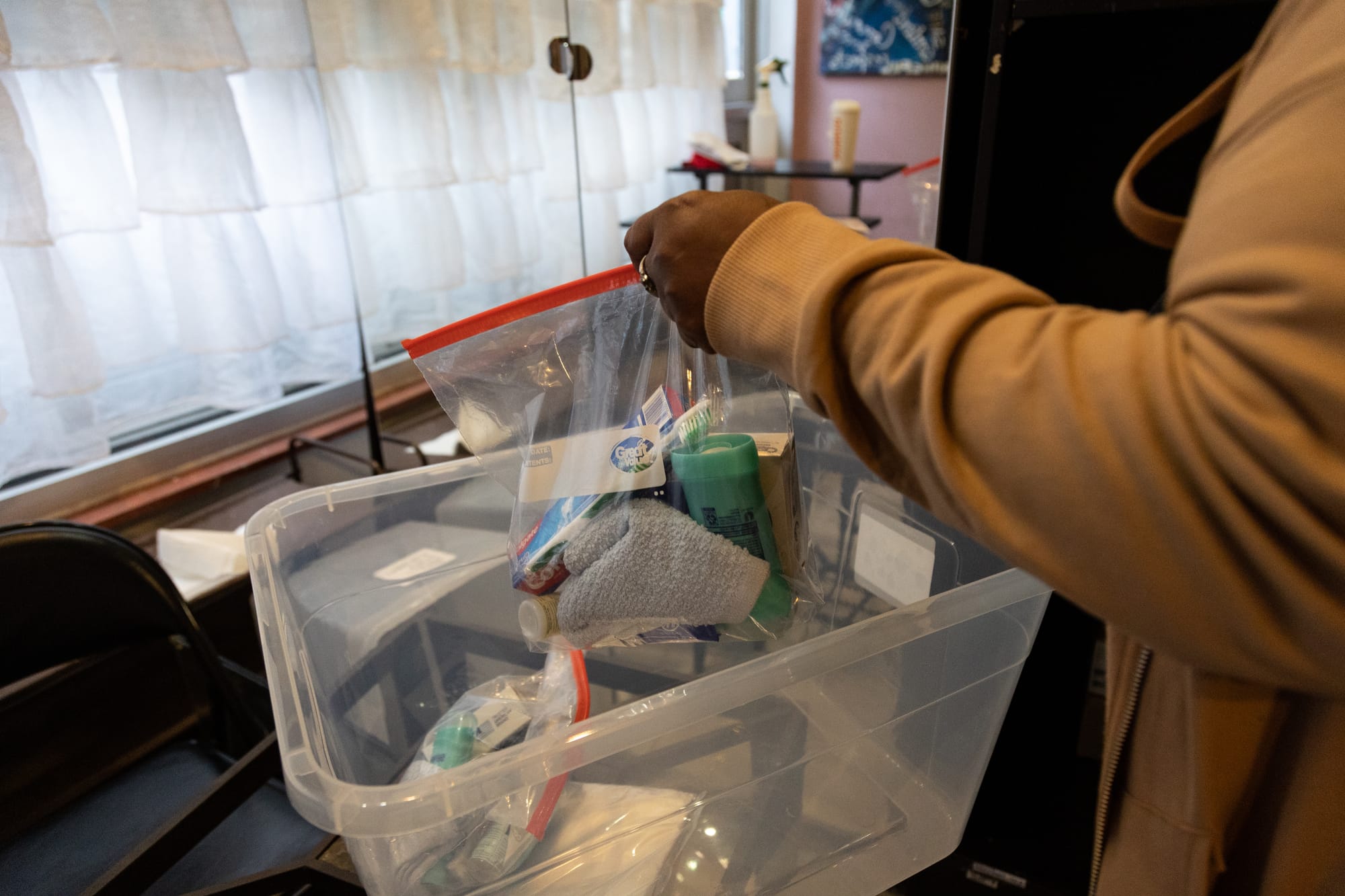

Sofronski said drop-in centers like LaRocca’s are the best place for people to warm up, get basic medical care, and find connections to longer-term help.

“For people to be able to take showers, and do laundry, and engage with people who work in a space with lived experience who can provide compassion, support, and navigation services,” Sofronski said.

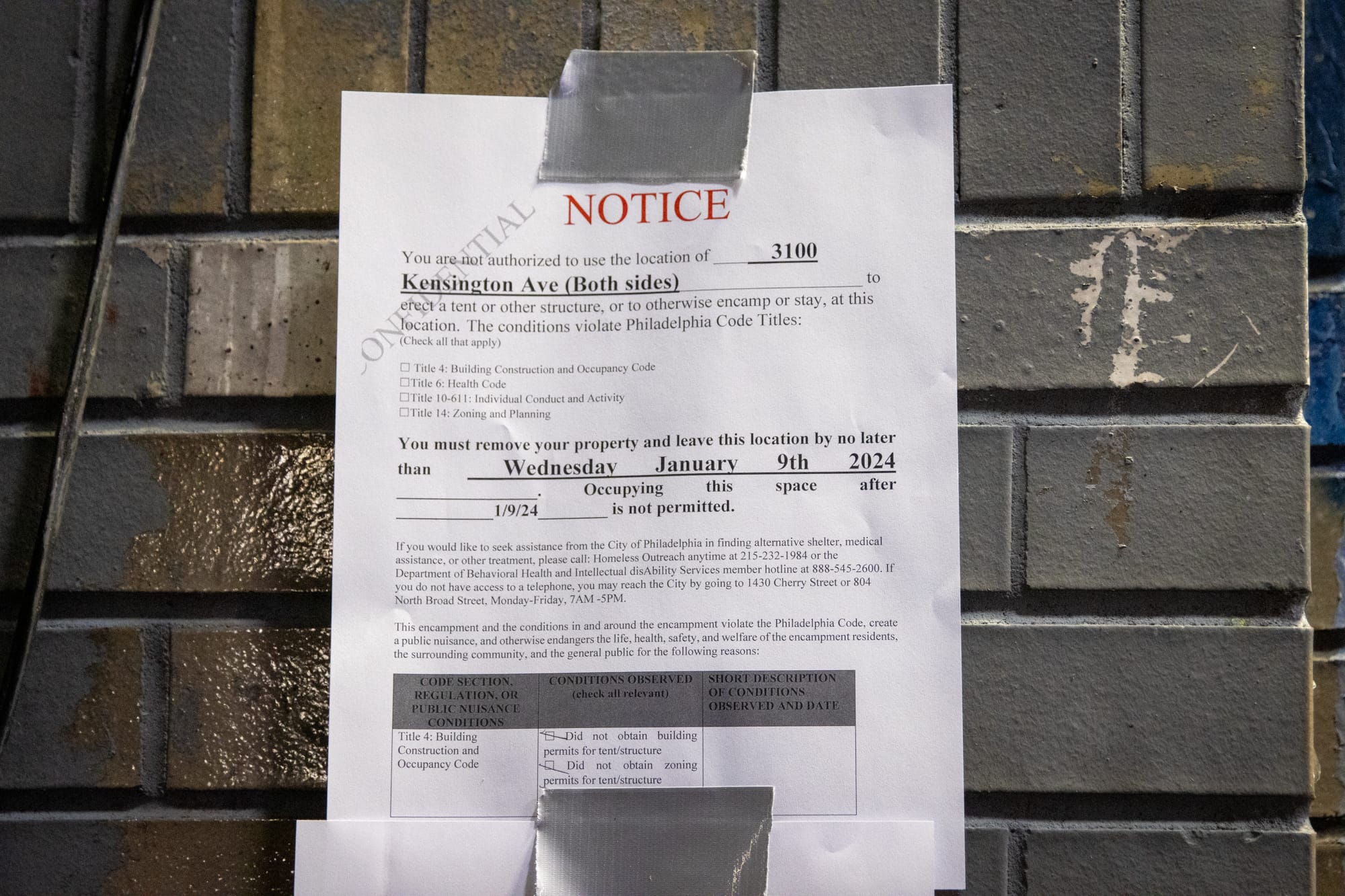

But according to Sofronski, when the police or other city agents sweep the streets and relocate camps, people often lose their identification and other documents that outreach workers spent “hours and hours and hours” helping them acquire. She hopes the Parker administration will give outreach workers a heads up when enforcement actions are coming.

“Letting people know, ‘this is what's going to happen, communicate to them, find a safe place for your belongings, any important paperwork, take it to a safe location, make sure it's locked up, take pictures of it’,” Sofronski said. “Letting people also know their rights … and who for them to contact if their rights have been violated.”

‘Horrific wounds’

In the Behavioral Wellness Center mobile unit on Kensington Avenue, registered nurse Elaina Rodriguez has a laminated chart depicting five stages of wounds that someone using opioids can present with. The photos range from shallow, pink lesions to deep, oozing pockets surrounded by necrotic tissue.

Rodriguez can address a wound in stages one through three. If it’s a four or five, the patient must go to an emergency room.

“We’re not allowed to get those clients with that kind of wound because they need a more in-depth treatment,” Rodriguez said.

Mobile unit staff say wounds have become increasingly severe in the last three years as more people are using xylazine, also known as “tranq.”

In 2021, the drug was present in roughly 90% of samples of Philadelphia’s heroin and fentanyl supply, according to the city’s health department, making it the most common adulterant in the drug supply.

Dr. Jill Bowen, commissioner of the city’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual DisAbility Services, raised the issue as a barrier to treatment at Lozada’s July quality-of-life hearing.

“It’s been the wounds that have blocked people from getting into rehab,” Bowen said. “It’s such horrific wounds that it needs medical care before the rehab unit.”

People who were initially ready to begin detox may change their minds while they’re getting medical care, LaRocca said. Others may choose not to go to the hospital at all.

“People don't want to get the medical treatment because their substance use isn't going to be treated,” said LaRocca, who is trying to add wound care services to New Day’s drop-in center. “They don't want it; they're gonna be horribly sick if they try to go.”

Temple University addiction specialists said they had to create new protocols to address people who come in with complex wounds and are also addicted to drugs. Recovery specialists can help with detox management and also discuss longer-term treatment options.

“Their opioid needs from what they're using on the street is really high to replace, “ said Dr. Daniel del Portal, senior vice president of medical operations and chief clinical officer for Temple. “They'll go into withdrawal unless you replace that with either an opioid agonist like an oxycontin, or buprenorphine or methadone.”

Temple physicians also helped develop the City of Philadelphia’s health department to create a new treatment guideline for xylazine wounds.

“A lot of resources are needed to take care of this group of patients and both medical and addiction complexity that they bring, in terms of how we support that in a sustainable way,” del Portal said.

‘Those beds go every single day’

Once someone’s wounds or other medical needs have been addressed, Temple’s consult team can try to place those ready to enter inpatient treatment in a detox facility.

“If they end up coming in earlier in the day, there's a lot better chance that they will leave linked and transferred to an inpatient rehab bed,” said Dr. Sam Stern, an addiction medicine specialist at Temple who regularly treats people with substance use disorders in the emergency room, at community clinics, and via street medicine. “Earlier in the day is better, because those beds go every single day.”

The city plans to conduct an analysis of all shelter, treatment and recovery beds, according to Grace and Foizen.

“It's challenging to connect folks to services outside of nine to five,” she said. “And so those are sort of the gaps that we've really been focused on … making sure that not only do you have the resources available, but they're at a facility that folks want to go to because they've heard good things about it.”

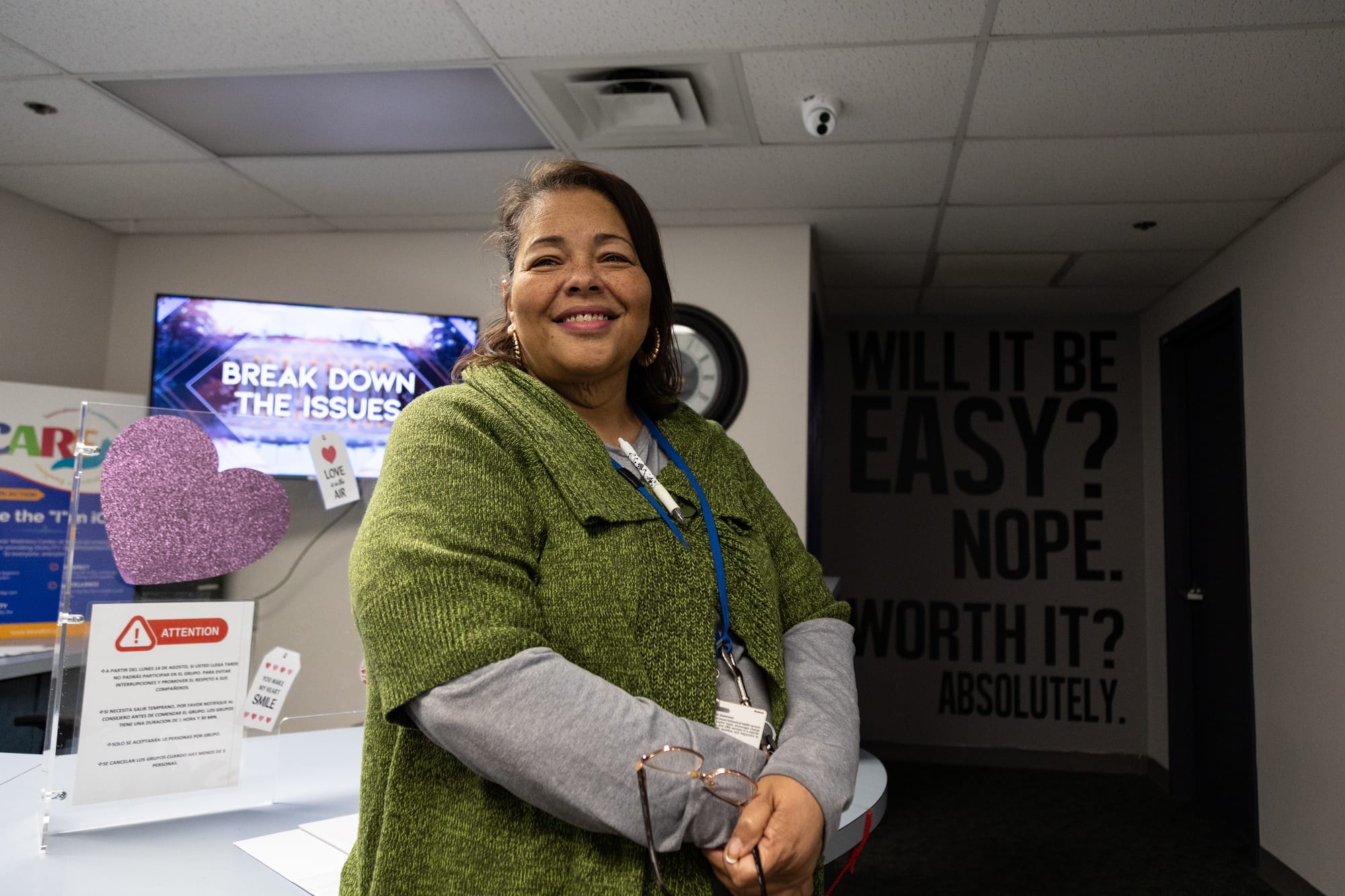

Ruth Rosario, admissions coordinator in the Behavioral Wellness Center’s mobile unit, said her team calls ahead when they send someone to the hospital with a wound so a supervisor knows that the mobile unit is making a treatment plan for them. If the patient has been assessed at the hospital and is ready to enter inpatient treatment, the clinic’s staff try to hold a bed at their main inpatient facility on 8th Street and Girard Avenue.

“So as soon as they come out [of the hospital], if there's an available bed, we'll make sure that the person comes in,” Rosario said. “If there isn't a bed available, [we’ll] actually help out with placing them somewhere else.”

Outreach workers who do this referral work face a lot of challenges, especially those working for small nonprofits that don’t have the time to call multiple facilities.

“We've called places that said we have ‘no, we have no beds’,” said Dianne Hoffmann at Mother of Mercy.

Hoffman suggested the city should create one phone line that can quickly connect people ready for treatment with a place to go.

“You got to get them when you get them, they're not coming back tomorrow,” she said. “If I can call someone and they say ‘yes,’ I can say ‘sit down, I’m gonna get your coffee,’ and I can get an Uber and I can go with them or somebody can – that would work. It would, but we don't have that.”

Health providers are also focused on helping people find housing so they have a place to stay while they’re deciding whether to go to detox or waiting for a treatment bed. It also gives them a place to recover after they’re released. Dr. Stern said even having a safe place to store meds is a crucial part of the solution.

“We get them to the appropriate level of care, everything's looking good, if there's not stable housing associated with folks, then it's going to make the journey so much more difficult,” he said.

Councilmember Lozada said working with treatment providers and understanding the landscape of services in Philadelphia is a critical step in the plan for Kensington.

“Just being able to talk to them, and then talk to our federal and state counterparts to figure out financial resources, as well as physical resources like beds and where those beds are and how those beds are built – those are things that I'm learning about right now,” Lozada said.

She added that she and Squilla have been speaking with the Philadelphia Department of Prisons about drug treatment options there and whether facilities have the capacity to handle an influx of people from Kensington.

“I don't think that people who are living on the streets right now understand that there is a really decent process in place right now that our prison systems are capable of putting them through to get them to a place where they're stabilized,” she said.

For Sarah, who is still unhoused in Kensington, the key to helping people change their lives is creating a range of affordable, accessible recovery options, including harm reduction options, staffed by people who have experience around addiction.

“Not just ‘become abstinent or die,’ like there can't just be one way to recover,” she said. “Making housing more available to those who are still using substances, because it's really freaking hard to recover when you're living on the street. You know, it's really hard to do anything when you don't have any resources.”

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.