Amanda Cahill, of Roxborough, died in a Philadelphia jail Saturday morning after police arrested her for drug possession in Kensington three days earlier.

Cahill, a mother of two sons, was one of 34 people arrested for narcotics violations and outstanding warrants in a coordinated police sweep under Mayor Cherelle Parker’s Kensington initiative. The Philadelphia Police Department’s East Division targeted G Street and the Kensington and Allegheny corridors on Wednesday.

The medical examiner has not yet released her cause of death.

Jessica Yard, Cahill’s aunt, wrote in a statement to Kensington Voice that Cahill lived in Roxborough but had been visiting Kensington to use drugs for the last decade or so.

Cahill was funny and outgoing, Yard said, and was striving to overcome addiction so she could be present for her kids.

“Amanda loved her boys. She wanted nothing more but to be there for them, to be healthy for them,” Yard wrote. “She fought hard.”

“I used to pray Amanda would be picked up, thinking she’d be safer in jail than on the streets. That at least we knew she’d be safe. Sadly this wasn’t the case.”

As far as the family knows, Cahill wasn’t taken to a hospital before being detained in jail, Yard said. The family still doesn’t know the cause of death.

“We were called and told that she was gone,” she said. “All they knew was that she was dead, and we could get her Monday.

She said people living with addiction should be able to get treatment, not “left to die alone in a jail cell.”

“We want these people to have a fighting chance and to live the life they were supposed to live,” she said. “The jails need to be better equipped. These people need to be helped. They’re sick. “

Several advocacy groups shared the news of Cahill’s death on social media, blaming Parker, her administration, and the Kensington Caucus – a group of four City Council members who introduced the concept of “triage centers,” which would force people to choose between addiction treatment or jail.

“The truth is that Amanda Cahill died in a cell as a direct result of a cold-blooded policy enacted by @phillymayor, the Parker administration, @councilmemberquetcy @cmmarksquilla @councilmembermikedriscoll and @councilman_jimharrity,” wrote South Philly Food Not Bombs on Instagram. “There's a word for the willful disregard of people's lives and it isn't public service.”

The Mayor’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

“The only way police and incarceration stop drug use is by killing people,” posted the Community Action Relief Project (CARP) on Instagram. “As we grieve the loss of Amanda Cahill and send love to her family and friends, we demand an end to the carceral system responsible for taking her life and the lives of dozens more people who use drugs in Philadelphia since 2018.”

Since 2018, at least 26 people have died in Philadelphia’s jails from drug-related incidents, according to a Philadelphia Inquirer analysis.

Harm reductionists, health experts, and prison accountability advocates have long warned about the dangers of using policing and incarceration as solutions to the city’s addiction and overdose crisis. They have called for sustainable solutions, including better access to adequate medical care, and low-barrier trauma-informed addiction treatment and housing.

Police and city sanitation workers have led Parker’s initiative in Kensington, where they have targeted high-visibility areas like Kensington and Allegheny avenues and less visible ones like the underpasses of I-95.

'Horrendous' conditions

Philadelphia’s prison system has been chronically understaffed and has struggled to provide adequate health care.

Those closest to the prison system – including former Prisons Commissioner Blanche Carney, who retired in March – have warned that Philly jails are over capacity.

Philadelphia Police Commissioner Kevin Bethel also said he would not “force 1,000 people” into prison knowing the prison system “can’t take it.”

In August, a federal judge ordered Philadelphia to pay $25 million and address staffing shortages at the city’s jails. The judge found the city was violating its 2022 settlement agreement after a class-action lawsuit filed in 2020 over "horrendous" conditions.

The Pennsylvania Prison Society has captured many of these concerns in the quarterly reports the organization publishes about the prison system’s climate.

“We hear regularly from individuals in the prisons about having to wait weeks and even months for medical care,” said Noah Barth, who oversees prison monitoring for the Pennsylvania Prison Society. “So further straining that system through increased admissions is just a recipe for dysfunction and preventable harm.”

Barth expressed similar concerns about incarcerating people with substance use disorder during a May City Council hearing organized by the Committee on Public Health and Human Services.

“They're beleaguered,” Barth said. “They don't have enough personnel to run operations.”

That means “attending to basic functions,” like getting people out of their cells on time and getting people to medical appointments, but also includes “routine medical care” like treating infections and wounds.

During a May interview with Kensington Voice, Bruce Herdman, the prison system’s chief medical officer, cautioned that due to the officer shortage and prison policies, it is difficult to deliver timely, high-quality care.

While Philadelphia offers higher levels of addiction care than most other Pennsylvania counties, the intake process can take many hours, if not days. And there is a documented backlog in assessment appointments for people who want to get medication for opioid use disorder, largely because there aren’t enough corrections officers to escort people from their cells to the medical unit.

“We have a whole bunch of standards that we're not meeting – it's very frustrating,” Herdman said. “There's no easy answer to this security shortage at the moment … we don’t have enough, and we don’t have a choice.”

‘It’s a tragic situation’

In January, Councilmember Quetcy Lozada (District 7) told Kensington Voice that she believed the prison system could handle an influx of people, despite a 50% corrections officer vacancy rate that Herdman said has persisted since 2020.

“Do they have the capacity to be able to bring these folks in if we were to do something on a large scale where we pick people up? Can our prison systems handle that right now?” Lozada said. “And the answer is yes.”

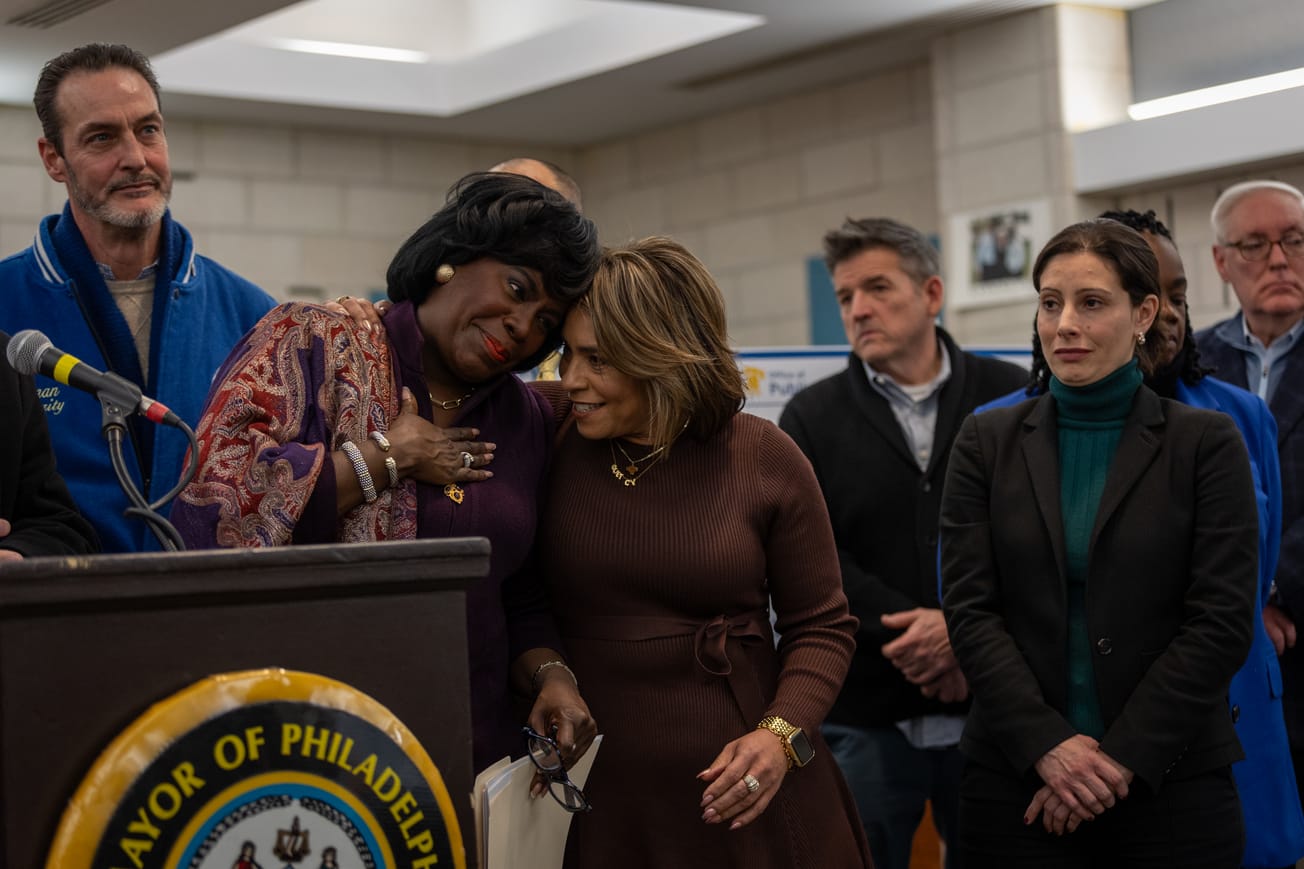

On Monday, Lozada gave her “sincere condolences” to Cahill’s friends and family in a written statement.

“The goal of our city’s effort in Kensington is to restore lives, so it brings me great sorrow to see hers cut short,” she wrote. “As a city, we must continue working with urgency to bolster the wellness ecosystem that increases access to necessary care and intervention when they need it.”

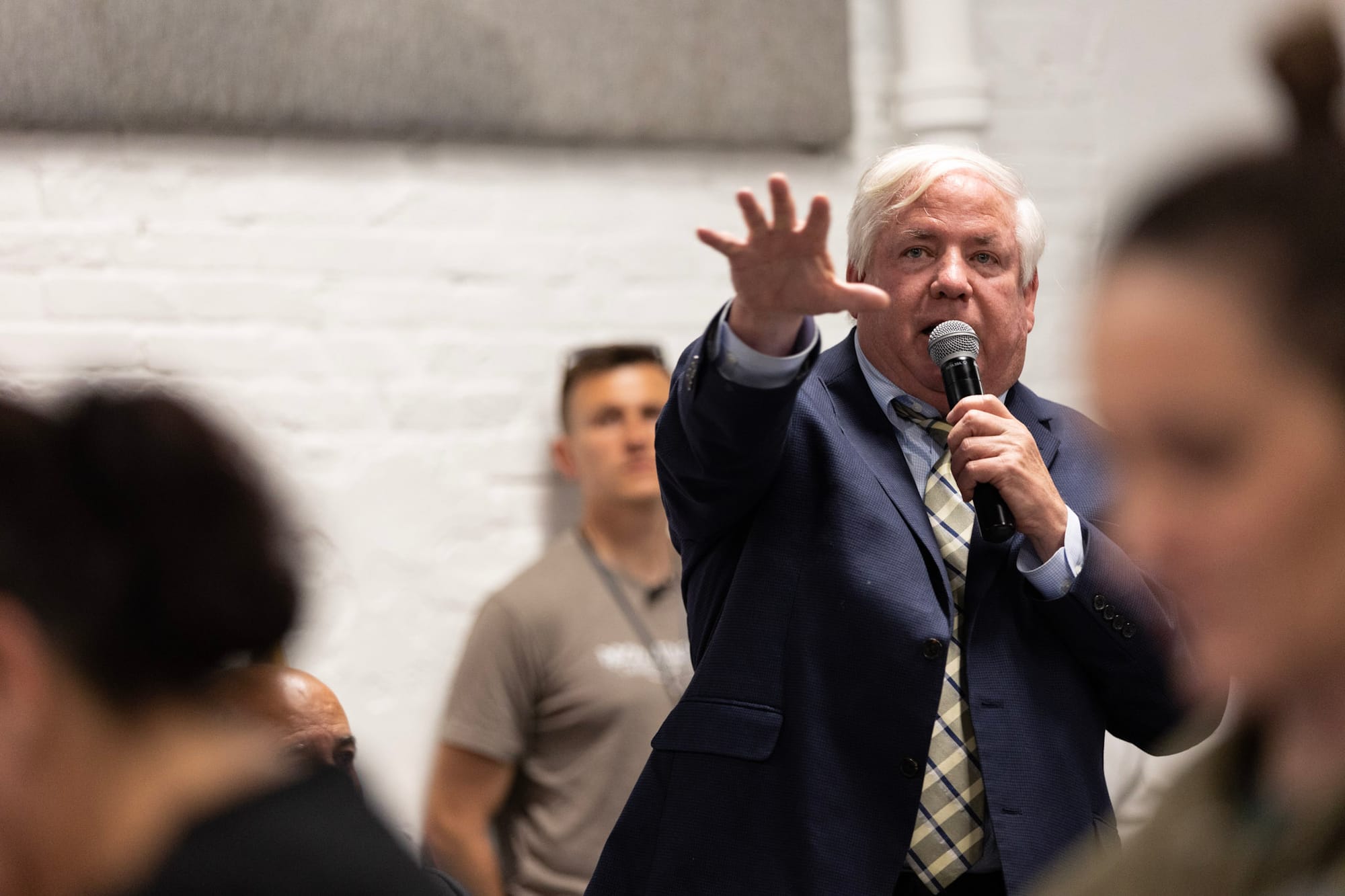

In an interview on Monday, at-large Councilmember Jim Harrity pointed to a planned drug treatment facility on State Road, which is supposed to be built over the next three years with $100 million in city funding.

“It’s a tragic situation,” said Harrity, a member of the Kensington Caucus. “This is the reason we’re trying to look at all avenues. Hopefully, this will be a learning experience for the city, and we can get more of these people not in jail but in physical rehab.”

Previously, Harrity testified in support of prison as a treatment option.

“As somebody in recovery, I just want people to know that some of us don’t go willingly,” Harrity said at a February council hearing. “Some of us get recovery because we get sent to jail or we get mandatory into a rehab.”

Council members Mark Squilla (District 1) and Mike Driscoll (District 6) – the other two members of the Kensington Caucus – did not respond to requests for comment in time for publication.

But other council members are pushing back against their colleagues.

On Monday, at-large Councilmember Nicolas O’Rourke said said considering the municipal and federal courts that have deemed Philly’s prisons as unsafe “for years now, the death of Amanda Cahill was utterly, unacceptably predictable.”

“Only a couple of months into law enforcement’s activation in the Mayor’s plan for Kensington, Ms. Cahill’s death should cause our city to reconsider what achieves actual public safety, genuine wellness, and dignity in treatment — yes, even for those with open warrants,” O’Rourke said.

At-large Councilmember Kendra Brooks said that she has warned for years that “criminalizing drug use does not work.”

“It didn’t work during the War on Drugs, and it won’t work now,” Brooks said Monday. “During budget negotiations with the administration, I repeatedly raised questions about whether our jails could handle a surge of medically fragile patients, and it’s clear from last night’s news that the answer is no.”

‘A chorus of many voices raising concern’

The Pennsylvania Prison Society has been “one amongst a chorus of many voices raising concern about a police-focused response to what is a treatment issue,” said Barth, who spoke to city council in May.

“While it is a tragic outcome, unfortunately, it does not come as a surprise to many people who have consistently been warning the city that a tragedy like this was likely to occur,” Barth said Monday.

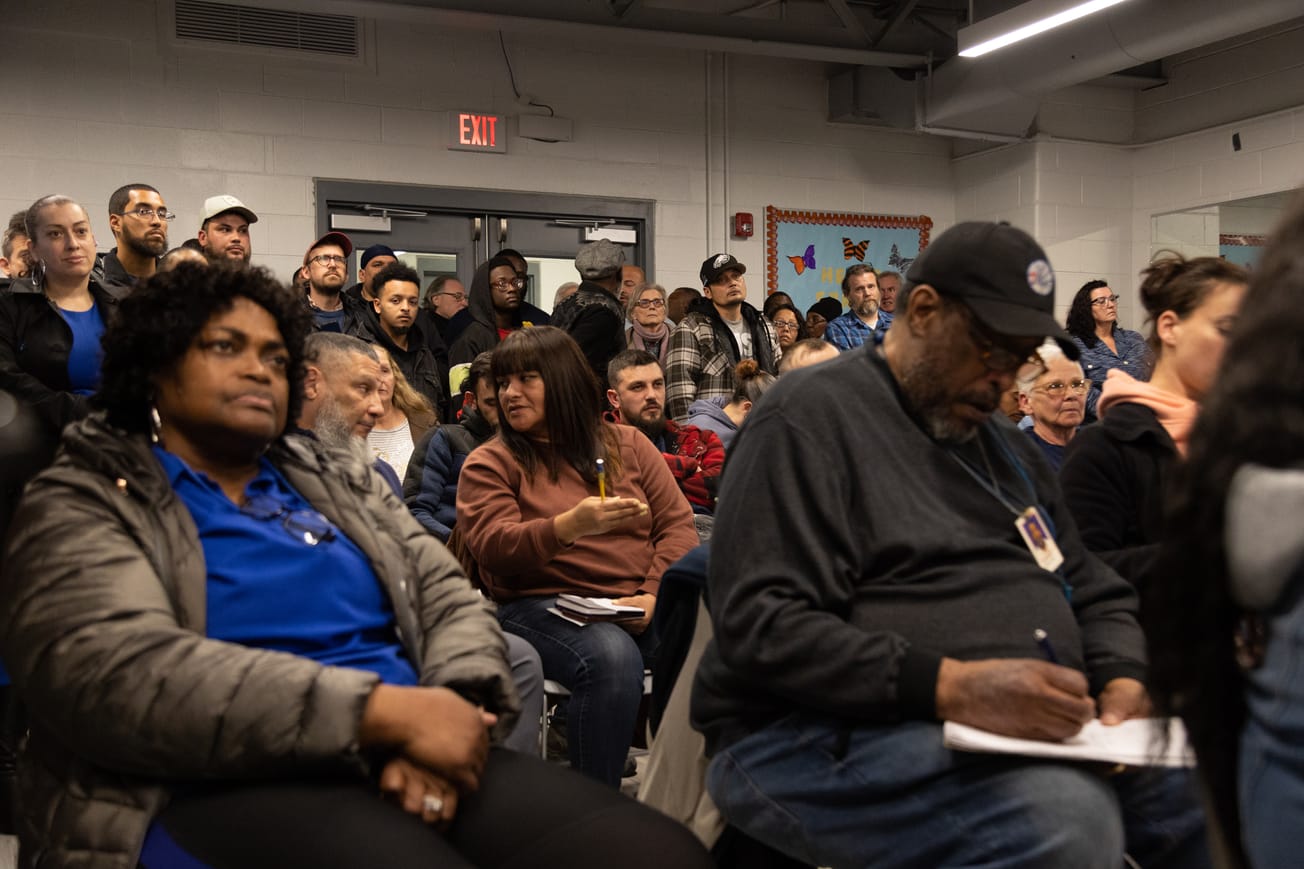

In March, about 70 people rallied outside of City Hall in opposition to a wave of new policies and initiatives, ranging from the Kensington Caucus’s “triage” system idea to the Parker administration’s harm reduction crackdowns to business curfews for Kensington.

“I think they’re trying to kill everybody,” said Kara Siegrist, a volunteer with Operation in My Backyard (OPIMBY), whose husband spent six years in and out of jail and rehab before dying in Kensington in February, 2023. “Putting them into jails is not a solution … I don’t understand why they want to kill our family.”

Last week, advocates returned to City Hall to testify against Lozada’s bill banning mobile care services in most of Kensington.

“Over the past year, myself and my colleagues have distributed numerous studies to your staff, taken meetings with you,” said Kelsey León, a clinical researcher, a volunteer with CARP, and a member of the Coalition for Dignity and Treatment. “We’ve provided public comment at City Council sessions and provided evidence that at a macro, micro level, harm reduction saves lives.”

Rachel Santiago, who was previously incarcerated at the Philadelphia Industrial Correctional Center (PICC), where Cahill died, now advocates for conditions in women’s jails with the Still We Rise Freedom Coalition. In a statement on Monday, Santiago called Cahill’s death “entirely predictable and preventable.”

“The PDP is simply not capable of making sure people in custody are safe and healthy,” Santiago wrote in the statement. “The dozens of other women with serious medical needs, from pregnancy complications to heart conditions, who are still locked up should be brought home immediately so they can receive the care they need.”

This month marks one year since Philadelphia City Council voted to ban supervised injection sites in all but one city district.

In September 2023, Kensington resident Moses Santana testified against Lozada’s legislation introducing the ban.

“If you folks deny this tool, you are responsible for these deaths,” Santana said. “I hope that each and every one of you who vote yes to the ban comes to every funeral.”

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com.