Mike Divergigelis didn’t get to hear his brother’s name read aloud at a memorial service for people lost to overdose Thursday.

Divergigelis was volunteering for the annual event. He and several others set up tables at McPherson Square Park to give out Narcan and clean clothes.

But around 5:45 p.m., Philadelphia Police Department officers ordered them to move their tables from their setup near McPherson Square Library down to the street, according to Divergielis and other organizers.

“Within 10 or 15 minutes there were 17-20 police in a big circle around all of us,” he said. “They were pulling up on bikes and kind of popping up out of nowhere. It was a little intimidating.”

The officers told volunteers they couldn’t hand things out at the park, he said. So they moved.

“I didn’t see any of the name readings or anything because I’m down there,” he said. “I missed all of that. My brother’s name was on that, my friend’s name was on that.”

Deputy Police Commissioner Pedro Rosario said he did not know the specifics of how or why the officers approached the event. He said any “vending or distribution of material items in the park proper” requires a permit from the Parks and Recreation Department.

“If [officers] see something formalized inside the park, they’re instructed to challenge, to investigate if they have the proper permit,” he said.

The Parks and Recreation Department website includes permit instructions for events of fewer than 500 people. There is no information listed about resource distribution.

Rosario said he was under the impression that Parks and Recreation doesn’t often approve permits for McPherson Square Park because it’s a “more challenging” area.

The City of Philadelphia did not respond to requests for comment on this policy in time for publication.

Roz Pichardo, director of a Kensington organization called Operation Save Our City who helped organize the march, said she did not have a permit for the event. She said she’s never had one in the six years the march has been happening, and it’s never been a problem.

“We called the 24th and 25th to let them know,” she said. “The walk happens annually. They know this.”

Pichardo said she had a friendly interaction with multiple police officers when she first started setting up tables at McPherson around 4:30 p.m.

About an hour later she went up to Huntingdon Station for the start of the memorial walk, which ends at the park. It was during that time that police asked volunteers to move.

“When I arrived, they had already dismantled our tables,” she said. “This is us honoring people we’ve lost. This isn’t about policy. Why are they doing this at this time?”

Healing and hope

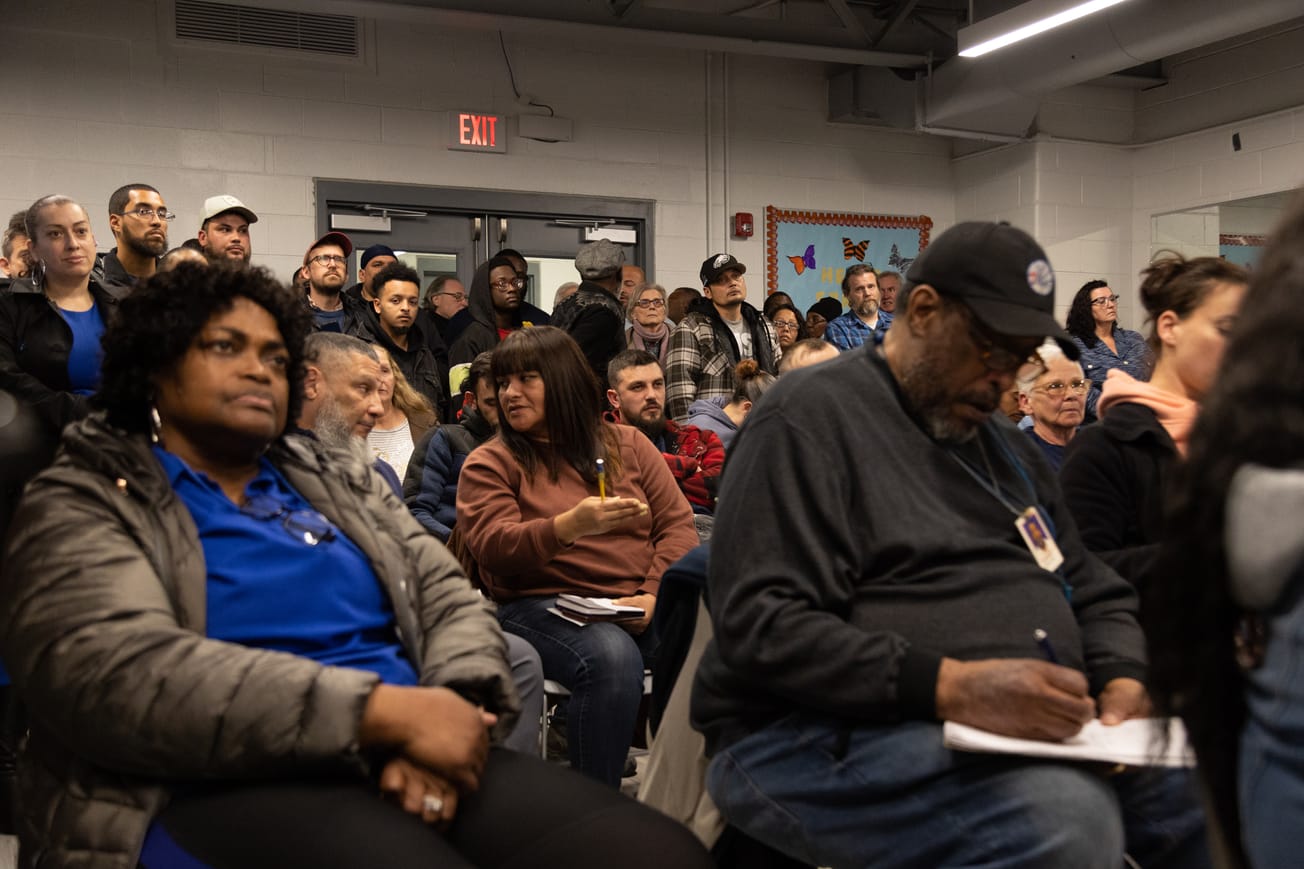

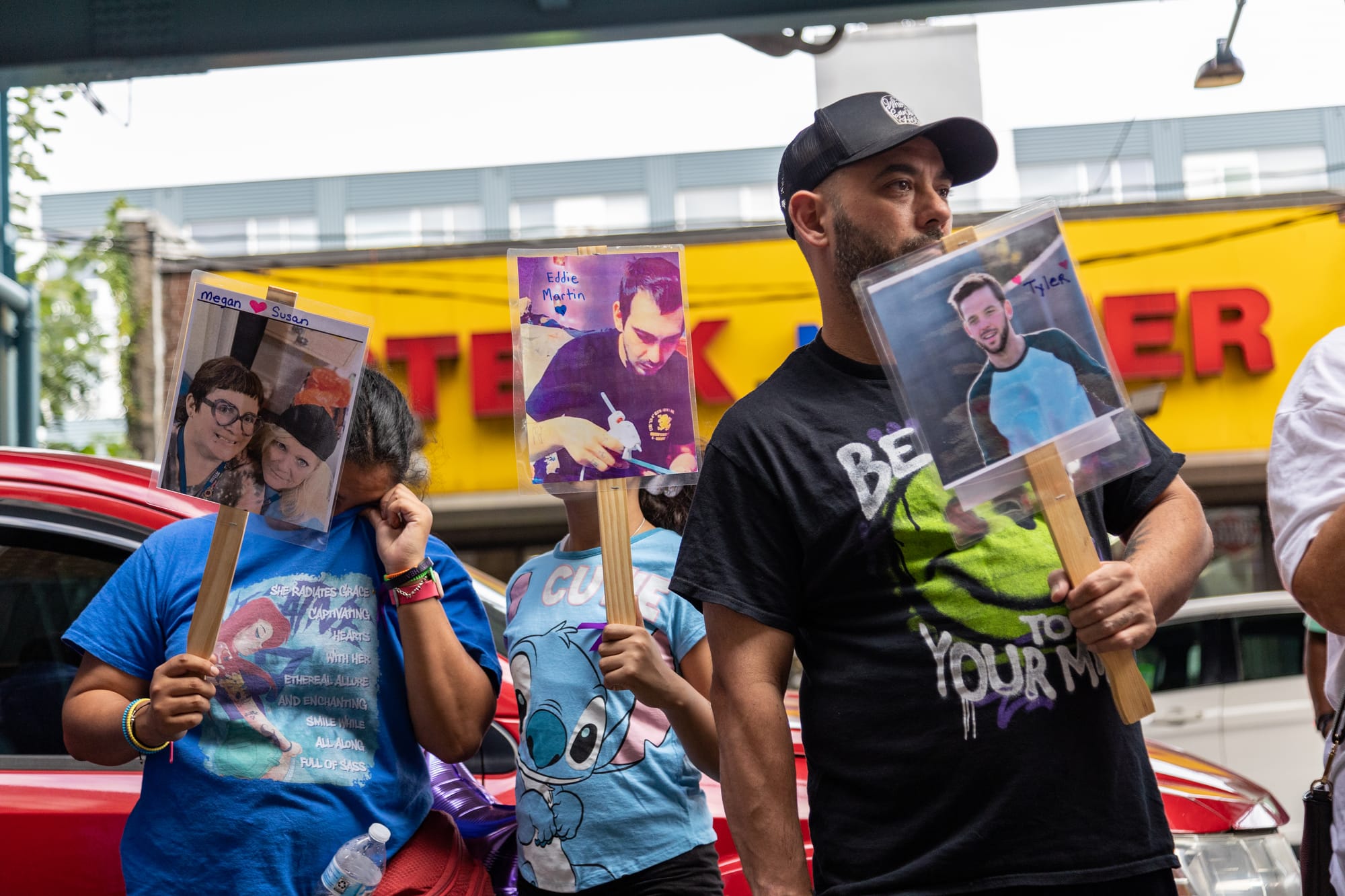

After police and volunteers carried their tables to the streets, the event continued on the steps of McPherson Square Library with a name reading for those who’ve died from overdoses. Organizers wrote the names on signs, and held a banner pinned with hundreds of purple ribbons. In the crowd, dozens of people held pictures of their friends and family members.

Kara Siegrist had a large photo of her late husband Michael Hill, which covered about half of her body. At the top of the photo she’d taped a sign reading “No Hope for Me” in tag lettering that Hill had drawn while he was alive.

He was an artist, Siegrist said, and he made the piece once while detoxing at home.

“One time when he didn’t want to go to rehab, he said, ‘Detox me in the bedroom, lock me in the bedroom,’” she said. “So I did, and I gave him his art supplies, and he slipped this out underneath the door.”

Siegrist and Hill lived in King of Prussia with their two children. But about six years ago, Hill “made his way down here in Kensington” while struggling with an addiction to fentanyl, she said.

“By coming down here over the years, getting him out, chasing him, looking for him, I got to see all the people around here and all the people who were helping people like my husband,” she said.

Hill died on February 5, 2023 at the age of 37. Siegrist has remained involved with a citywide harm reduction organization called Operation In My Backyard.

“I had to join and be part of the group because they saved my husband’s life a couple times,” she said. “Once you gain their trust, a lot of people are willing to go get help.”

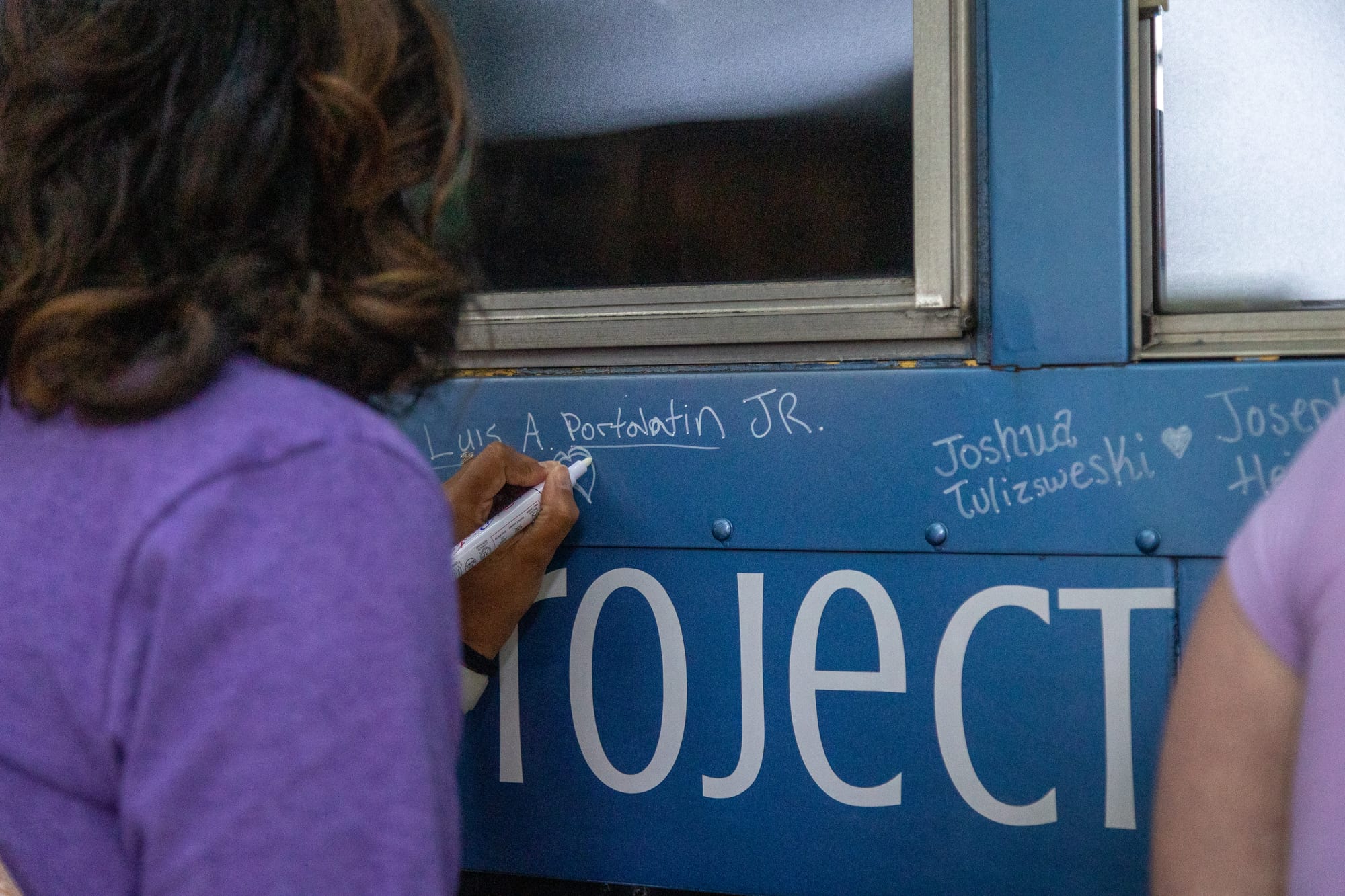

Event organizers invited attendees to write the names of lost loved ones on the outside of a memorial bus.

People could also visit artist Kathryn Pannepacker to be wrapped in a healing blanket.

Pannepacker also does art programming at Prevention Point, a health and social service organization in Kensington that has had to reduce the quantity of sterile needles it distributes because of new restrictions from the city. It’s also facing scrutiny around its provision of medical services.

“Harm reduction is so basic, it’s kindness, it’s just supporting people where they’re at,” Pannepacker said. “Everyone is somebody’s someone … just be kind to one another. Look at people in the eye. Ask them if they’re OK.”

Find resources for substance use help, including grief resources for loved ones, here.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.