For more than 80 years, health experts, scholars, and community advocates have emphasized the dire need for better access to physicians and health centers for Puerto Rican Philadelphians. However, issues with timely doctor visits, preventative health, health insurance, and the lack of doctors from the community in North Philly remain.

Ray Collazo looks outside the window, driving past the tightly packed row houses in Fairhill toward Kensington, his old stomping grounds in the area known as North Philadelphia.

When he was 11, his parents moved to Philadelphia for work, as did many other Puerto Rican laborers and families in the 1940s and ‘50s.

Collazo points to blocks he could never cross, recounting being assaulted by a group of white children the first few weeks in his new neighborhood for crossing North Front Street.

“I could never be over here,” he said. “Here” is the other side of North Front Street, where mostly white, Irish families lived.

The demographic makeup of these neighborhoods is similar 75 years later. Clusters of Latino residents — especially Puerto Rican residents — remain on the west side of Frankford Avenue.

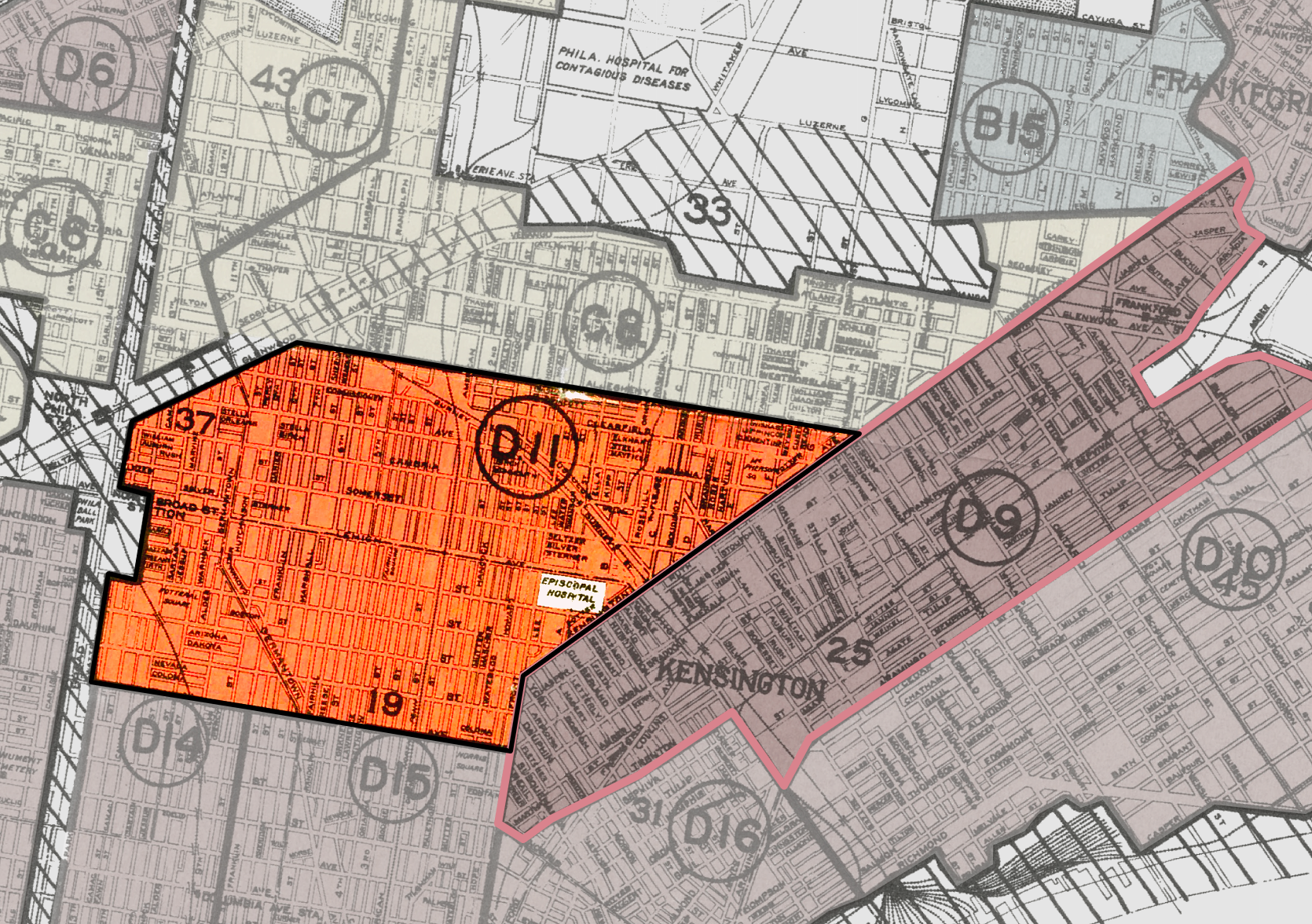

Wealth and housing disparities in communities like Fairhill stem from historic neglect and inconsistent investment. In the 1970s, rapid gentrification displaced Puerto Ricans from Spring Garden, pushing them into economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. This shift deepened unemployment, poverty, and racial discrimination.

Inequities worsened with racially segregated city policies from the 1930s, according to the Center for Urban and Racial Equity. Such redlining policies, shaped by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation’s assessments, flagged neighborhoods with minority populations as “risky,” restricting access to loans and investments.

Over decades, these policies entrenched racial and economic divides, leaving Latinos and Black Philadelphians with homeownership and wealth disparities wider today than they were in the 1960s, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Discrimination, Health, and Care Access

Collazo lived through the residual effects first-hand in his North Philadelphia home.

He is now in his 70s. His eyesight is poor, possibly linked to a diabetes diagnosis. But he’s still social, with many stories to tell.

In the late 1980s, he worked as a mental health counselor for the Asociación de Puertorriqueños en Marcha, a Latino-led nonprofit organization that supports communities with health, human services and economic development.

He remembered young people lining up for mental health help, some of whom struggled with substance use.

“It was horrible,” he said.

Traumatic experiences and a lack of access to care, particularly among low-income Puerto Rican families, were rampant. So were unemployment and drug use, a problem that continues to disproportionately affect the Puerto Rican population.

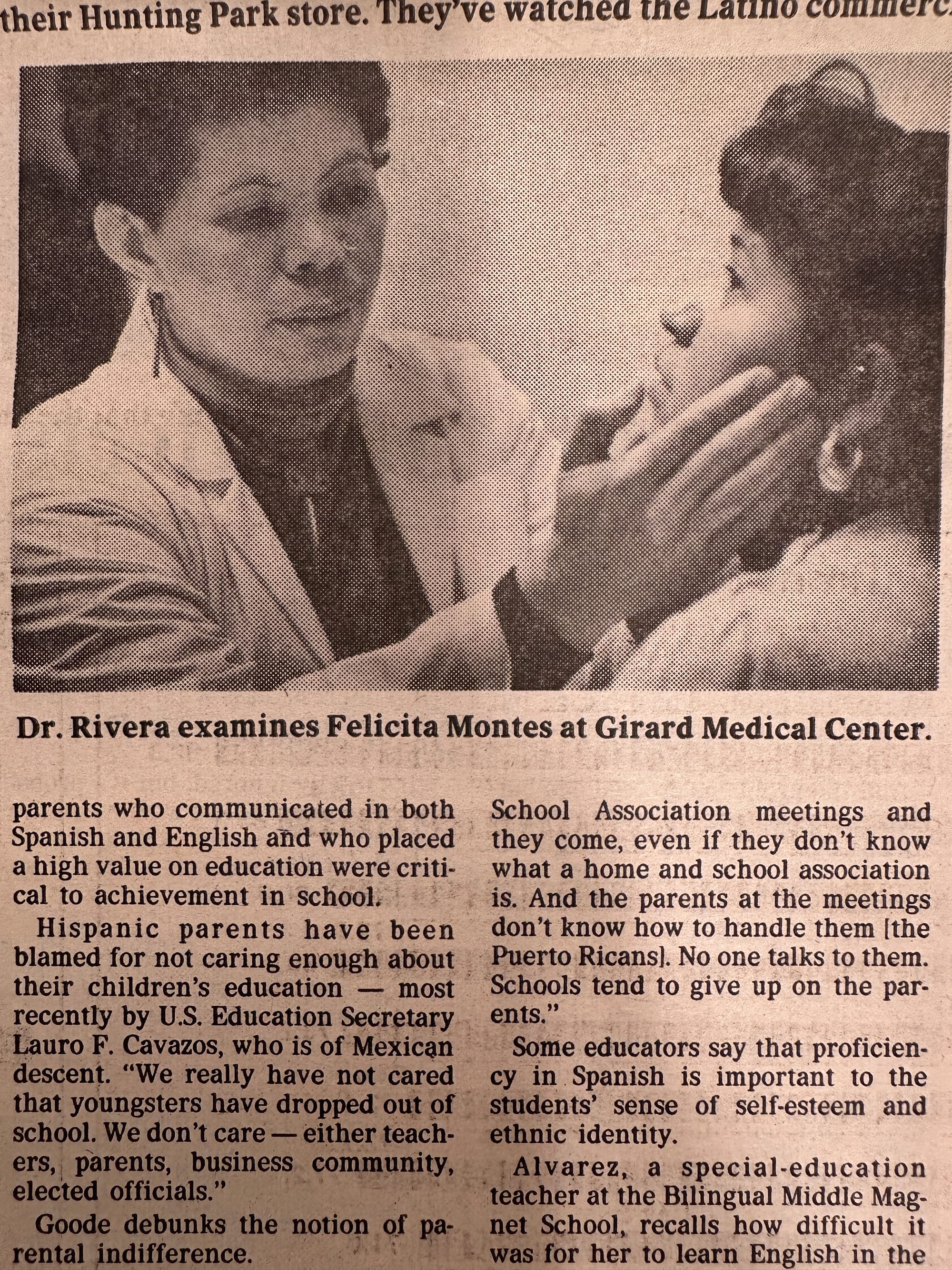

A Philadelphia Inquirer article from 1990, “Puerto Ricans: Adrift in two Worlds,” corroborates what Collazo saw. One year before the article was published, the Commission on Human Relations, a city agency created in 1951 to enforce anti-discrimination laws, raised issues of discrimination and lack of city services within the growing Puerto Rican population.

“The reporters found overwhelming educational and health problems,” the article read.

Dr. Norma Rivera told the Inquirer she had a large caseload of patients with drug and alcohol use in addition to those with diabetes, hypertension and asthma. However, she underscored depression, another severely under-addressed problem.

Decades later, Puerto Rican patients exhibit rates of depression higher than white or other Hispanic populations, according to a 2019 study by psychologist Glorisa Canino, director of the Behavioral Sciences Research Institute in Puerto Rico. The stress of migration or isolation from cultural and social networks exacerbates chronic stressors, the research shows.

Puerto Ricans living in the U.S. self-reported experiencing significantly more anxiety and depression than those on the island, according to the same study.

Discrimination increases the prospect of depressive symptoms, and the risks are significantly higher among the Puerto Rican diaspora, according to a 2022 study in Geriatric Psychiatry.

Philadelphia-based public health scholar, Ana Martínez-Donate, attested to this in her own research.

“We do see a greater impact of things like depression, anxiety and PTSD among Puerto Ricans,” she said.

Martínez-Donate co-authored the study “Provider Perspectives on Latino Immigrants’ Access to Resources for Syndemic Health Issues,” which highlights significant disparities in Latinos’ access to hospitals or health clinics, treatment and diagnosis.

“It is not about the person and what they're doing right or wrong. It's about context. It's about the opportunities that they've had before arriving in Philadelphia and the experiences and traumas that they carry, as well as the support that they find here in the city or the lack thereof,” Martínez-Donate said.

She added: “It's living in neighborhoods that are more prone to crime. It's being more likely to be unemployed or having to pay a greater proportion of your income on rent, it's not having education opportunities because you are not eligible for certain kinds of financial aid. It's lacking health insurance and not being able to see a health provider. It's not speaking English fluently and not having enough providers in the city that are linguistically and culturally competent to serve the community.”

Cost, Language, and Trust Barriers in Health Care

Activists, health advocacy and policy groups have long criticized the U.S. health system for being unaffordable, even with health insurance. High costs make people sicker, causing delays in treatment and unfilled prescriptions, and zeroes out their savings, according to the Commonwealth Fund’s 2023 report.

Medical debt also disproportionately impacts low-income people, Latinos and Black residents, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey. More Latinos in Philadelphia live in poverty than other groups, outlined a Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia analysis.

Community providers with Pennie, the state’s affordable insurance marketplace, and other Latino-serving providers, say Puerto Rican migrants continue to struggle with education and acculturation. However, they rarely disclose their needs to social service agencies, so they are denied support.

Agency workers say many will say they are healthy when they need medical attention. Plus, the Commonwealth’s application portal’s default language is English.

“They're afraid to tell people that they don't know how to read or write,” said Vasti Miranda, who works with a home health agency. “They don't sign up for it. They just let it go.”

Latinos who primarily speak Spanish say their care is better with Latino physicians. Advocates and scholars say clear communication is needed to curb medical mistrust and dissatisfaction in health care.

Political Leadership Tackles Health Care Gaps

City policies on housing and health in the last 35 years have concurrently failed to address the needs, Ray Collazo said. In part, political power is a key piece to opening new health clinics or bolstering staff in communities where health care needs have been overlooked.

Collazo said district leaders, especially those who come from Puerto Rican families, should address these long-standing issues. In the last decade, two women of Puerto Rican descent were elected to political office in the city: 7th District council members María Quiñones-Sánchez (whose term ended in 2022) and Quetcy Lozada.

The predominantly Puerto Rican district has some of the highest poverty and drug use rates in the area, along with chronic health issues. Lozada wants to help, she said.

“My parents are both fluent in English and Spanish, and they still have challenges navigating their health care needs,” she said in a phone call. “We're not a community that trusts, right? It’s hard finding healthcare providers that we can connect with, who we can be honest with or that we understand what they're asking us to do to better improve our health situation.”

North Philadelphia Latinos lack urgent care centers, a limited number of bi-cultural or bilingual physicians and long wait times to see a doctor for those with insurance.

In 2024, Lozada promised to open a new health care center in the Northeast by 2025 to relieve Health Center 10. It is just one step, but Lozada, who supports stronger law enforcement to control the sale and use of drugs in public in Kensington, said she hopes the center helps to bridge the gap.

People were waiting upwards of one year, particularly low-income children and the elderly. Some seniors cited health insurance as a deterrent to seeking care, she recalled.

“Because health insurance is so expensive, older residents would fail to address their health issues. It took a year or more to get an appointment. They couldn’t afford to see a private doctor,” she added.

Social Influences of Health

Blocks of brightly colored homes stand out in Fairhill, some bearing Puerto Rican flags waving by the window.

Puerto Ricans are the largest Hispanic population, comprising around 70% of the Latino/Hispanic Philadelphians, and for years tend to be living in North Philadelphia, where the median income was around $32,000 in 2022.

In Puerto Rico, the average annual income is $25,096 and nearly 40% live in poverty.

The first wave of Puerto Ricans arrived in Philadelphia in the 1800s, recruited as industrial laborers. The count ticked upward in the 1950s, after World War II and as a result of “Operation Bootstrap,” the initiative led by the Government of Puerto Rico to drive the country's industrialization.

Over time, small enclaves were pushed to the more industrial – and more underinvested – areas of the city such as Kensington and Fairhill. Almost half live in poverty.

While the Fairhill neighborhood poverty rate has decreased — from 55% to 41%, according to Census data — ZIP code 19133 is one of the poorest areas in the city. This starkly contrasts one of the wealthiest ZIP codes to the south, Society Hill, which has a 5% poverty rate.

Where people live has an impact on their health, said Martínez-Donate.

“Many of [the health issues are] tied to the living and working conditions of these communities,” she explained.

Collazo’s son, Michael Collazo, remembers growing up in North Philadelphia. Michael, 47, prides himself as a “Philly Puerto Rican.” He grew up in what is colloquially known as “Hispanic North.”

“That community has been sadly that low income forever,” Michael said.

Many were his neighbors.

His late mom, Sonia, spent 25 years helping newcomers apply to social and health services in the 1990s. Many were lower income in neighborhoods with sub-par housing closer to factories, bad health care and poor-quality food.

Families struggled to acclimate to the city’s culture, pace and urban environment. Their homes were usually located in industrialized parts of the city.

Hunting Park, also in North Philadelphia, has the same issue, said Jamile Tellez Lieberman, senior vice president of community engagement, research & health equity at Esperanza, a Latino faith-based nonprofit providing services to the communities in the North.

“The environment itself was not set up necessarily with people in mind,” Tellez Lieberman said. “That means there's not a lot of greening like trees or parks.”

The Society of Behavioral Medicine and the American Heart Association cement the links between poverty and “spatial disparities.” Environmental factors, racism, and poverty contribute to the widening health problems among communities of color and low-income residents.

The only trees Michael remembers were in Hunting Park when he’d hang out with his grandfather munching on bacalaítos (thin cod fritters).

“A lot of the streets and the rowhome blocks, there ain’t no trees. Where [are] you going to put trees?” he said.

The small patch of green is one of the cultural hubs. Tiny and medium-sized Puerto Rican flags flap in the wind to a soundtrack of trumpet-heavy salsa songs blasting on an oversized speaker.

Food Deserts and Health Equity

A quick drive through a gentrified area of the city, Northern Liberties, once a Puerto Rican majority neighborhood, now boasts small organic shops and pricier grocery stores. Fresh fruits and vegetables are neatly arranged and shopped for by a younger, whiter, wealthier demographic.

Closer to the Puerto Rican cultural hub West on 5th Street and Huntingdon Street near Taller Puertorriqueño, corners are earmarked by bodegas, largely immigrant-owned mini-marts or corner stores that sell some fresh produce, but mostly fried food and highly processed snacks.

In Philly, these one-stop shops stock Goya products, including fruit drinks, sazón or seasoning, jarred and canned goods frequently used in Puerto Rican cuisine and made-to-order fried chicken wings. The clerks and cooks are most likely speaking Spanish.

North Philadelphia has limited healthy food options. Additionally, getting to a grocery store or doctor's office is difficult for those without a car or who rely on public transportation. Safety is also a problem.

“When you look for [Puerto] Ricans in poor neighborhoods, they may not have the same access to recreational facilities, to parks, that are safe to use. If you cannot go out and work out, then that's a factor. We have some communities that have food deserts, where people go grocery shopping in a bodega, then you're eating a lot of preservatives,” said Michelle Carrera, a poverty research expert and the executive director of Xiente, a community support organization formerly known as Norris Square Community Alliance.

Food deserts are one of the leading causes of the diseases listed in the public health department's mortality data.

The lack of fresh, healthy foods increases the risk of diabetes, particularly Type 2, and the chronic health conditions listed as causes of death for Puerto Rican residents. It is more challenging to be healthier in regions with food deserts.

“[There’s a false narrative of] residents up here or these families don't care about their health or are not interested in being healthy. That's definitely not true,” said Tellez Lieberman. “People are dealing with a lot and people get tired. Sometimes they have to make tough choices where nobody wins, paying utility bills or buying fruit.”

Preventive care is another key issue.

Retired physician Dr. Carmen Febo-San Miguel has seen health issues in the Puerto Rican diaspora persist and evolve over time. Preventive care is key to curbing health issues later in life.

About 20 years ago, Dr. Febo-San Miguel worked in Philadelphia’s poorest neighborhoods, treating low-income Latinos and Black residents.

The history of the Puerto Rican diaspora’s displacement from neighborhoods is also the story of health decline and medical neglect. Racism and a lack of culturally competent care were pervasive in poverty-stricken areas, Dr. Febo-San Miguel said.

Tellez Lieberman agreed.

“This group of people doesn't have access to these resources that people in a different part of the city have, all the access they could ever want and more. Why is that? There are systems in place that are meant to continue to oppress and harm communities of color, especially those [who] are poor, to keep them unhealthy and disempowered,” she said.

The top 10 causes of death among Philadelphia’s Puerto Ricans can also be linked to a lack of healthcare access.

“This community has been the victim of a number of events that have highlighted the relationship with Puerto Ricans and newcomers,” Dr. Febo-San Miguel added.

This includes police violence, drug overdoses and deaths, and increased crime in high-poverty regions.

After several waves of gentrification, the diaspora was pushed further North, away from quality care centers and central hospitals.

For Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia, access to health care is not separate from other basic necessities. It is inextricably linked.

“I have been involved in multiple fights making the government realize that our communities have been neglected and need to be entered into consideration for funding and resources,” Febo-San Miguel said.

The fights somewhat paid off, she said, but there is still more work to be done.

The Poverty Mirror

Studies show that poverty on the island and in Philadelphia mirror one another, as do health outcomes.

For example, Medicaid data from before Hurricane María in 2017 shows that more Puerto Ricans living in the U.S. self-report their experiences getting to the doctor worse than those on the island.

Generally, Puerto Ricans in the U.S. “report a lack of adequate access to health care, poorer health status, more chronic illnesses, worse psychological distress, and lower life span than other Hispanic and non-Hispanic populations in the U.S,” according to the study “Taking Care of the Puerto Rican Patient.”

Experts connect these to varying “social determinants of health,” such as the act of migrating, environmental pollutants, or a new and complicated health care system. Health complications manifest in different ways in Philadelphia.

“We have high rates of childhood hospitalizations for asthma up here [in North Philadelphia],” Tellez Lieberman said. “That is a manifestation of the breakdowns in the system when it comes to access to health care when you need it.”

Today, the areas where Puerto Ricans live have among the highest rates of chronic conditions, such as obesity and diabetes, according to an Economy League analysis.

Fairhill had the second worst health factor ranking, landing 45th of 46 quartiles, according to a 2019 city report. The analysis considered physical environments, health behaviors, clinical care, and social and economic factors.

Hispanics, in general, self-report their health as “poor or fair,” according to the same Health of the City report.

Puerto Ricans fare worse overall among all Latino groups in the city.

A Drexel University report from 2020 identified areas with a high concentration of people living with “high social vulnerability.” North Philadelphia lights up in every study.

“Latinos in Philadelphia are 2.3 times more likely to not have a primary care provider, and 62% more likely to forgo care due to costs, as compared to [non-Hispanic] whites,” the study reported.

Death rates among Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia are higher, epidemiologists with the city’s public health department told the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (CPI).

However, advocates who work in the communities say these data don’t show the root causes.

“The data can show you something, but the data isn’t in the street, it isn’t talking to people every day,” said Charito Morales, a nurse and community advocate.

Despite her outreach, she said people with health conditions do not prioritize their health. Prescriptions go unfilled and appointments are forgotten.

These behaviors might be symptomatic of generational trauma.

“They are in many ways very similar to other Latino immigrants, except they have U.S. citizenship, but they still face many of the same barriers to good health that their immigrant counterparts face. Language barriers discrimination, poverty and lack of knowledge and awareness about resources and where to go for help,” Martínez-Donate said.

Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican doctors

A new generation of Puerto Rican physicians in Philadelphia is now grappling with their own adjustments.

If it were possible, Dr. Natalia Ortiz said she would have finished medical school in Philadelphia and practiced psychiatry in her home, Puerto Rico.

“My goal was to train and then go back to serve my country,” Ortiz said. “But it was difficult … Even though there is a lot of need to take care of patients who have mental health problems and severe ones, the opportunity to work there … There's a lot of barriers to work.”

Ortiz is among the thousands of Puerto Rican physicians who opted to work in the States. The longstanding economic crisis on the island, combined with privatized health care and issues with insurance reimbursements, made it difficult for physicians like Ortiz to practice there.

For years, health problems on the island have been exacerbated by the climate crises, such as hurricanes Irma and María in 2017. For instance, half of the federally qualified health centers that provide care in underserved areas shuttered post-hurricane devastation, weakening an already fragile health care system that served many people below the poverty line and the elderly.

Ortiz recalled conversations with her friends and colleagues in the medical field, who shared that many patients on the island wait upwards to six months to see a doctor. It gets worse if a patient needs to see a specialist. The hopes of skipping barriers and delays to care prompted many to move to the U.S.

Many migrants from the island seek better medical care and attention, as well as better economic mobility. But for those who arrive in Philadelphia, health care problems manifest differently. Insurance options, such as Medicare Advantage, in Puerto Rico advertise to bundle Medicare A and B to help cover inpatient and outpatient costs. But when Puerto Ricans move to the U.S., they must re-enroll, Ortiz said.

“When they move here, they don't have the same opportunities,” Dr. Ortiz explained. “So, there is a gap in treatment.”

She listed the causes: unemployment, education and language barriers, even among Spanish speakers.

‘A Hard Time’

The city’s public health data coupled with findings of 34-year-old university surveys and 50-year-old news articles illuminates systemic failure and historical neglect.

In the 1960s and 1970s, activists such as the Puerto Rican community group the Young Lords Organization and the Medical Committee for Human Rights pushed to fix that.

Since the first Puerto Rican migrants moved to the city, grassroots leaders created what communities most needed: education, political and economic leadership, and health care. Groups such as Concilio and Asociación de Puertorriqueños en Marcha worked to end inequities.

The Medical Committee heavily criticized the American Medical Association, which — along with pharmaceutical companies and private health insurance companies — had successfully lobbied against universal coverage plans. This hurt the working poor, the Medical Committee for Human Rights said.

Poor health care was particularly pronounced in the Puerto Rican diaspora, said a 1990 study by the Institute for Public Policy Studies at Temple University.

“Puerto Ricans have a hard time in Philadelphia,” the study read. “Compared to Blacks, Whites, and other Hispanics, they have lower incomes, higher unemployment, and worse housing conditions. Their health problems are serious.”

Philadelphia’s health care system and private health insurance marketplace favored those with money, scholars said.

“The picture that develops is one of the conditions placing the Puerto Rican community of Philadelphia under high-health risk,” Temple’s study reported.

Similar issues plague the diaspora today.

Breaking down poverty in ‘Hispanic North’

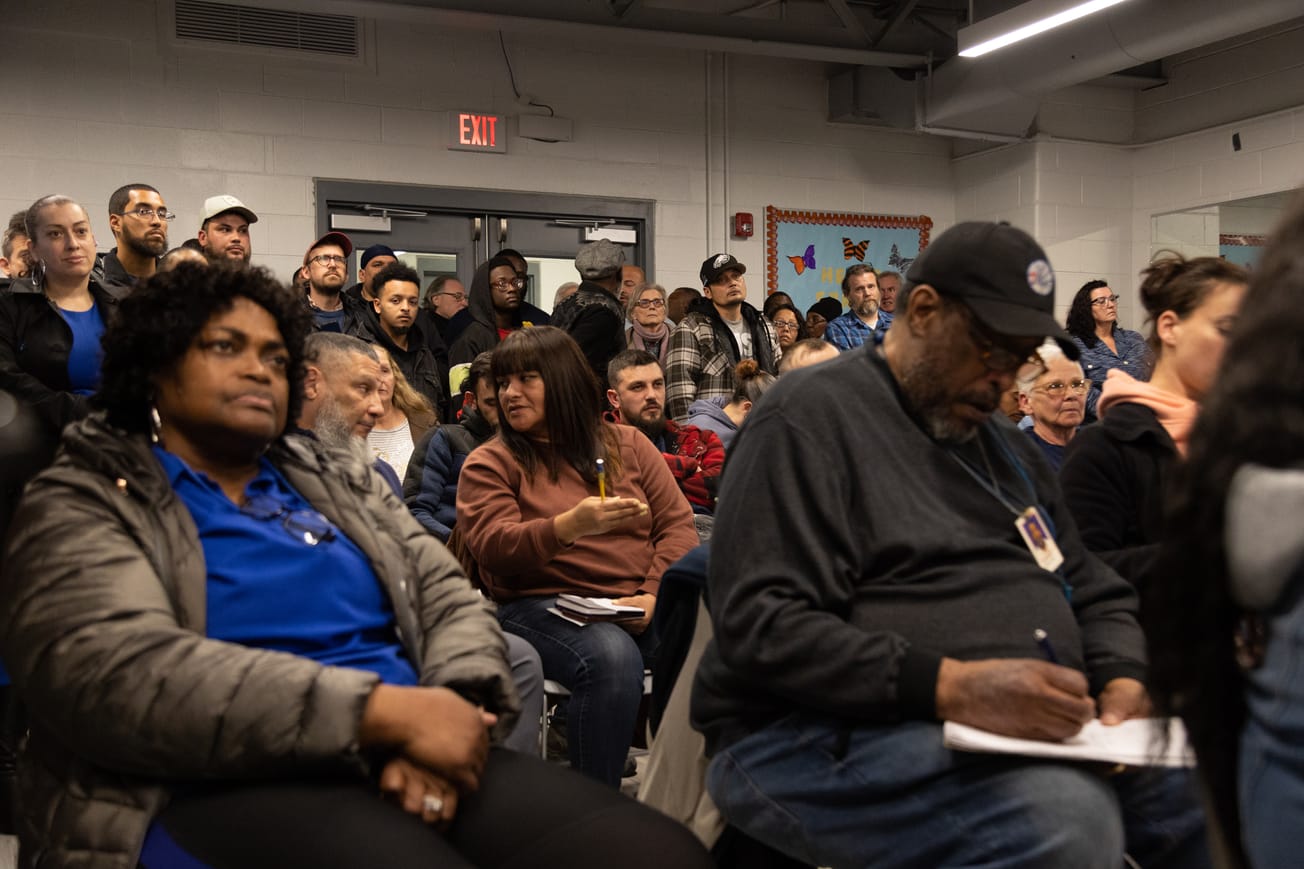

Local activists with Philly Boricuas, including Michael Collazo, routinely press city leaders to step up and invest in the diaspora. Organizers told reporters in 2020 that Puerto Rican Philadelphians were “largely abandoned” by the local government.

Key issues continue to worsen, and they want something to change.

Philly Boricuas is part of a recent wave of grassroots movements. One of the co-founders, Adrián Rivera-Reyes, summed up local health access issues to the issue plaguing Puerto Ricans on the island.

“The poverty level. The people that live in poverty are the working class, the working poor,” Rivera-Reyes said. “They don't have access to these services, or at least not so easily.

“When people are trying to survive day-to-day and they're worried about what to eat next and the bills, it's really hard to be able to take time to go to the healthcare centers.”

Mapa-imagen: Locations of Capital investments

The former city council candidate is also a scientist. He moved to Philadelphia to earn his PhD in cancer biology and stayed in the city as a vocal advocate. He saw the disparities first-hand while canvassing.

“It is striking. Two houses down, you can tell the quality of the house in which people live,” he said. “It all comes back to poverty, disenfranchisement, disinvestment in the community, or lack of investment in the community.”

A Pew analysis of the city’s capital investment commitments from 2011-2022, shows the least financial backing in Census tracts with lower-income people. The top priorities in the city’s 2025 budget are to reduce historical inequities and to invest in key issues such as health care centers.

“The way that we allocate resources is unjust, and it perpetuates these kinds of inequities that we see,” Tellez Lieberman said.

Wide disparities exist in the investments per capita.

The CPI reached out to the Department of Public Health for comment. They were unavailable to comment; however, they said in an email that capital investments are “complex.”

“Generally, the tracts that received larger shares of investment over the period studied had higher median household incomes and higher percentages of White residents,” Pew’s analysis stated.

The city's funding share for social services and safety initiatives was nearly 11% lower in Census tracts with the lowest median incomes. The largest investments, totaling over $30 million, are concentrated in Center City, while investments of less than $2 million are primarily located in North Philadelphia.

Areas like Fairhill.

Studies show that communities in the Puerto Rican diaspora have long suffered from chronic health issues that can be curbed with proper, targeted health education as well as improved access to and funding for quality health care.

‘Cross-cutting’ health disparities, cross-cutting solutions

Although key health activist groups of the 1970s, like the Medical Committee for Human Rights, have since dissipated, they served as models for new advocates such as the Physicians for a National Health Program. In Philadelphia, Drexel University’s Latino Health Collective is another local example.

The group forms CRiSOL Contigo, which in Spanish stands for Resilient and Sustainable Communities Organized by Leaders. The project was founded to address one of the biggest issues in accessing health insurance and care: the language barrier.

The collective emerged at the height of the pandemic. It connects local public health experts, the city’s public health department, and pre-existing Latino-serving organizations to better identify community needs, particularly Spanish-speaking Philadelphians.

In Philadelphia, most Latino-led health nonprofits are centralized in North Philadelphia, but their reach is limited or fragmented.

“What we call ‘syndemics’ is like interrelated epidemics that we treat separately, and we often think of them separately … They’re inseparable and we need more integrated, coordinated services,” Martínez-Donate explained.

By building networks among researchers, community health care workers and physicians working in local hospitals, the collective hopes to address the systemic barriers.

Martínez-Donate and the network of public health scholars pinpointed the most prominent health care gaps, such as persistent mental health problems exacerbated by migration trauma and the COVID-19 pandemic.

“When you find issues that are cross-cutting, that makes it even easier to try and develop initiatives because you know that they can benefit even greater numbers of individuals,” Martínez-Donate said.

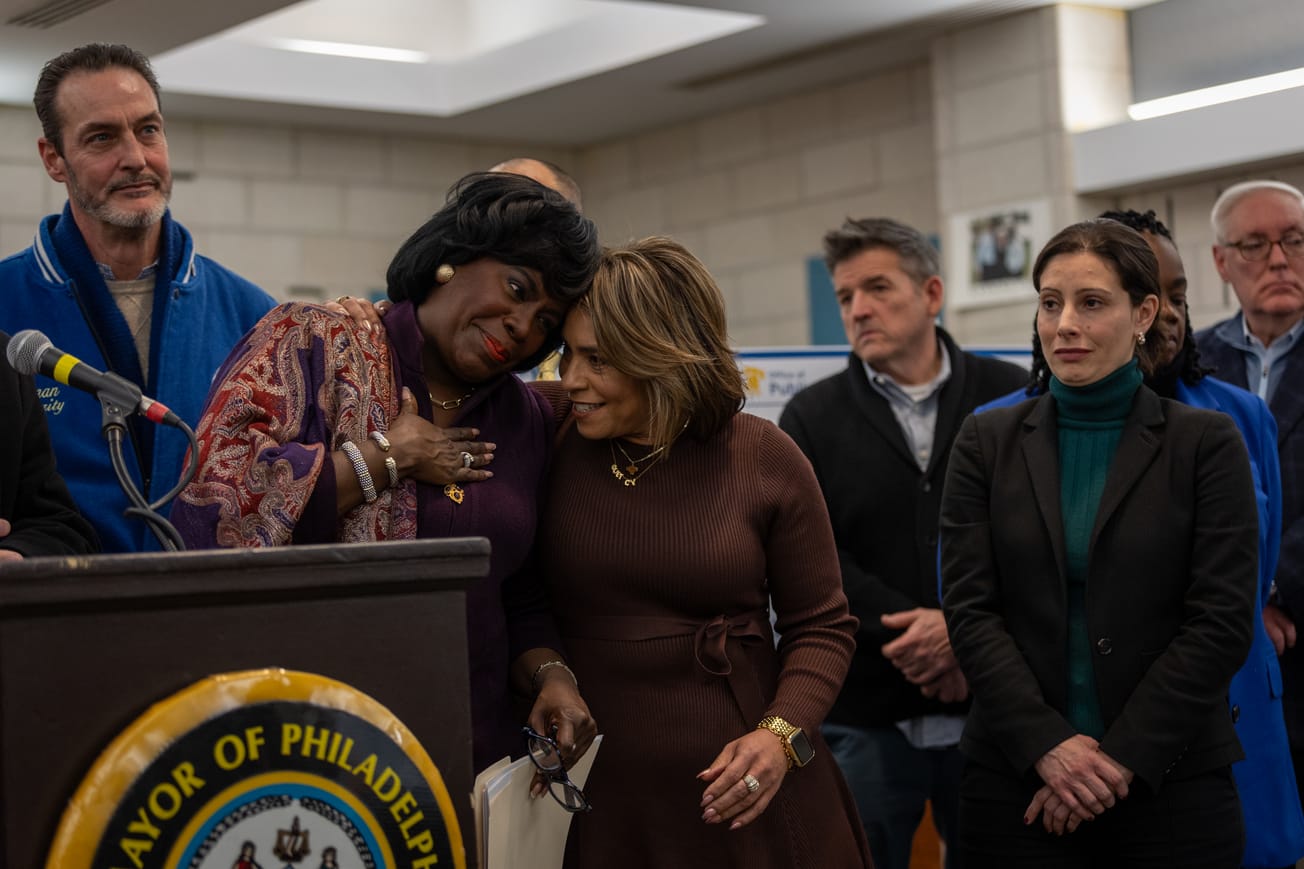

In the coalition's early days, she worked with former health commissioner Cheryl Bettigole to formulate ongoing reports about Latino health needs. Although Bettigole recently stepped down, that provided a roadmap for future collaborative efforts.

“We're hopeful that with the new health commissioner [Palak Raval-Nelson], she will continue prioritizing the health of the minority communities that need more attention,” she said.

This story was made possible by a grant from CPI’s Instituto de Formación Periodística

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.