This story was originally published by The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom covering gun violence in America. Sign up for its newsletters here.

Just before 9:30 p.m. on December 30, Philadelphia City Councilmember Jim Harrity was home watching TV when he heard a series of rapid bangs. As a longtime resident of the city’s Kensington neighborhood, which is notorious for street-corner drug dealing and its accompanying violence, he suspected it was gunfire.

Harrity looked out the window and saw a young man crumpled on the ground, so he jumped and yelled to his wife upstairs, telling her to get down and call the police.

“I see the kid laying there, then, all of a sudden, he sat up,” said Harrity, who was still rattled two weeks later.

“He had a phone in his hand, and I thought he was trying to call the police,” the at-large councilmember said. “I turned to go upstairs to my wife and as I turned, I heard them finish him off. They came back and shot him again.”

“It was right across the street from my house! It was one of the last murders of the year,” said Harrity.

He learned that the victim was 23. Police found a cellphone and a gun next to the victim’s body, and arrested two suspects that night.

While episodes like these still occur with some regularity in Philadelphia — and despite seeing death near his doorstep — Harrity believes that, overall, his neighborhood today is a much safer place than it has been in recent years. He hears less gunfire now, notices more police officers on patrol, and he sees city crime data that supports his belief.

Last year, the city saw a drop in gun violence so stark that it returned to pre-pandemic levels. The Philadelphia Police Department’s online data shows that homicides declined nearly 37 percent in 2024 compared to the previous year, the number of shooting victims dropped by nearly 35 percent, armed robberies committed with guns declined by 37 percent, and aggravated assaults with guns dropped by 15 percent.

In 2022, Harrity recalled, nearly 200 of the city’s 516 homicides took place in the three police districts that serve Kensington and nearby communities.

“Usually, when I would get home, the first thing that I would do is go upstairs, get my gun, and stick it next to me on the couch because my neighborhood was really bad for a long time,” Harrity said. “But it’s been so quiet for the last few months.”

“I haven’t had drug dealers on my corner for about two months. So for the last two weeks I didn’t even bother to go up to get my gun after getting home. It’s been very nice,” he said. “The kids have been out playing.”

“It’s not enough”

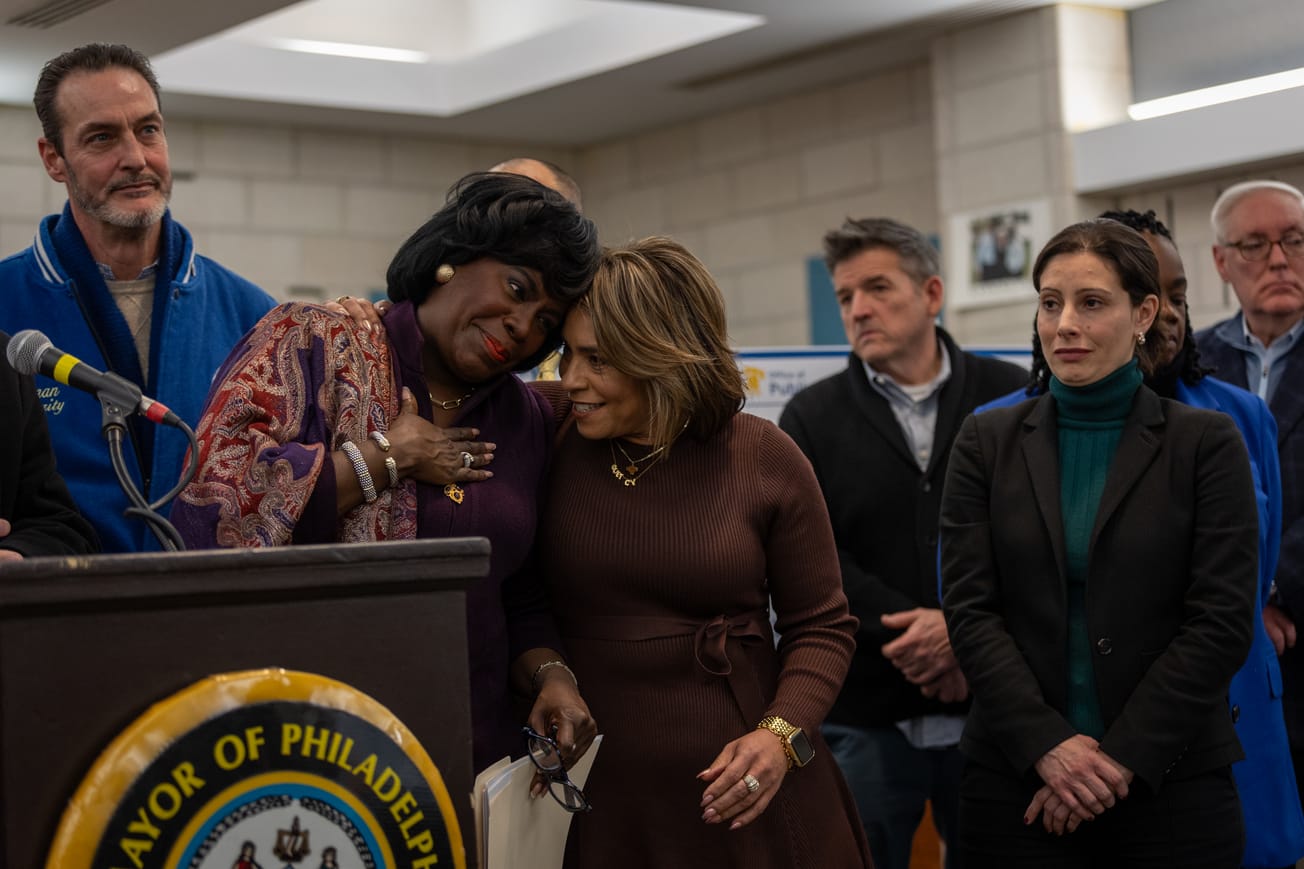

In her first State of the City address in late December, Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker trumpeted the fact that a recent Center for American Progress report found that, while violent crime dropped in big cities across the country in 2024, Philadelphia saw the steepest rate of decline.

“Let me be very clear about something: It is not enough! The numbers don’t mean a damn thing,” said Parker, who took office last January after campaigning to make Philadelphia the safest, greenest, and cleanest big city in the country.

“We cannot and will not rest until every neighbor in every neighborhood feels safe in their homes and on their front steps,” she said. “Until every child can walk to school safely, until every senior can sit on their porch on a summer night and feel safe again.”

Though it’s too soon to know exactly what drove gun violence down, Parker credited her law enforcement team’s 2024 public safety plan. Since then, more than 200 police officers have been dispatched to the highest-crime areas, $28 million has been awarded to dozens of grassroots community violence interruption initiatives, and city-run violence prevention programs continued their missions.

Among them is Pushing Progress Philly, which launched in the summer of 2023 to serve adults in neighborhoods most vulnerable to gun violence, and Group Violence Intervention, which launched in 2020. In 2024, GVI helped 480 people, a 36 percent increase from 2023, according to the Chief Public Safety Director’s Office. A federal grant helped the city start a companion GVI program serving juveniles in September.

Throughout the new year, city officials will be paying close attention to which of their crime-fighting initiatives are working and which are not, said Chief Public Safety Director Adam Geer.

“If it’s working well can we scale it up? If it’s not working well do we have to make any tweaks to it?” he said. “It’s really just being at the cutting edge, at the tip of the spear of what is working in violence prevention, then get it done.”

Key to the city’s success last year, Geer said, was Police Commissioner Keven Bethel’s plan of pinpoint enforcement, which led to more arrests, the continued work of grassroots violence interrupter groups, and the city’s Office of Reentry Partnerships, which help smooth the transition for those coming out of incarceration.

“It’s a convergence of a lot of hard work, in a lot of different lanes, all getting behind the same side of the ball and pushing it forward,” Geer said.

“100 percent different”

Pastor Buddy Osborn’s Kensington-based Rock Ministries, which provides a mix of Bible study and combat sports training for youth, also stepped up its efforts to help those addicted to drugs get into detox treatment — close to 500 people, he estimates. Such efforts, he added, have also helped the city tamp down crime.

Osborn had just come from a ceremony that Parker held to celebrate the January opening of Riverview Wellness Village, a $100 million, 340-bed city-run recovery housing facility for people finishing treatment for substance use disorder.

“Things are 100 percent different. We’re ground level with what’s going on,” he said. “And it starts at the top, and the top is the mayor. She’s leading out front.”

Osborn praised Parker’s compassion.

“Look, a single mom raising a child,” he said. “She understands the whole concept of community, and I think that’s a blessing.”

Harrity, the Kensington councilmember, says multiple factors drove the decline in violence.

“The last administration tried to go another way. It did not work. We are moving forward in a new direction,” he said, echoing Parker. “The criminals out there know that this free-reign thing is over. The city’s a different place. Council people are different, the police commissioner is different, the mayor is definitely different. We’ve learned from a few mistakes that we’ve made in the past, and we’re about it now.”

In addition, Harrity said, the increase in city and privately owned cameras is helping law enforcement track down more shooters to take off the streets. The shooting in front of his house is a textbook example. Police used surveillance video to track the two suspects to an abandoned house a block away, where they had broken a window and attempted to hide. The suspects were apprehended after trying to flee through the back door.

City Councilmember Mark Squilla’s First District stretches from South Philly, through Center City, up into Kensington. He, too, says his 160,000 constituents felt the effect of Philadelphia’s crime-fighting in 2024.

“We’re hearing that they’re starting to feel like it’s getting safer,” Squilla said. “I see that the feeling’s there, but it's going to take time to change the perception part. But that will come through consistency, through years of decline.”

“Not only declines in homicides and violent crime, but decline in retail theft, and breaking into cars, and stealing tires,” he said. “Once you start seeing more and more of those declines, you’re going to have that feeling of safety throughout the city of Philadelphia.”

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.