This story was originally published by WHYY.

During the run-up to Philadelphia’s primary election last spring, all of the candidates for mayor, including Cherelle Parker and David Oh, promised to create a cabinet-level position — a department within City Hall — to oversee policies regarding arts and culture.

Leaders in the city’s arts sector are waiting to see if that will happen. Many are also urging the next mayor to use the arts not just a feel-good public amenity, but as a practical tool for governing.

Hal Real, CEO of the music venue World Cafe Live, is also the co-founder of the National Independent Venue Association (NIVA), which formed during the COVID-19 pandemic to create the Save Our Stages emergency funding act, which congress approved as the $15 billion Shuttered Venues Operators Grant Program.

He said the arts are an essential ingredient to human life. Even though “it’s the arts that really connect us at that human level,” that’s not how he lobbied for Save Our Stages.

“Did Save Our Stages have success because we made the argument about the arts connecting the world?” he asked. “Hell no.”

“We did it by talking to every district in this country, every congressman, every senator and their staff, and saying: ‘Do you think that your town, your village, your city can have a successful recovery if we’re all boarded up?’” Real said. “We’re the ones who put heads in beds. We’re the ones who put butts in seats at the bars and the restaurants.”

Real said World Cafe Live is on its way to recovering from pandemic shutdowns, with revenue about 90% of pre-pandemic levels.

The benefits of the arts sector go beyond economics. Under strong leadership from the mayor’s office, Real said the arts can be used to help with pressing city concerns.

“That leadership needs to recognize the value of the arts in Philadelphia. It’s greatly undervalued,” he said. “The ability of the arts to be a catalyst for the recovery of this city is huge. It’s huge in mitigating social justice issues. It’s huge in helping with gun violence.”

Neighborhood-based arts and culture programs have been shown to reduce crime, increase academic scores, and lower rates of child abuse, according to a 2017 study by the University of Pennsylvania’s Social Impact of the Arts Project.

The project spent two years comparing lower-income neighborhoods in New York City with cultural assets against those without. It found that arts and culture have a quantifiable, if indirect, positive effect.

“Culture doesn’t ’cause’ better health or less crime,” read the report summary. “Rather, cultural resources are integral to a neighborhood ecology that promotes social wellbeing.”

What can the arts do for the city?

Nasheli Ortiz González, the executive director of the Puerto Rican cultural organization Taller Puertorriqueño in the Fairhill neighborhood of North Philadelphia, said the tools to combat public safety and economic mobility already exist in neighborhoods. The next mayor needs to support them.

“The community understands what they need,” she said. “We have proven that organizations like Taller, like Providence Center, like Concilio, Congresso — our organizations understand the problem, understand how to create other paths for the Latinx community.”

Taller Puertorriqueño provides after-school programs and hosts public gatherings around cultural events to build community in the neighborhood, which is over 80% Latino with a 61% poverty rate.

Recently, Taller partnered with the Institute of Contemporary Art, on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania, to offer free bus service for residents of Fairhill to the ICA exhibition of work by David Antonio Cruz, a North Philly native who has become a successful artist.

González says that without a charter bus, many residents of North Philadelphia would not otherwise be able to witness the success of one of their native sons.

“Mobility is a big issue in all aspects: in transportation, in economics,” said González. “Those actions are stuff we need to see from the government. I want a bus so we can go to a gallery show and bring my youth. They need to see other ways of living.”

Just north of Taller Puertorriqueño, in the Franklinville neighborhood, the Esperanza Arts Center presents music, dance, theater, and cinema from Latin America and the Caribbean.

Its senior vice president, Bill Rhoads, said the question is not what the city can do for the arts, but rather what can the arts do for the city.

“The incoming administration faces a host of serious challenges in many areas, including gun violence, systemic poverty, and drug addiction — these issues are particularly prevalent in low income BIPOC communities,” said Rhoads in a statement. “Speaking on behalf of arts organizations that serve Black and brown communities, the next mayor needs to support and deploy creatives and arts institutions that work WITHIN these neighborhoods to affect real change.”

Another community nonprofit in another predominantly Latino neighborhood, Xiente in Norris Square, recently launched an economic mobility laboratory, to experiment with wealth-building initiatives that could lift low-income communities into the middle class.

González says the next mayoral administration could help these kinds of neighborhood initiatives by making it easier to receive help.

“We need the government to support us, instead of making permits, grants, anything so difficult,” she said. “As a nonprofit, that is the biggest value: time, and that the team doesn’t get exhausted. That is one of the things the government can start doing to support the work that we’re doing for them.”

The arts are not a ‘frill’

The new head of the Association for Public Art (aPA), Charlotte Cohen, agrees. She said one way City Hall can support the arts sector is to move the levers of government in its favor.

“I always say — and I spent a long time working in government — that a good bureaucrat is someone who knows how to get things done,” Cohen said. “There’s always bureaucracy. There are many, many layers to government entities, but knowing how to navigate around that will be very useful for anyone who’s looking to partner with a government entity.”

Before Cohen took the helm of aPA, she led the Percent for Art program in New York City, was a Fine Arts Officer for the U.S. General Services Administration in the New York region, and was executive director of the Brooklyn Arts Council.

New York has had a standalone Department of Department of Cultural Affairs, run by an appointed commissioner, since 1976. Cohen has witnessed first-hand the evolution of the relationship between New York’s arts sector and its government.

“When I was at One Percent for Art under Mayor Giuliani, I used to say that if we were One Percent for Opera he would have understood,” she said, noting Giuliani’s love of opera to the exclusion of other art forms.

“There was talk at that time at the end of his administration of abolishing the Department of Cultural Affairs and creating a sports and entertainment agency, which would have been not a good idea,” she said. “That was a low point.”

Under New York’s next mayor, Michael Bloomberg, Cohen saw an administration that actively engaged the Department of Cultural Affairs throughout his administration.

“It permeated everything. The department had a seat at every single table,” she said. “No matter what discussion: Department of Transportation, with the health department, Human Services, you name it — the Department of Education.”

While Bloomberg put a lot of attention on New York’s large, anchor cultural institutions, Cohen saw his successor, Bill de Blasio, spread support for the arts into outlying neighborhoods.

In Philadelphia, City Hall has an Office of Arts, Culture, and the Creative Economy that is not baked into the function of city government — it exists at the pleasure of the mayor. The city’s Cultural Fund distributes grants to the arts sector from a line item in the city budget, which can fluctuate wildly depending on the overall budget needs of any given year.

Cohen said arts in Philadelphia is not a “frill” whose funding should be sacrificed when more pressing matters arise around gun violence, public safety, and poverty.

“All these things should be and need to be priorities,” she said. “The arts can help intervene in public safety issues by diverting people from other activities, especially with younger children. Helping seniors in their isolation, that’s a real factor in aging people. I know the temptation is to just drop the arts, but it’s very, very hard to get back to the level it was at, when you take away money.”

‘A train wreck waiting to happen’

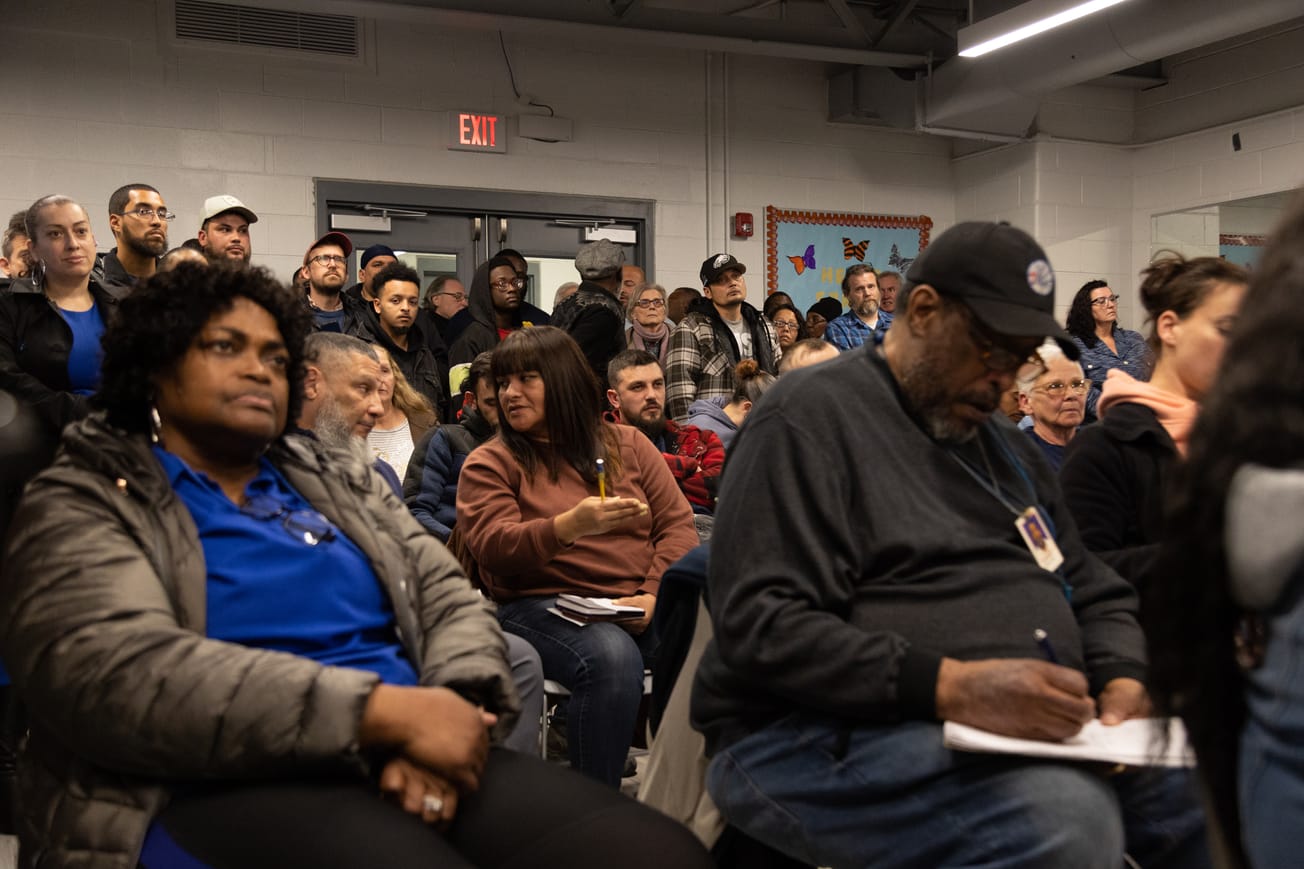

Cultural leaders acknowledge that the arts cannot act as a magic wand to make urban problems disappear; rather, they’re a tool to be utilized. Sabriaya Shipley, the new director of Theatre Philadelphia, had her eye on recent incidents of looting by young people when she said the arts should be part of a long-range plan.

“You have these situations of looting — I’m not saying it’s not catastrophic and not a big deal, it is,” she said. “But what’s even more of a big deal is that we assume there’s only one key point to what happened. In reality, it is always a train wreck waiting to happen, that we saw coming but no one reached out.”

Shipley said Theatre Philadelphia, which puts on the annual Barrymore Awards for excellence in local theater, will begin to use the Barrymores to recognize theater companies and individuals who excel in community engagement and education. This year’s Barrymore Awards ceremony will acknowledge outstanding community engagement, and in the future Shipley plans to offer an official award for that kind of service work.

The return on investment in the arts toward social justice and public safety, she said, takes patience.

“There’s a patience that comes with this position, or any position that is facilitating for the community. You have to have patience,” she said. “I say, patience with fire. There is a little fire that you light on people’s butts to get things done.”

The power of being present

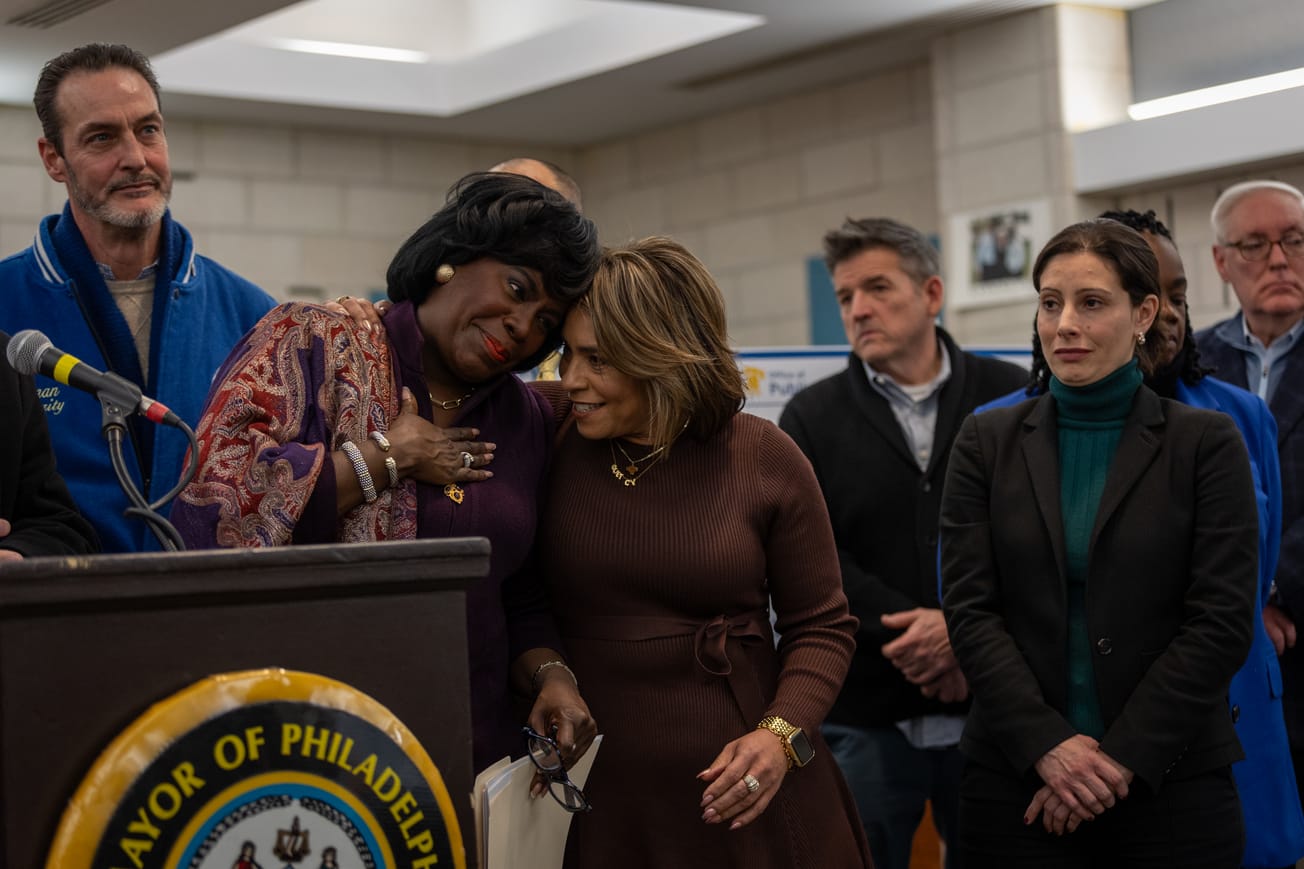

So what can the next mayor do?

First of all: Show up.

Several arts leaders expressed the need for the 100th mayor to be physically present at cultural events and arts organizations. Gonzalez of Taller Puertorriqueño has seen previous administrations that have been “checked out for a long time.” Charlotte Cohen suggested the next mayor appear at ribbon cuttings, in front-row seats, and use local arts as staging for public announcements.

“That just again signals an inclusiveness, and a mindset around the arts being an important factor in the lives of Philadelphians,” Cohen said.

The African American Museum in Philadelphia, the nation’s first African American museum funded by a municipality, has a close relationship with City Hall. Right now, AAMP is working with the city to relocate its museum to the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, to the former municipal Family Court Building complex.

Executive director Ashley Jordan hopes the next mayor will spend more time visiting the city’s cultural attractions.

“It is so important that they have site visits as part of their current working administration,” she said. “I feel like sometimes we can look at things on paper and we make cuts into that, but we never know the impact until we’ve been in the position of those who are impacted by those cuts. Sometimes some of our arts and culture sectors do not get the attention of the physical presence of some of our city officials.”

This story is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit www.everyvoice-everyvote.org. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.