Kensington news: Breakfast with Santa, ‘Deck the Walls’ art show and more

Hey there, neighbors. Coming up this week, Santa is picture-ready for free photos at Scanlon Rec Center, local artists are

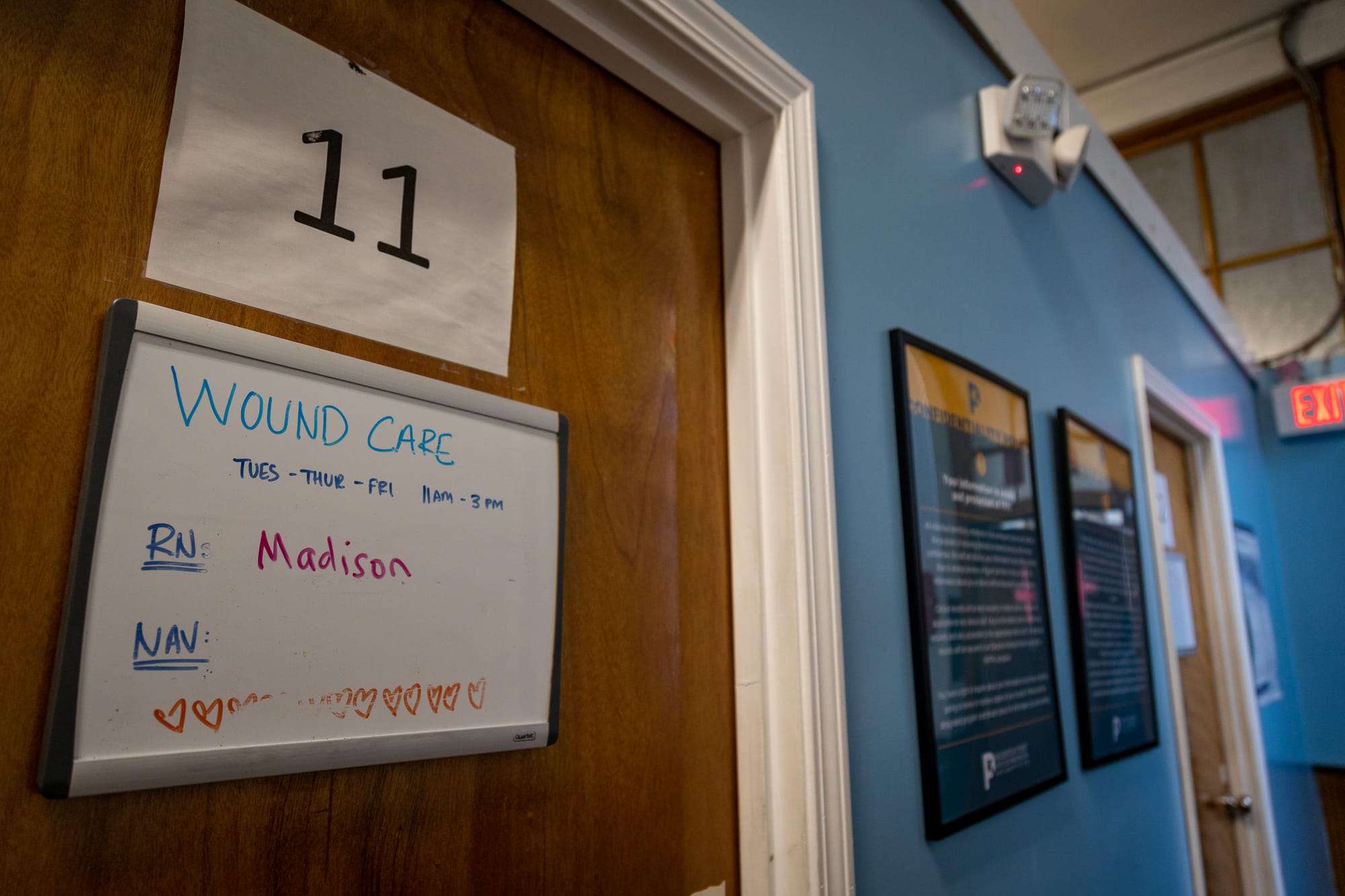

The clinic provides HIV and Hepatitis-C testing and treatment, medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), wound care, STI testing and treatment, and more.

Following multiple public discussions about the future of Prevention Point’s medical services, the Philadelphia Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA) on Wednesday rejected the health services nonprofit’s appeal to function as a group medical clinic at its Kensington Avenue location.

Since October, local medical professionals, recovery specialists, neighbors, and people with lived experience of addiction have testified and filed letters in support of Prevention Point’s medical services. Others, including residents and city council members Quetcy Lozada (7th District), Mike Driscoll (6th District), Mark Squilla (1st District), and Jim Harrity (at-large) have expressed opposition.

Prevention Point has operated its clinic staffed by multiple medical providers without the proper zoning approval since 2015, according to the nonprofit’s attorney, Michael Phillips. The organization was under the impression its landlord had received the approval, when they hadn’t, Phillips said.

It currently has zoning that allows it to host just one medical practitioner at a time.

After the city notified Prevention Point of its need to obtain the permit earlier this year, the organization requested a zoning exception that would allow it to continue providing the same services.

The nonprofit can decide to appeal the ZBA’s Wednesday decision. Prevention Point intends to continue to operate as a group clinic throughout that appeal process, according to Prevention Point spokesperson Cari Feiler Bender.

The clinic provides HIV and Hepatitis-C testing and treatment, medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), wound care, STI testing and treatment, and more.

The first step in the appeal process was a meeting with the local Registered Community Organization, Somerset Neighbors for Better Living (SNBL) in July. The group voted seven to one against Prevention Point’s zoning request and some of its members have continued to resist the organization’s appeal.

In SNBL’s letter to the ZBA, Dominic Chacon, chair of the group’s zoning committee, wrote, “these services come to the area because of the drug users but do not clean up after themselves and also attract more users and drug dealers.” He referenced used needles that collect around the area.

The four council members also wrote a letter to the ZBA. They said that Prevention Point’s medical services don’t belong in a residential area, but in a “medical setting” or “campus.”

Medical professionals from Penn Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University, Drexel University, and other local healthcare and service providers including Courage Medicine, Gaudenzia, Inc., and Project HOME wrote letters in support of Prevention Point’s work. Over 50 residents from the 19134 zip code filed letters, as well as community members from surrounding neighborhoods. Prevention Point also filed petitions signed by 71 “immediate neighbors,” according to documentation provided by the ZBA.

The letters in support of the nonprofit shared a common message — Prevention Point offers lifesaving, low-barrier, trauma-informed care, meets people where they are, and reaches those who often avoid or cannot access hospitals or other medical settings.

Silvana Mazzella, executive director of Prevention Point, said if forced to reduce medical services, care would be delayed — leading to longer lines and wait times. She also said it would likely strain surrounding hospitals.

In her testimony to the ZBA in October, Dr. Monika Van Sant, Prevention Point’s medical director, said limiting access to treatment for HIV or Hepatitis-C would likely increase transmission rates not just amongst substance users but also the broader community.

Patients would be “dying on [neighbors’] doorsteps, quite frankly,” Van Sant said.

Kali Lamb attested to the medical care she received at Prevention Point while both housed and unhoused in the Kensington area. She said she didn’t have the capacity while in active addiction to seek medical care at a hospital, especially without a home or phone.

“I needed somewhere that I could walk up, not feel ashamed of the fact that I had lice, that I hadn't bathed, that I maybe can't keep my appointments,” she said. “I could walk in, receive love and compassion at any time.”

Lamb said she would not be alive without that care.

“I can't count how many times I've overdosed, and my friends had the supplies they needed to keep me alive because they went to Prevention Point.”

Lamb’s testimony was reflected in comments from James Sherman, also in long-term recovery and a clinical research coordinator at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He said while he was unhoused and using drugs in Kensington, Prevention Point treated his wounds without an ID, driver's license, cellphone, mailing address, or insurance.

“I don't think that I would have my arm,” he said.

In July, some Somerset neighbors cited concerns about used needles found around the neighborhood. Marnie Aument-Loughrey, a Kensington “community coordinator” for Mayor Cherelle Parker’s administration, said she did not want Prevention Point nor unhoused people in the community.

Since then, Prevention Point has met with residents and community leaders to hear out their concerns. Prevention Point wanted to “seek common ground,” Bender said.

In a November ZBA meeting, nearby resident Harris Steinberg said Prevention Point shouldn’t be “catering to the drug addicts” and that those living in addiction should get services outside of the neighborhood.

Similar sentiments are driving support for council member Lozada’s bill that could ban mobile health care providers and other mobile services from the 7th district, which covers most of Kensington. The legislation was passed in city council committee last week and will be read by full council for a final vote as early as Dec. 19.

Other resident concerns are related to the fear of people selling drugs targeting individuals seeking services at Prevention Point.

Prevention Point is a “bad neighbor,” said Chacon in a November public comment. “I talk to a lot of my neighbors, most of us avoid going by it as much as possible, sometimes adding up to 30 minutes to our commute,” he said.

Alexis Roth, public health professor at Drexel University who has conducted HIV and overdose related research for over a decade, cited her 2019 research paper which found that out of 360 residents, 90% were in favor of safe consumption sites in the neighborhood. She said there is broad support in the area for addiction treatment at Prevention Point.

She said medical care, in a place where people can sit, stay warm, and drink coffee, “leads to better patient engagement outcomes… rather than sending someone outside of the neighborhood.”

Free accountability journalism, community news, & local resources delivered weekly to your inbox.