Since COVID-19 hit Philadelphia last March, homeless service providers have faced shelter outbreaks, staff shortages, emotional exhaustion, and, at times, the pressure to solve a complex crisis with no simple solution. Now, some are scrambling to put together a vaccination plan for their clients — with little support from the city’s Department of Public Health.

“There’s never a good solution for people that are vulnerable, and sick, and are living in a shelter with COVID because it doesn’t ever feel safe where they’re at,” said Dr. Ivel Morales, the clinic medical director at Project HOME’s Hub of Hope, a daytime respite for people experiencing homelessness in the city.

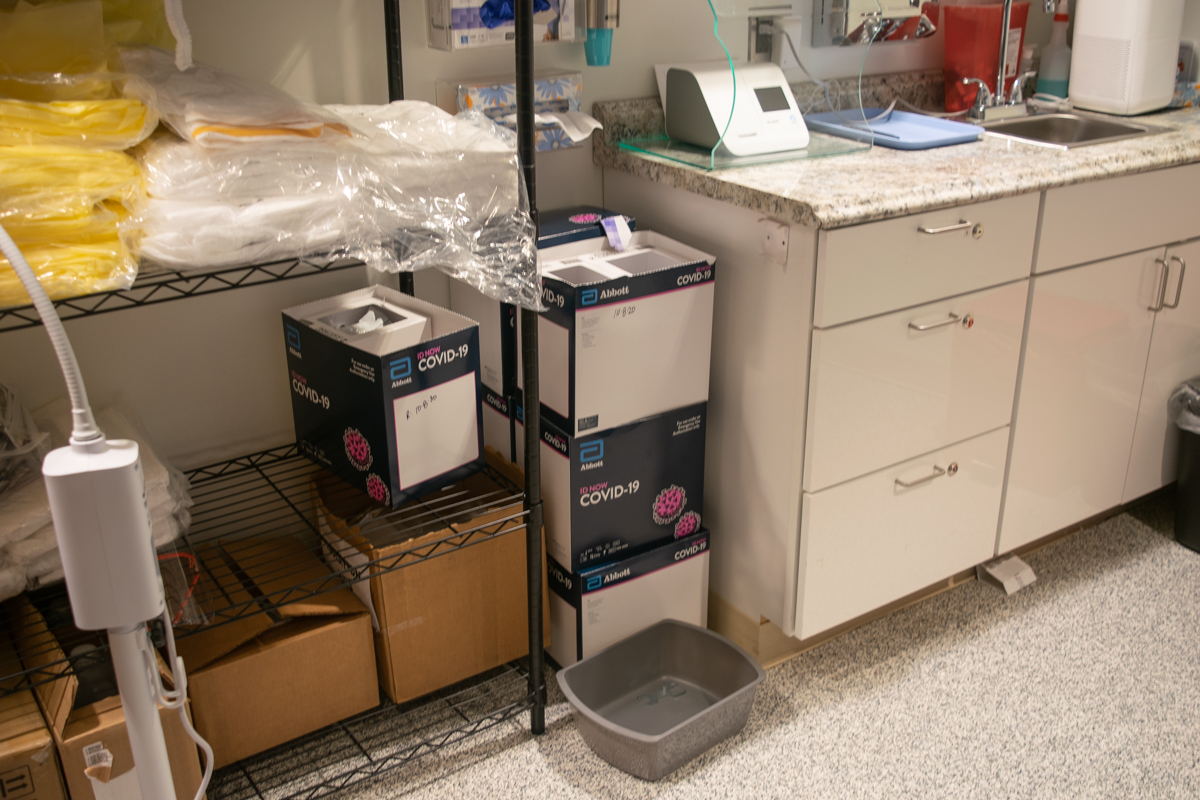

Like other homeless service providers, the Hub began screening and testing guests for COVID-19 in late March. Since then, they say they’ve been doing their best to keep the crisis under control. On Thursday, the health department told the Hub that they could start vaccinating some patients with leftover vaccines from the Stephen Klein Wellness Center, a Project HOME site.

Whether or not the Hub can get a vaccination clinic running by that time depends on securing volunteers and the vaccine supplies, Morales said. As of Friday, the vaccines were still sitting at Stephen Klein Wellness Center.

When people experiencing homelessness get vaccinated depends on a variety of factors

Since January, people living in congregate settings like recovery houses and shelters have been classified as “1B” priority under the city’s vaccination plan. The “1B” group became eligible for vaccination on Monday.

This change was due to an excess of vaccines from the “1A” batch designated for health care workers, according to city officials. Homelessness service providers like the Hub were previously unable to begin vaccinating on Monday due to a lack of clear communication and supplies.

The news is less impactful for providers that are not equipped to offer on-site vaccinations, like Kensington’s Pathways to Housing. Pathways plans to send their participants to partner organizations like Project HOME for vaccinations, according to Director of Nursing Kate Gleason-Bachman.

“There’s nothing that’s quite concrete yet,” Gleason-Bachman said. “[There are] a bunch of things that are kind of getting off the ground, or getting started, or coming soon, but nothing that’s a solid plan.”

Similarly, Prevention Point Philadelphia hopes to receive vaccines for their participants and Kensington community members, but, as of Thursday, the nonprofit organization did not have enough concrete information to provide any further comments, spokesperson Cari Feiler Bender wrote in an email to Kensington Voice.

During an interview with Kensington Voice on Jan. 21, Deputy Health Commissioner Caroline Johnson said that if the city continues at its current pace, it won’t be able to designate new shipments of vaccines to people experiencing homelessness for at least a month. Much of this is due to shipment delays from the federal government which, if resolved, could expedite the process, she added.

For the Hub, assembling a plan to efficiently distribute vaccines will be challenging. Even with the newly allocated supply, Morales said she is unsure if she can set up a full clinic by next week. At the most, she expects to run two vaccination clinics later in the week, she said.

This lack of preparation highlights a conflict that Morales said her team has experienced throughout the pandemic from the city.

“Everything with the pandemic has been reactive, more than proactive,” Morales said. “…Many times it’s felt like: ‘We knew this, why are we behind?’”

As Morales and her team work to set up a vaccination clinic, unique characteristics associated with the vaccines will greatly influence how they’ll provide them.

Vaccine requirements complicate a typical, outreach-based approach

The COVID-19 vaccines’ storage and administration requirements complicate the traditional outreach methods most homeless service providers use. For starters, the Moderna vaccine comes packaged in a ten-dose vial. A vaccinator uses a syringe to extract liquid from the vial to inject it into a patient’s arm. Once the vial is punctured, the vaccinator must use all ten doses within six hours or discard the excess, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

According to Johnson, this means that if the city can set up a daytime vaccination site at a shelter, they will still need to store the vaccine at an official health department site overnight. Meanwhile, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, which must be kept in a special freezer, is not an option for this population at all.

“There’s a big drain on that particular vaccine right now,” Johnson said of the Moderna vaccine, which makes up half of the city’s supply of vaccines. “…We will not be sending vaccines to sit in some refrigerator out at a shelter because it has to be so tightly controlled.”

Monica McCurdy, the vice president of health care services for Project HOME, said she feels the pressure to use all ten doses before the end of each day. Project HOME started vaccinating their health care workers on Jan. 8 and have since begun vaccinating their shelter workers.

“We have to do multiples of 10, so we either want 30 and stop there, or we want 40,” McCurdy said. “But if we get 32, then I’ll be sweating bullets all day trying to find eight more people, because I don’t want to waste eight vaccines.”

Morales is also nervous about wasting her supply. Despite working with patients every day, Morales said she does not have a clear idea of how many people will be willing to receive the vaccine. Some hesitation stems from historical medical mistreatment and trauma, she added, but from those she’s talked to so far, the responses are mixed.

In order to reach the highest number of people, Morales said she imagines a creative street outreach approach — like driving a van full of vaccines around the city and offering them to people panhandling or sitting on the street. This is more of a fantasy than reality, she added, as the health department requires vaccines to be distributed out at the same place they are given.

“That’s another regulation that we have to follow, that we have to give the vaccine here in this space,” Morales said. “That kind of feels like little rules that don’t work well in our environment.”

Adjustments will be needed when planning vaccinations for people in Kensington who experience street homelessness and do not stay in shelters, according to the city’s Office of Homeless Services (OHS).

“As the health crisis deepens, we are aware that the vaccination process for Philadelphians experiencing homelessness in Kensington will require a tailored approach,” Liz Hersh, OHS director, wrote in an email to Kensington Voice. “For example, as single dose vaccines become available, the transient population of people experiencing homelessness would benefit greatly.”

The Office of Homeless Services does not hold power over the vaccine distribution and administration process, as that falls under the health department, but OHS is involved in planning and strategizing, Hersh added. Notably, the two departments formed a Provider Vaccination Workgroup to discuss efficient vaccine distribution for people experiencing homelessness and homeless service workers.

Reassurance, reminders, record keeping, and dealing with discomfort

Many people experiencing homelessness do not have reliable phone or internet service, which means they may be unable to access the city’s online vaccine interest form, a place where residents can express interest in getting the vaccines.

Providers like McCurdy and Morales predict that they will need to have a lot of one-on-one conversations with patients to alert them of appointments, follow-ups for the second vaccine, and to combat misinformation.

Morales said her team is considering incentives like $5 Dunkin Donuts gift cards to increase turnout. They recently used this tactic to encourage patients to get flu shots.

“This is something like a small gesture,” Morales said. “You don’t want to make it feel like you’re paying people to do something they don’t want to do, but it’s more for the inconvenience part.”

Incentives may be particularly useful after the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, she added, which has been shown to produce side effects, like a fever and body aches, according to the CDC. These side effects are common, though not experienced by everyone, and should go away in a few days. From Johnson’s experience, people tend to report discomfort after the second dose of the vaccine, but not the first dose, she said.

However, people experiencing homelessness, who often lack a personal living space, bed, or over-the-counter pain meds, may have fewer remedies to soothe their discomfort. To best meet patients’ needs, Morales said it is important to be transparent about the discomfort people may experience — and perhaps offer a care-package of tylenol, too.

Johnson said that offering care-packages would be reasonable, and it is something the health department will consider when talking to providers.

In addition, providers will be giving patients “vaccination cards,” issued by the CDC to remind patients to return for their second dose. The card includes a patient’s name, date of birth, and the type of vaccine they were administered. Providers can also use these cards to write down when a patient is required to come back for a second dose, Johnson said. For the Moderna vaccine, that’s 28 days after the first dose.

Having an outside provider bring vaccines to a shelter, and then return in 28 days, would be ideal, Johnson said.

Gleason-Bachman, from Pathways to Housing, said the high-risk status of people experiencing homelessness should be a reason to speed up the vaccination process — not a barrier to access.

“Folks experiencing homelessness in Kensington are very high risk,” Gleason-Bachman said. “They need to be vaccinated, and their homeless status should not impact their ability to access the vaccine.”

Gleason-Bachman hopes non-profit organizations in Kensington can work together with the city to help get people vaccinated as quickly as possible, she added.

Once a vaccination plan is in place, herd immunity could be monumental for the homeless population, as close living quarters and insufficient city-run COVID-19 isolation space make social distancing and containment measures difficult.

“It’s refreshing to be talking about vaccines because it does feel like it might be the light at the end of the tunnel,” Morales said. “When I’m having the conversation about vaccinating, and doing it effectively, and doing it fast, there’s a sense of urgency — but there’s also a sense of hope.”

Kensington Voice is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on economic mobility. Read more at brokeinphilly.org or follow on Twitter at @BrokeInPhilly.